|

In connection with the anticipated opening of a new Essex County Jail in Lewis, N. Y., during the summer of 2007, the New York Correction History Society (NYCHS) created this "virtual tour" of pre-computer record keeping at the county's old jail in Elizabethtown.

IN JAIL BOOK: ENTRIES FOR 3 OF ESSEX COUNTY'S 4 CAPITAL CASE EXECUTIONS

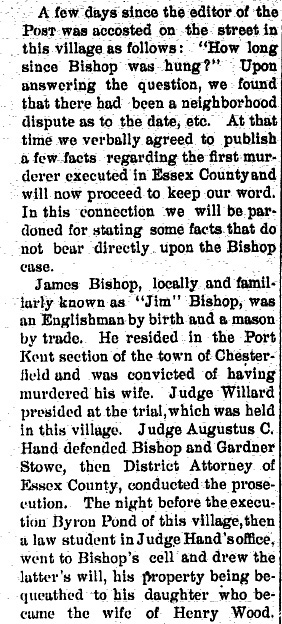

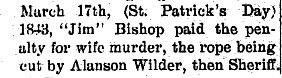

Above are four separate images of excerpts from a column appearing in The Elizabethtown Post May 3, 1900.

|

Three of four executions arising from Essex County capital murder cases involved inmates recorded in the ledger (left) entitled Record of Commitments to Essex County Jail. Its entries span 45 years, from the late 19th Century into the early 20th Century. They begin June 26, 1879 and end June 28, 1924.

The first of the four executions arising from Essex County capital murder cases took place at the Elizabeth jail March 17, 1843 -- more than 36 years before the above particular ledger's first inmate entry.

Forty years separated Essex County's first rope execution (James Bishop, 1843) and its second (Henry D. Debosnys, 1883). Thirty-five years separated that hanging and third and fourth executions resulting from an Essex County capital murder case (John Kushnieruk and Stephen Lischuk, 1918, in Sing Sing's electric chair).

1ST OF FOUR EXECUTED: JIM BISHOP

Decades after that first hanging -- of "Jim" Bishop for the murder of his wife -- local newspapers occasionally published accounts recalling the case, but with scant few details about the actual violence inflicted on her. At least, those that happen to be available on the Internet focus primarily on the execution itself.

However, along with extensive positing and interpreting of perceived broad social and historical patterns, considerable factual detail concerning the Bishop case can be mined from Dr. Sean T. Moore's "Justifiable Provocation: Violence Against Women in Essex County, New York; 1799-1860."

The article appears in the

Journal of Social History (V. 35.4 June 22, 2002, pages 889-918).

Moore is now an adjunct lecturer in history at SUNY Plattsburgh.

In his carefully researched and well annotated essay, he gave several specific examples showing how trial prosecution testimony established that Mrs. Bishop had been repeatedly subjected to physical abuse by her husband and that her death was only the last of a series of brutal beatings of her by him.

Even though the 1879 - 1924 ledger came long after the Bishop's trial and execution,

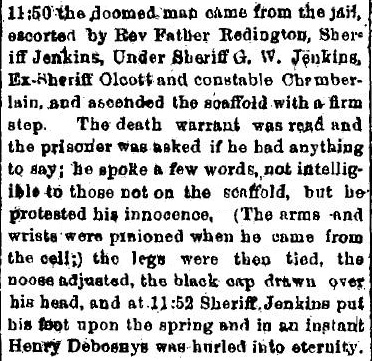

Above are three separate images of excerpts from a column appearing in The Elizabethtown Post Feb. 4, 1904.

|

this web page on the trials and executions of three Essex County jail inmates who did come within the ledger time span would be remiss not to consider the county's first execution.

Here are some James Bishop case excepts from Dr. Moore's article, except here the trial-related text is presented before the execution-related text, reversing their arrangement in the original:

". . . . William Hayes, James Bishop's nearest neighbor, reported on the night of the murder November 12, 1842 that he 'heard a noise in the house after I got a few yards by stopped [and] supposed he was whipping his wife, but hearing no more noise went on.'

"Hayes stated that Bishop 'bruised her up once before so badly that I did not think she would live twenty four hours.' "Hester suffered violence for at least a full year prior to the murder; in this period, the couple shared a house with James's brother, John and his wife.

"Clara Bishop described her brother-in-law as a harsh man and recalled 'his slapping her [Hester] on the head until her nose & mouth bled considerably and she complained of his hurting her head.'

"Hester tried three times to leave her husband, first on August 20, by boarding a sloop on Lake Champlain and disappearing for 10 days, and the last time, weeks before her death.

"In each case, James searched her out and forced her to return home.

"Sarah Brooks, who lived in the Hayes's household, remembered seeing Hester the day she returned from the town of Essex, running out of her house naked and covered with blood.

"When she saw Hester later that day, Brooks told the prosecuting attorney 'her [Hester's] eyes were all beat up as big as your fist, and her lips badly swollen.'

"Although the violence committed against Hester was common knowledge, no one reported it to the authorities.

"Men such as William Hayes were usually reluctant to physically intervene in cases involving domestic disputes. . . .

"Two days after the murder James appeared before the Chesterfield Justice of the Peace to answer the charge of murder.

"He testified that Hester had been sick all day and fell three separate times that evening, once while fetching water at the brook, a second time in the house when she 'struck her face against the light stand,' and a final time when she fell 'backward in the cellar way.'

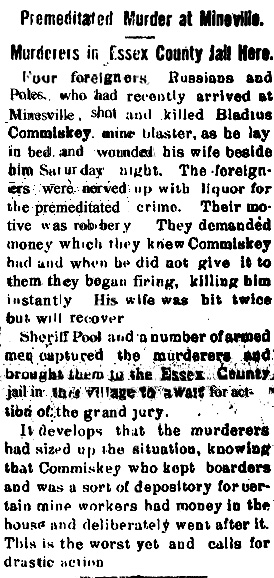

Above are two separate images of excerpts from a column appearing in The Essex County Republican May 24, 1968.

|

"James's explanation that Hester's illness caused her to faint and fall and that she 'appeared delirious,' failed to convince the Justice of the Peace. The severe injuries to Hester's face and head and the 75 to 100 bruises found on her body supported the charge that James clubbed Hester to death down by the brook. "While the prosecutors did challenge James Bishop's description of Hester's death as accidental, neither lawyer set out to contest whether James Bishop cruelly beat or mentally abused his wife throughout the duration of their marriage. . . .

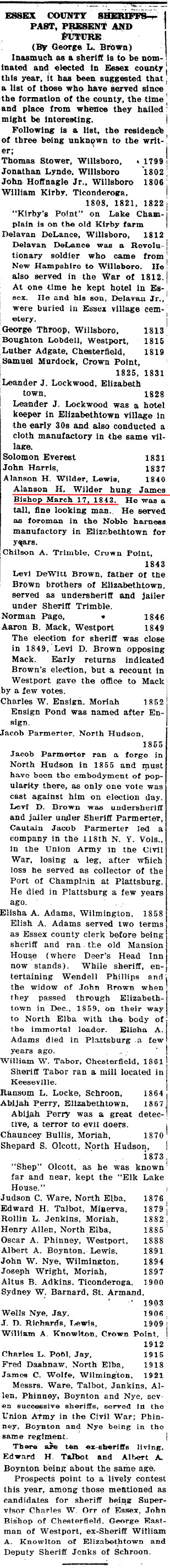

Above is an image of George L. Brown's listing of Essex County sheriffs that appeared in the Ticonderoga Sentinel in early 1924. Red underline added to image for emphasis.

|

"James Bishop's lawyers presented Hester as a woman who neglected her wifely duties and thus was complicit in her own death. . . .

"The three female witnesses pointed out that if Hester failed in her duties as a wife, and mother, the fault belonged to James Bishop. "They claimed that James deprived his wife and child of the proper food, protection, and clothing. . . .

"Both Bishop's status as a relative outsider to the Chesterfield community and the extreme nature of his violence against Hester contributed to the jury's returning a guilty verdict after only twenty minutes of deliberation.

"The two witnesses called by the defense offered very little testimony and barely knew Bishop. "Also, the fact that the Bishops had moved three times in the preceding two years suggested that they were a rootless couple. . . .

"Four months after brutally murdering his wife, James Bishop mounted the newly-constructed wooden platform in the center of the Elizabethtown prison yard in Essex County.

"Displaying all the attributes of the repentant sinner, he climbed the four short steps to the gallows. "Nervous and trembling and flanked by the sheriff and two clergymen, Bishop attempted to read a passage from the Bible.

"Almost fainting and unable to gain his composure, he directed a clergyman to read the sixth chapter of Proverbs warning against the evils of folly and adultery. "With the conclusion of the scriptural readings, Bishop regained his poise and spoke in a calm, clear voice to the audience of county officials, clergymen, and newspaper reporters.

"A local newspaper recounted Bishop's scaffold speech delivered in the shadow of the 14-foot-high cross beams.

"'He cautioned young men setting out into the world to 'shun bad company and vile associations.'

"He further 'advised and urged all men to be governed by principles of honor and integrity, and ladies to be true to their vows.'"

"As a final request, Bishop asked that his 2-year old daughter Polly be 'taught the principles of virtue and Christianity, and directed honestly and guided safely through all the winding passages of the world.'

"With these final words Bishop 'took a last leave of the Sheriff, the Clergymen, and Physicians, kissing them all in a very affectionate manner.'

"At exactly one minute past three o'clock in the afternoon on the 17th day of March 1843, the executioner chopped the rope holding the 200 pounds of counterweights and Bishop, with a handkerchief clutched in his hand, was propelled swiftly into the air.

"Within a minute and a half Bishop let go of the handkerchief as his body violently convulsed in a hopeless struggle with the hangman's noose. "In the space of three minutes, his body hung lifeless and motionless in the cool Adirondack afternoon air.

"The Essex County Times And Westport Herald regretfully noted that James Bishop was the first person executed in Essex County, New York, since its formation in 1799, stating 'God grant it may be the last.'"

Unfortunately, it was not the last case of a capital murder and hanging execution in Essex County.

Another -- also involving a wife killer -- would occur 40 years later.

JOURNALIST/HISTORIAN:

GEORGE L. BROWN

Yet for local journalist/historian George L. Brown, the Bishop case apparently had a stronger hold.

In his listing of Essex County sheriffs from 1799 through 1921 (see image above), Brown mentions only Sheriff Alanson H. Wilder in connection with an Essex execution (Bishop's) even though Sheriff Rollin L. Jenkins presided in 1883 at the county's second rope execution (that of Henry Debosnys ) and even though Sheriff Charles L. Pool was involved in sending two killer-robbers to Sing Sing's electric chair in 1918 (John Kushnieruk and Stephen Lischuk).

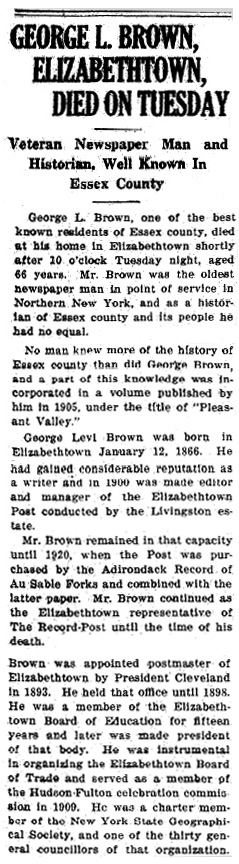

Above is an image of excerpts from the Adirondack Record - Elizabethtown Post Aug. 18, 1832 front page story on the death two days earlier of journalist/ history George L. Brown. in early 1924.

|

Brown's noting Sheriff Wilder's connection to the Bishop rope execution but not Sheriff Jenkins' tie to the Debosnys rope exeuction nor Sheriff Pool's link to the electrocutions of Kushnieruk and Lischuk is particularly interesting when one considers that the future editor/historian was born 23 years after the first hanging.

Brown was 17 at the time of the second hanging and 52 at the time of the two electrocutions.

As noted in the Adirondack Record - Elizabethtown Post 1932 front page story on Brown's death (right), he became editor of the Post in 1900.

Among his earliest columns as editor was the one whose image appears at the top of this web page ("A Few Notes in Connection With the Trial and Execution of 'Jim' Bishop," May 3, 1900).

In drawing up his sheriff's list in 1924 at age 58, perhaps Brown had better recall of his early historical research as Post editor into the 1843 hanging than any work he did on the executions that took place during his own lifetime.

About a year after his 1900 column on the Bishop hanging, Brown used the 18th anniverary of the newspaper's "Friday run" of the Debosnys' hanging as an occasion for a column about Essex County's second (and last) rope execution.

2ND OF FOUR EXECUTED:

HENRY D. DEBOSNYS

The "Friday run" story summarized the crime, the arrest, the trial, the sentence, the post-sentence efforts at appeal and commutation, and then added details about the Friday late morning execution:

"Henry Delactnack Debosnys (so called) was arrested August 1st, 1882. at Essex

village, in Essex County, for the murder

of his wife, Betsy Wells.

"He was married to Betsy Wells, a widow owning

and living upon a small farm near what

is called Whallon's Bay, on Lake Champlain, in the town of Essex.

Above is an image of the opening paragraphs of George L. Brown's April 25, 1901 Elizabethtown Post column recalling "the Friday run" of the newspaper account of the Debosnys hanging 18 years earlier. The phrase "the Friday run" refers to the issue dated Thursday, April 26, 1883 but actually published the next day shortly after the hanging. Below is an image of the opening paragraph of the 1883 story explaining the Friday publication of the Thursday-dated newspaper.

|

"The day before the murder he was seen

going toward Westport with his wife.

"The

following day he was seen by parties near

Westport returniug with his wife; but

when within about two miles of his home,

and near the residence of William Blinn

he was seen by Mr. Talbot, a highly respected farmer of Essex, skulking in a piece of wood; afterward, a few minutes,

he passed Mr. Blinn’s house in a buggy

alone.

"Mr. Talbot’s suspicious were aroused, and he

at once communicated with his

neighbor Mr. Blinn, when together they

went to the woods and commenced a search.

"Not many minutes after they found a trail,

having appearance of something having been dragged through the leaves and

grass; following this trail tbey soon found

the body of Betsey Wells, very adroitly

covered with leaves amid bushes.

"An examination showed a deep stab in the throat

and two bullet holes in head.

An alarm

was at once made, a messenger sent to

Whallonsburgh, the nearest telegraph station, and within five hours from the time

Mr. Talbot's suspicions were first aroused

by seeing the murderer drive

away alone,

Debosnys was arrested at Essex Village,

in the Post Office, while giving directions

about letters that might arrive for his wife.

"On his person and in his wagon were

found clothing, identified as havimg belonged to his wife, together with jewelry,

etc., and a revolver with two ohambers

empty, (the bullets corresponding with

those found in the head), and a single

bladed knife with blood upon it.

"At the Circuit Court heId in December

an indictment for murder was found

by the Grand Jury, and the trial was set

down for March 6th at a Special term,

Judge Landon presiding."

"The trial occupied less than two days time; the jury

were absent from the Court room but 8 minutes and returned with their verdict of murder in the first degree. He was sentenced to be hanged April 27, 1883."

�

Below is an image of the name, commitment date, and charge entered for Henry Debosnys in the Elizabethtown jail ledger. The entry spells the last name "De Bosnys" (inserting a space after "De" and capitalizing the "B").

But this web page adopts the "Debosnys" spelling employed by editor/ historian Brown and most newspapers of the period. The date is entered as "2" preceded by a ditto symbol that refers back to August as the month. Although arrested and jailed August 1st only hours after the slaying, he was first held in the Westport Town lock-up and then brought to the county jail the next day. The charge entered was "Murder."

Left is an image of the age, country of origin, and marital status entered for Henry Debosnys in the Elizabethtown jail ledger: respectively, "46," "Portugal" and "Married." The latter entry was, technically speaking, incorrect. "Widowed" would have been more accurate, if somewhat pointedly ironic.

Left are the entries for Henry Debosnys under the column headings "Religious Instruction," the title of the commiting official, the official's name, and the status of the inmate's health upon in-take: respectively, "P" for Protestant, "Coroner," "Pease" and "Poor."

An attoney, Clark M. Pease served as Crown Point Justice of the Peace and as an Essex County coroner at various times during the 1880s and later moved to Troy, NY where he became commander of that city's Grand Army of the Republic Post.

In the column space for Debosnys under the heading "When Removed," someone appears to have written in pencil the word "Hung."

The "When Removed" column is the last column iin the ledger two-page spread for inmate information entries. It was normally used for entering the date of when a prisoner sentenced to prison or reformatory was actually "removed" from the jail and taken to that prison or reformatory. It was not meant when a prisoner was "removed" from this world to the next. However, the use of what appears to be pencil in writing the word "Hung" suggests that this note may have been added much later, perhaps even years later. Had the term been written at the time of the execution, the keeper of the ledger would have likely used pen as he had with all other entries on that page and as he had on the pages before and pages after it. Additionally he might well have used the term "executed," instead of the incorrect term "hung." If a variant of the latter word was required, the proper phrasing would have been "hanged."

|

The Elizabethtown Post's "Friday run" story remarked upon Debosnys' "poor" state of health at the time of his court appearances.

"At the time of his trial he was very feeble, apparently hardly able to walk alone, but very soon after sentence his appetite and strength returned to him, and he has slept and eaten soundly and heartily ever since."

Efforts to have the governor commute the sentence on grounds of insanity failed. The inmate exhibited behavior as a prisoner considered normal by medical examiners and jail staff. He spent his time writing, drawing, and conversing with occasional visitors, including the 1883 "Post" editor.

Among the things Debosnys wrote was a kind of grandiose autobiogaphy in two installments, the second of which ran next to the story of his execution. He dictated his so-called life history to the "Post" editor who printed it without comment as to how much credence it should be given.

The front page of the newspaper, that proclaimed A. C. H. Livingston as editor and proprietor, also proclaimed itself "Devoted to politics, science, agriculture and whole interests of the people." Evidently Livingston figured his readers savy enough to identify a spinner of tall tales when they encounter one.

The rather fanciful tale -- in which Debosnys claimed participation in a number of Artic expeditions, numerous wars on various continents, a few marriages, and sundry intrigues, one of which required his taking on the name of Henry Delectnack Debosnys -- began simply enough: with his birth May 16, 1836, at Belem, Portugal, on his uncle's "plantation."

Nothing in his dictated autobiography addressed how he became a house and barn painter and whitewasher in rural Essex County where he married a widow on June 8th, 1882, only about a mother after they first met and only a matter of weeks prior to her being killed.

Betsy, who had four daughters, was described as a "large middle age woman" who weighed as much as her husband who was described as "small, weak."

His main interest in her appeared to have been the small farm she had inherited from her first husband.

The prosecution developed, through the woman's 18 year-old daughter's trial testimony, the suggestion that Betesy had been resisting her new husband's demands she deed the farm over to him and that this figured into his killing her.

The court-appointed defense (which included A.K. Dudley, father of the future regional Commissioner of Immigration Fred W. Dudley who relates to the "Chinese Jail" page in this web presentation) readily acknowledged Henry killed Betsey.

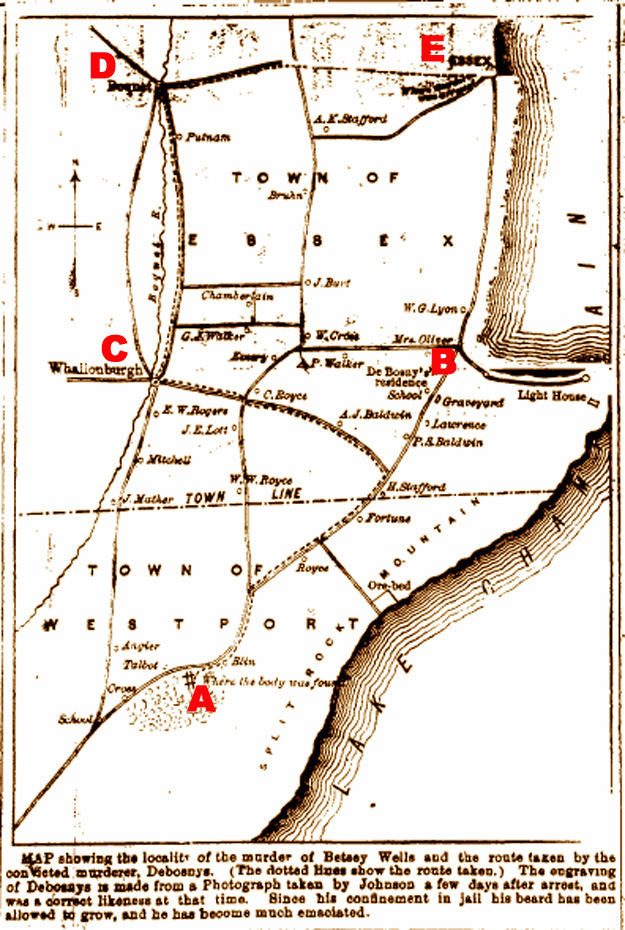

Above: Image of map accompanying The Elizabethtown Post March 15, 1883 story of Henry Debosnys trial. The webmaster has inserted red letters into the image to called attention to where the body was found ("A"), to where the Debosnys home was situated ("B"), and to the round-about way Debosnys drove (through localities "C" and "D") to get to Essex village ("E") where he was spotted and arrested, whereas the direct route from where the body was found would have taken him right past his own house. |

But his lawyers argued the violence was done in a drunken rage without prior planning and therefore it constituted murder second degree having prison as the penalty, not first degree having death as the penalty.

The trial lasted less than two full court days and the jury took only eight minutes in reaching its verdict convicting him of first degree murder. After his sentencing in early March, Debosnys had sold his body to Dr. W. E. Pattison of Westport for $15 and spent the money for candy, peanots and other "nick-nacks."

On gallows constructed by August F. Woodruff of Elizabethtown, the execution took place April 27, 1883, at 11:52 a.m. when Sheriff Rollin N. Jenkins pressed his foot upon the spring releasing the trap door under Debosnys, sending him to his death as a large assemblage watched. It is belived he died instantly of a broken beck.His body showed no movement suggestive of death throws and struggling for breathe. Nevertheless, an interval of several minutes -- 12 by one report, 16 by another -- was taken before officially declaring him dead.

The Plattsburgh Sentinel of May 4, 1883, in reporting the execution, praised the way the sheriff had implemented the sentence and indicated the kind of gallows employed:

SUPERIOR ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE EXECUTION

Capt. R. L. Jenkins, Sheriff of Essex County, is entitled to much credit for the

admirable and perfect manner in which he

has performed his part. Attending the recent execution at Windsor, Vt.,

Above is an image of the Vermont Prison at Windsor where on March 30, 1883 Emeline Meaker became the first woman executed by hanging in that state. She had been convicted of the strychnine death of her husband's 10-year-old arphaned half sister Alice whom she had beaten, starved and otherwise abused about a year before killing her. Mrs. Meaker resented her husband's agreeing to take the girl into his home from the orphanage with a $400 stipend. Essex County Sheriff Rollin L. Jenkins attended the Emeline Meaker execution at Windsor to prepare himself for carrying out the Debosnys execution. |

he familiarized himself as much as possible with

the detail, and was so much pleased with

the gallows used there that he patterned after

it largely. The work was done by Mr.

A. F. Woodruff, of Elizabethtown, and

was a first-class job.

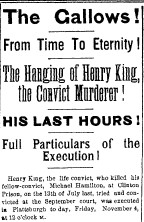

THE MODE OF EXECUTION

There are two methods of constructing a

gallows. One is by a weight attached to

the other end of the rope, which falling

suddenly jerks the body up from the

ground. This style was used at the execution of King, at Plattsburgh.

The other is by a drop in the platform on which the

prisoner stands, and which when a spring

is touched. let the prisoner through

the platform his entire length before the

slack rope is used up and his motion is

suddenly arrested.

Above is an image of the multi-deck headline and opening paragraph of The Plattsbourgh Sentinel Nov. 4, 1881, story on the rope execution of a "lifer" at Dannemora, Henry King, convicted of killing a fellow inmate Michael Hamilton in the Clinton Prison July 13 that same year.The kind of gallows used at the King exection in the Clinton County Jail yard was cited in the newspaper's May 4, 1883 story on the Debosnys execution, excerpts of which appear on this web page. |

The latter was used at

Elizabethtown with excellent success. It

is very simple in its operation, and of

necessity very effective.

EXAMINING THE SCAFFOLD.

On the morning of his execution, at

about nine o’clock he was permitted to examine

the scaffold on which he was to be

hung. A few reporters and officers were

allowed in the yard.

Washed, shaved,

and with new clean clothes and in white

shirt sleeves, and smoking a cigar, he

made his appearance in a very business-like

way, ran hastily up the steps, and took in

the situation at a glance. He tried the

knot and requested that it be soaped more:

that it might slip more easily; he cautioned

the Sheriff to have plenty of slack to the

rope and inspected carefully the trap on.

which he was to stand.

In his conversation

he laughed quite hearti1y, and

in returning to the cell bowed to the bystanders,

and was permitted to shake

hands with one or two whom he recognized.

HIS RELIGIOUS BELIEF.

Above is an image of the headline and illustration accompanying The Plattsbourgh Sentinel May 4, 1883 story of the Debosnys execution, excerpts of which are presented on this web page. |

In conversation with his principal spiritual

adviser, Father Redington, of

Elizabethtown, we referred to the opinion that

DeBosnys was an infidel in his ideas of religion,

which the Reverend gentlemen very

warmly repudiated.

DeBosnys had made

a general confession (not however of this

particular crime, of which he protested his

innocence) and had that morning partaken

of the communion at the mass, himself

serving the priests.

At their last religious

rites, there were present also Father Joseph

Butler, of Ticonderoga, Father John J.

Devlin, of Keeseville, and Father R. J.

McKeown, of Springfield, Mass. They

quoted him as saying, “The judgment I

am to meet today fades away in the light

of the judgment I am to meet tomorrow.”

The priests, like all spirituaL advisers,

were naturally hopeful for his soul. In

speaking of DeBosny's educational attainments,

they assure us that from personal

knowledge of the languages he could speak

good Italian, Spanish, French and Portuguese.

HANGMAN'S DAY.

Above: A key paragraph of The Plattsbourgh Sentinel May 4, 1883, story of the Debosnys execution, excerpts of which are presented on this web page. |

Friday last, April 27, the day of the execution, was a cold, dreary day, but it did

not prevent a large attendance from a

majority of the towns in the county, most of

them driving in that morning, and at noon

probably two thousand people were

standing on the common outside the jail yard,

where they could see the head and should-

ers of the prisoner before the drop fell.

Among the visitors present from abroad

were Truman N. Thomas, Sheriff of

Warren county, Dr. G. B. Streeter, of

Glens Falls, and Dr. Sawyer, of Ausable

Forks. Among the representatives of the

press were B. S. Brennan, Troy "Telegram,"

Thomas. A. Keith, Troy "Press," E. R. Mann,

Albany "Argue," Hurstell Colvin, Glens Falls

"Times," and W. H. Tibbetts, "Ticonderogian."

"The Plattsbnrgh Telegrarn" was represented

by its local reporter, Mr. Davis, and the

Troy "Times" by their local reporter, Mr.

W. S. Brown, of Elizabethtown. "The

Elizabethtown Post" was represented by its

editor, and the "Essex County Republican"

by one of its publishers, who also reported

the trial.

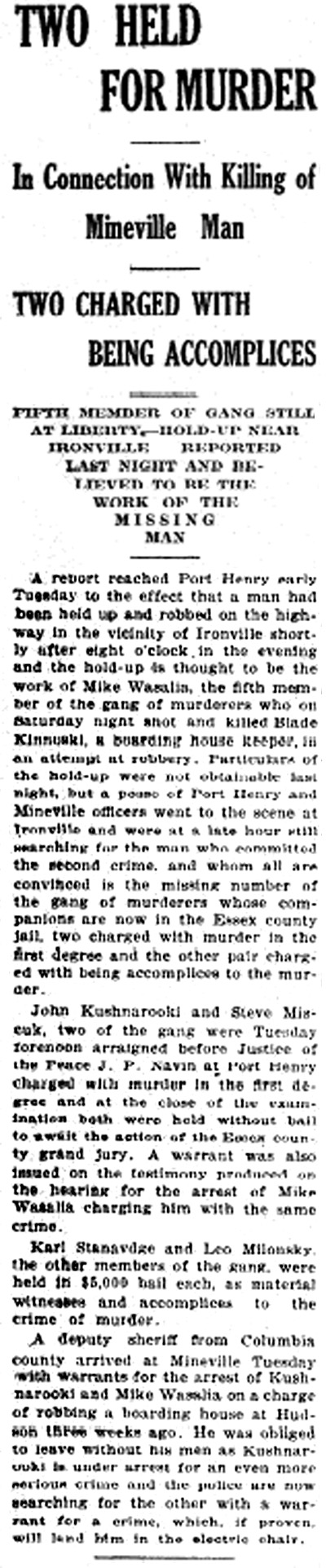

3RD & 4TH OF FOUR EXECUTED: JOHN KUSHNIERUK & STEPHEN LISCHUK

As noted near the top of this page, 35 years separated Essex County's second rope execution (Henry D. Debosnys, 1883) and the third and fourth executions resulting from an Essex County capital murder case (John Kushnieruk and Stephen Lischuk, 1918, in Sing Sing's electric chair).

No. 3 and 4 also had entries in that same ledger but they had company -- three others whose names also appear as entries in connection with the case, one as co-defendant and two as material witnesses.

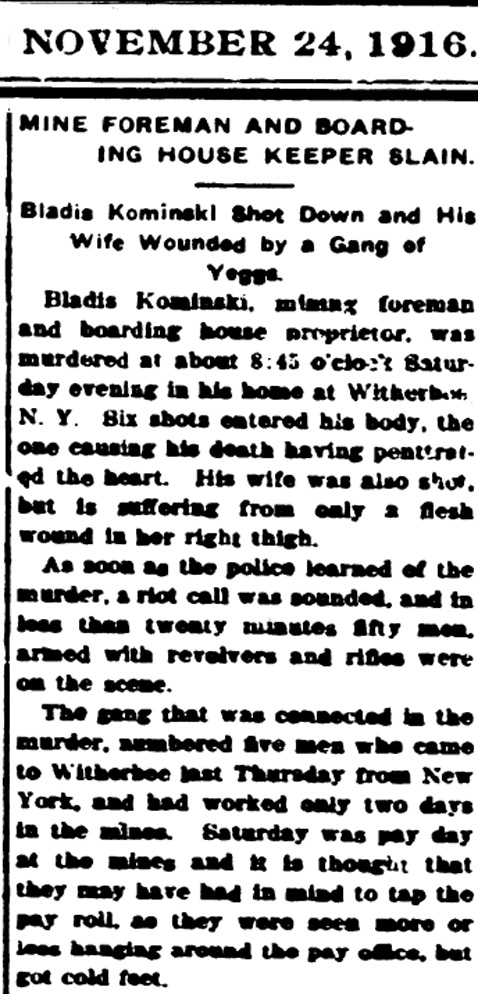

Though still difficult to read, above is a somewhat enhanced version of the archived image of The Elizabethtown Post Nov. 23, 1916 story of Mineville murder-attempted robbery, from the Northern New York Historical Newspapers web site provided by the Northern New York Library Network.

|

One of the first local newspaper stories on the case appeared in The Elizabethtown Post on the Thursday (Nov. 23, 1916) following the murder-attempted robbery. [Though still difficult to read, on the right side of the screen is a somewhat enhanced version of the archived image of 11/23/16 story that quite possibly was written by editor George L. Brown himself.] The opening sentence's reference to the suspects as "four foreigners, Russians and Poles" may reveal as much about the early 20th Century rural Northern New York mindset as it reveals about the suspects' national backgrounds.

The Post didn't quibble about such niceties as "alleged," "police said," and "according to authorities." In keeping with the prevailing newspaper style of the day, the story, published well in advance of trial, flatly convicted them of the shoooting and killing of Bladius Commiskey, mine blaster, as he lay in bed and wounding his wife beside him Saturday night. . . .

The foreigners were nerved up with liquor for the premeditated crime. Their motive was robbery . . . . Sheriff Pool and a number of armed men captured the murderers and brought them to the Essex County jail in this village to await for action of the grand jury.

The murders had sized up the situation, knowing Commiskey, who kept boarders and was a sort of depository for certain mine workers, had money in the house and they deliberately went after it. This is the worst yet and calls for drastic action.

The last sentence is a bit of open editorializing within the context of a straight new story. Today such blatant editorializing within supposedly straight news stories is frowned upon within journalistic circles, although much opinion does find expression in articles tagged "news anaysis" and even "straight" news stories can be "slanted" in the way the facts are reported.

Above is an image of Plattsburgh Sentinel Friday, Nov. 24, 1916, story. The archived issue can be found on-line at the Northern New York Historical Newspapers web site provided by the Northern New York Library Network.

|

The Elizabethtown Post story of Thursday, Nov. 23rd, 1916 did not include any names of the "foreigners" arrested, but the next day's issue of The Plattsburgh Sentinel [image left] did include names, including a few with spellings that would later change.

The Sentinel reported "John Kushnarooki" and "Steve Miscuk" had been arraigned on first degree murder charges, a warrant had been issued for the arrest of "Mike Wasalia" on the same charge as their accomplice and that two men, "Karl Stanavdge" and "Leo Milonsky," were held as material witnesses.

"Bladius Commiskey" in the Post had become "Blade Kinnoski" in the Sentinel.

The Sentinel report noted that a deputy sheriff from Columbia County showed up in Essex County with a warrant for the arrest of "John Kushnarooki" and "Mike Wasalia" in connection with an earlier boarding house robbery; that one in Hudson, N.Y.

The deputy had to leave without "John Kushnarooki" because of a more serious charge -- that of murder -- was holding him in the Elizabethtown jail. The had to leave without "Mike Wasalia" because,, as the newspaper noted,, local plice were still hunting him "with a warrant for a crime which, if prove, will land him in the electric chair." That flat statement turned out untrue. The fugative would later be caught, tried, convicted but not executed.

The Essex County Republican story [partial image, below right] on Nev. 24, 1916, published what perhaps was the most complete and detailed of the early reports on the crime. The murder victim "Bladius Commiskey" in the Post and "Blade Kinnoski" in the Sentinel became "Bladius Kominski" in the Republican.

That paper provided details on the order in which four of the males connected to the crime were taken into custody. The first was Leo Milonsky who said he was forced to be a member of the murder party. He was located in Witherbee by Constable Davis and placed in jail at Mineville, being held as a witness.

"Carl Stankavadge" [another spelling variation] 16 years old and the youngest of the men was arrested at about 9:30 o'clock Saturday at Moriah Center by Constable Hughes. . . . Arrested shortly after midnight in Port Henry by posse members Roy Henry and John G. McDonald was "Steve Lisczuk" [another spelling variation] who gave his age as twenty-eight years. He is the oldest of the four involved in the murder.

About 19-year-old "John Kushnarook" [another spelling variation], the Keeseville-based newspaper reported that he was captured after an all-night's chanse in a swamp near Crown Point Sunday and was identified by Mrs. Kominski as the one who killed her husband.

Above is part of the archived image of The Essex County Republican Nov. 24, 1916 story of Mineville murder-attempted robbery, from the Northern New York Historical Newspapers web site provided by the Northern New York Library Network.

|

. . . . During the chase, members of the posse fired shots at the fleeing murderers. . . . Little is known of the history of the four men. They are Russian Poles but have been in the United States two years or more. Stankavadge and Kushnarook speak good English and one of the other men can make himself understood by English speaking people.

The Republican also provided more details about the victim:

The autopsy . . . was conducted Sunday afternoon at Woodruff's undertaking rooms, Moriah Center, by Doctors Corning and Brown, with Justice of the peace Navin acting as Coroner. It was found that six shots had entered the body . . . The one causing death entered the back under the right shoulder blade penetrating the heart.

Kominski had been a resident of Witherbee for nine years and was a well respected citizen. He had married six years ago. Besides his wife, he is survived by three small children. The funeral was held Thursday from the Polish church and [was] largely attended. . . .

Stankavadge made a complete confession of the crime. He stated that Kushnarook and Wasalia were the ringleaders of the gang and that all they did was to go to threse different town, work a couple of days, and then rob some of the other boarders and then skip out.

Stankavadge claimed he wanted out of the gang and tried to quit but that they force him to continue. He said Kushnarook killed Kominski.

Milonsky, who had been a boarder at Kominski for some time well in advance of the others, said he not been involved with them previously but they forced him to take part or "suffer the consequence."

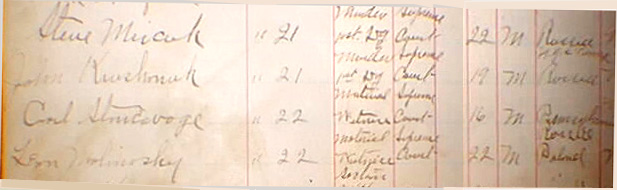

Above: Image of Elizabethtown jail ledger entries for the four men initially held in the 1916 Mineville murder case, the first two admitted Nov. 21 on Murder 1st Degree charges; the other two admitted Nov. 22 as material witnesses, the ages of the four ranging from 16 to 22 years, all with Russia or Poland listed as their country of origin.

|

The ledger left hand page of entries for the four [image right] show "Steve Miscuk" and "John Kuschnuk" - yet another spelling variation - jailed at the Elizabethtown facility Nov. 21st, 1916 on charges of "Muder 1st Dg." and show "Carl Stancavadge" and "Leo Milonosky" - still more spelling variations -- jailed there Nov. 22, each as a "Material Witness." Their counties of origin appear variously as "Russia" and "Poland." The in-take dates at the facility in Elizabethtown reflect that they had been held in various local lock-ups prior to being committed to the county jail. Note that, whereas the Republican story quoted "Steve Lisczuk" as giving his age as 28, thus making him the oldest of the four, the jail ledger -- referring to him as "Steve Miscuk" gives his age as 22, the same as that given for "Leo Milonosky."

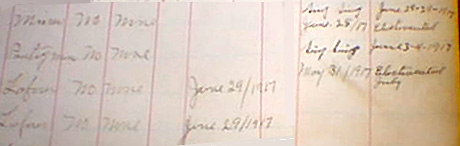

Above: Image of the right hand page entries in the Elizabethtown jail ledger for the four men initially held in the 1916 Mineville murder case. They show "Miner" (Steve Miscuk) and "Pantryman" (John Kuschnuk) recorded as sent to Sing Sing for electrocution and show "laborer" (Carl Stancavadge) and "laborer" (Leo Milonosky), the material witnesses, released "June 29, 1917."

|

The ledger right hand page of entries for the four [image right] show "Steve Miscuk" listed with "Miner' as his occupation, "John Kuschnuk" as "pantryman" and "Carl Stancavadge" and "Leo Milonosky" each listed as "Laborer." The latter pair, who had been held as material witnesses, were listed as both released "June 29, 1917." The "When Sentenced to State Prison" column for "Steve Miscuk" listed "June 28, 1917" and listed "May 31, 1917" for "John Kuschnuk."

The next column that also happens to be the last -- for "When Removed" entries; that is, when removed from the jail for transport to state prison -- lists "June 28-29, 1917" for "Miscuk" and "June 3 -4, 1917" for "Kuschnuk." It also correctly lists them as having been "electrocuted." But under "Kuschnuk" appears the word "July" which seems to have no relevance since his execution took place May 23, 1918 and the "Miscuk" execution took place about three weeks later -- on June 13, 1918. Perhaps the "July" reference applies to the original July 13, 1917 date set for his execution.

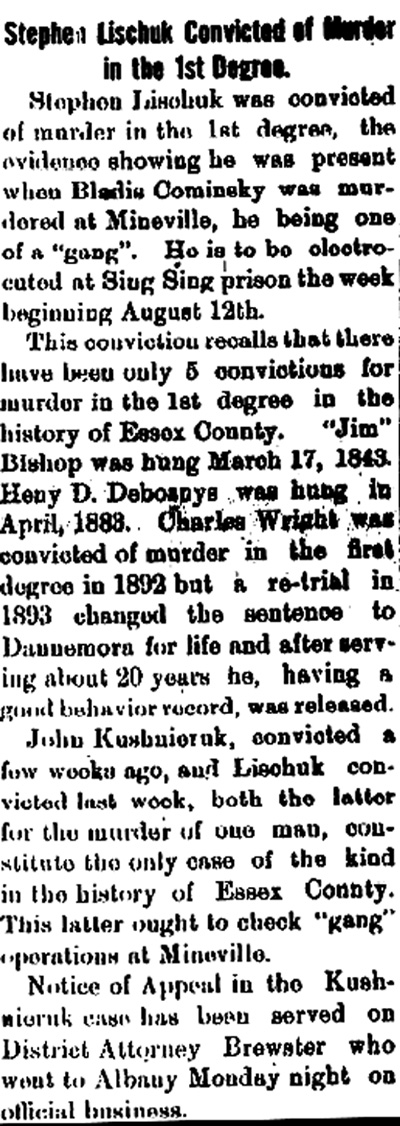

Above: Image of The Elizabethtown Post July 3, 1917 story reviewing prior first degree murder convictions in Essex County, NY.

|

The Elizabethtown Post of May 31, 1917, [image not shown here] reported the brief trial of "John Kushnieruk" -- yes, another variation --- with jury selection taking up Monday and Tuesday:

Wednesday morning the trial proper commenced, District Attorney Breweter and Harry E. Owen conducting the prosecution, Ex-District Attorney Patrick J. Finn and Patiick J. Tierney defending the accused.

20 witnesses were sworn for the prosecution, including the widow

of the murdered man and two others who swore they saw Kushnieruk

fire revolver shots at Comninsky. Late yesterday afternoon the prosecution rested.

Today has been occupied by the defenee, summing

up and charging the jury.

After deliberating 13 minutes jury brought in a veidict of guilty

of murder in the 1st degree, the first conviction of murder in the 1st degree in Essex County in 25 years.

Sentenced to be electrocuted the week beginning July 15th.

The Elizabethtown Post of July 3, 1917, in an article [image left] headlining the coviction of "Stephen Lischuk" -- yes, another spelling variation -- devoted most of the piece to reviewing Essex County first degree murder history. Almost certainly editor/history George L. Brown wrote it.

The fact, as reported in other local newspapers, that the jury took all of two hours to deliberate Lischuk's fate, may have been due to at least a bit of hesitancy to render a first degree verdict, for which execution was mandated.

After all the prosecution testimony was to the effect the accused had not actually been in the boarding house bedroom where and when the murder took place but had been on guard at the boarding house door, ready to prevent anyone entering or leaving.

Such participation constituted felony guilt in the murder, but the question of whether the culpability rose to the level of first degree guilt may have given a few of the jurors pause.

IRONY: REPUTED RINGLEADER WASILIA ESCAPES CHAIR, LATER ESCAPES PRISON

Above: Image of Sept. 10th. 1917 ("ditto 10") entry in the Elizabethtown jail ledger for "Michael Wasilia / John Smernoff / John Smith" on the charge of "Murder 1st Deg" to await action in "Supreme Court."

|

The irony is that fugative Michael Wasilia, whom Kushnieruk and Lischuk trial prosecution testimony placed in the boarding house, firing his weapon there and wounding the wife, would later be captured, tried but escape the electric chair as a result of being convicted of second degree, not first degree murder.

Wasilia entry listed age as "25' and place of origin as "NYC."

|

The fugative's capture was anticipated months before it happened. The Adirondack Record, published in Au Sable Forks, carried a story July 13, 1917 headlined "Man Who Shot Mineville Woman Seen in New York" that read:

Above is an image of the Sept. 11, 1917 Plattsburgh Sentinel story of Michael Wasalia's capture. Below is the Nov. 1st, 1917 Elizabethtwon Post story of his trial and conviction.

|

The Essex county authorities have

hopes of eventually capturing Mike

Wasalia, a member of the gang who

murdered Blatis Comminsky at Mineville last November and for which two

of them.

Kuschnicuk and Leschuk, are

to die in the Sing Sing electric chair,

the former during the week of July

15th and the latter during the week of

August 12th.

A New York employment agency man, who had sent the

murder gang to Mineville, and who

was a witness at the two trials, says

he saw Wasalia in New York twice last

winter.

This, however, was before he

knew that the man was wanted for

murder.

Wasalia, according to the evidence

brought out at the trials, was the man.

who shot and slightly wounded Mrs.

Comininsky at the time her husband

was killed.

He is regarded as the most

desperate member of the gang.

The

fact that he succeeded in eluding the

large body of men who were on his

trail after the murder is evidence that

he possesses considerable shrewdness.

His capture would mean that be would

follow his two confederates to the electric chair.

The prediction of that last sentence in the The Adirondack Record story would prove wrong, as illustrated by the image of Elizabethtwon Post Nov. 1st, 1917 story [below right] of his murder conviction, not for first degree carrying the death penalty but for second degree bringing a prison term.

One of more interesting stories concerning Wasalia was published in Ticonderoga Sentinel Sept. 20, 1917, after capture but before trial. Under the multi-deck headline "‘Wasalia Ignorant of

Companions’ Conviction, Did Not Know Lischuk and

Kushnieruk Were Sent to

Chair" it read, in part:

Captured in New York last week

Mike, Wasalia, wanted for the murder of Bladis Comminsky and shooting of Mrs. Comminsky at Witherbee

last November and turned over to

the Essex county authorities, said

that he was entirely ignorant at the

arrest, conviction and sentence to

death in the electric chair of his two

companions in the crime, Stephen

Lischuk and John Kushnieruk, the

execution of whose sentences have

been stayed by appeals taken by their

attorneys.

He told Officers William

Vogan and Lawrence Murray, who

brought him from New York, that he

did not know that Comminsky had

been killed. He had watched the papers, he said, and, seeing nothing of

the affair in print, had concluded

that Comminsky had escaped with

his life and he gave the matter no

great thought thereafter.

His story of his escape from the

officers at Crown Point the morning

after the murder is interesting.

Wasilia entry ends with his "Nov. 17" prison sentence of "20-to-life."

|

He

and Kushnleruk, in the black hours

of the morning, as they walked south

along the railroad track, saw officers

on thc track ahead and they immediately turned into the swamp north

of the Crown Point station and separated.

Kushnieruk, though Wasalia

did not know it, became lost in the

swamp and, after wandering around

aimlessly, laid down and finally gave

himself up.

Above is an image of The Adirondack Record July 26th, 1918, story about the Essex County Board of Supervisors committee set up to decide who was to receive the $500 reward for helping capture Michael Wasalia.

|

Wasalia. however, had

better luck. He circled southward

around the three officers, Vogan,

Murray and Carpenter watching the

railroad, then went around the Crown

Point station and struck the state

road. In the darkness he was not

seen by the officers. He continued

south unmolested and reached Fort

Ticonderoga just in time to board

the last car of the southbound train

as it was pulling out.

He paid his

fare an the train and went directly to

New York.There he had been ever

since the crime with tbe exception of

going for short intervals of time,

once to Massena, to other places

for employment.

When Wasalia and Kushnieruk

ran into the swamp at Crown Point,

they were fired at by both officers

Vogan and Murray. Their bullets,

Wasalia says, all came uncomfortably close and one struck the lobe of

one of his ears, causing it to bleed

more or less for three days and giving him great inconvenience.

Continually seeking employment

through employment agencies, he

dealt with one agency that sends

men to Witherbee, Sherman & Co. at

Mineville.

An official of this agency,

a witness in the trials of Lischuk and

Kushnieruk, learning that Wasalia

was also wanted for the same murder

kept watch for him and finally he located his man.

Wasalia was then

kept under surveillance, the employment agency man evidently looking

for a chance to capture his man alone

and thereby secure all of the five

hundred dollars reward ottered for

his capture.

The opportunity not

presenting itself, last week he sought

the services of an Italian detective

just after Wasalia had left the agency

office.

Above is an image of The Elizabethtown Post August 28th, 1919, story about the Essex County Board of Supervisors endorsing Sheriff Poole turning over to the court the $500 and accrued interest in the dispute among claimants to the $500 reward for helping capture Michael Wasalia.

|

The detective followed Wasalia into a saloon and the latter, becoming

suspicious, took to his heels.

The detective, aided by a policeman,

ran him down and he was held to

await the arrival of officers from

this county. Just how the five hundred dollars reward will he distributed is, therefore a problem for Sheriff Pool to solve.

That last sentence of The Ticonderoga Sentinel Sept. 20, 1917 story alludes "just how the five hundred dollars reward will he distributed" as a "problem for Sheriff Pool to solve." But as the image of The Adirondack Record July 26th, 1918, story above and the image of The Elizabethtown Post August 28th, 1919, story right show, Sheriff Pool first turned to the Essex County Board of Supervisors to resolve the question and later the claimants turned to the courts to decide the issue. Various research interrogatories submitted to the on-line archives of Northern New York newspapers have failed to find any report of a court decision or court-arranged settlement in the matter.

The 1919 reward dispute story was not the last time the Wasalia case produced headlines. The Plattsbourgh Sentinel on Page 4 of its July 25, 1924, carried a story about the his escape from Clinton Prison. The multi-deck headline read: "Smallest Inmate at Dannemora Flies: Wasilia, Mineville Murderer, Eployed in Prison Hospital, Walks Out"

Above is an image of the July 25, 1924 Plattsburgh Sentinel story of Michael Wasilia's escape from Dannemora.

|

Although the escape account said the murder for which Wasilia had been sentenced 20-to-life was "the result of drunken brawl in a saloon in Mineville," instead of describing it as a boardinghouse robbery attempt gone bad, there can be little doubt that report refers to one and same Michael Wasilia convicted in 1917 for the 1916 slaying of boardinghouse keeper Bladis Comminsky.The 1924 escape story notes that Wasilia, whose age at the time of his escape was given as 33, began his prison sentence Nov. 2, 1917.

Could there have been in 1924 another Clinton Prison inmate Michael Wasilia, in his mid-20s, who began a 20-to-life prison sentence in November, 1917 at Dannemora for a different Mineville murder? Not very likely.

Various research interrogatories submitted to the on-line archives of Northern New York newspapers have failed to find any report on exactly where and when Wasilia was recaptured. However, The Plattsbourgh Sentinel of April 10, 1925 included a very brief reference to him in reporting on a number of cases that District Attorney B. Loyal O'Connell had scheduled to present to a grand jury. Under a "Wednesday, April 15" heading, one item listed as scheduled for grand jury presentation that day read: "Michael Wasilia, charged with escape from prison."

On April 23rd, 1926, The Plattsbourgh Sentinel featured a front page story whose headline's top deck read: "Convicts Who Escaped Get Year Apiece."

The two-sentence single paragraph related to that part of the headline reads: Three Dannemora convicts, captured after escape, were each given an additional year to serve. They were Kenneth Newvine, Geo. Clark and Michael Wasilia.

George Clark and Kenneth Newvine, the other two recaptured escapees mentioned in the 1926 story had escaped in October 1925 and were at large only a matter of a few days before recapture, according to The Plattsbourgh Sentinel of Oct. 27, 1925.

INMATE IN-TAKE LEDGER USEFUL RESOURCE FOR HISTORICAL RESEARCH

From a historical research perspective, the ledger entries in the three Essex County first degree murder cases that ended in executions are useful in that they provide fixed points of reference in the midst of conflicting name spellings, dates and reported charges. Not that the ledger entries are necessarily more accurate than any of the name variations and background details published in the on-line archived local and regional papers. But at least the information entered in the book represents something "officially" recorded following direct contact with those charged.

Furthermore, the local weeklies and bi-weeklies of the period tended to be less concerned with framing their news in terms of exact dates or lacked the luxury of easily looking up the relevant past dates in a continuing story. The jail in-take and removal-to-prison dates in the entries proved helpful in tracking the murder cases through the on-line archives.

1ST WOMAN IN COUNTY HISTORY CONVICTED OF 1ST DEGREE MURDER

Above is an image of the headlines and opening paragraphs of the Nov. 28, 1935 Adirondack Record reprinting of the Albany Knickerbocker Press story about the two trials of Fannie Soper.

|

This web page on Essex County first degree murder cases resulting in executions would not be complete without at least passing mention of Mrs. Fannie Soper, 48, the first woman in the county's history to be convicted of first degree murder. She was found guilty of fatally shooting her husband, veteran Deputy Sheriff William Henry Soper, 65, about noontime May 28, 1925, as he napped on a kitchen couch in their Boquet home.

Sentenced to die in the Sing Sing electric chair Jan. 3rd, 1926, Fannie Soper -- her full name was Hapillina Denton Cutting Sykes Soper (she had been married twice before and married Soper only about two years prior to his death) -- won a new trial when in July 1926 the state's highest court overturned the conviction.

On Nov. 20, 1926, a year and day after her first

conviction, Mrs. Soper again was convicted of murder but this time for second degree. Fannie Soper was sentenced

20 years to

life in Auburn Prison. Essex County Sheriff and Mrs. Charles Orr accompanied her both on her trip to Sing Sing and on her trip to Auburn.

Mrs. Soper was among a group of women prisoners from Auburn who became the first inmates at Westfield prison farm in New Bedford in the summer of 1933.

She died June 28, 1945, in Champlain Valley Hospital after a three-week illness. About a year before her death, Mrs. Soper had moved to Keesville to be with her married daughter.

-- NYCHS webmaster

List of Links to Other Pages in New York Correction History Society's

Essex County Jail History Web Presentation

| |

| |

|