|

In connection with the anticipated opening of a new Essex County Jail in Lewis, N. Y., during the summer of 2007, the New York Correction History Society (NYCHS) created this "virtual tour" of pre-computer record keeping at the county's old jail in Elizabethtown. This part of the tour examines the ledger (left) entitled Record of Commitments to Essex County Jail.

If (as various other sources indicate) the jail dates from 1868, this ledger would not have been the first one used for its inmate in-take entries. The first entry was for one Frank Fanning who was jailed June 26, 1879 on a Burglary charge and sentenced to serve "1 year."

Even though inmate Fanning's entry is the first in the ledger, that does not mean inmates who were committed to the jail during 1879 after June 26 were all entered on the page. In fact, his is the only specific 1879 in-take date entered in the book that really should be viewed as basically beginning in 1880. This working premise is reinforced by notations immediately above and below the Fanning entry.

The notation above the Fanning entry -- and above the column headings -- was written in what appears light ink or pencil: E. H. Talbot, Sheriff, Jany 1st, 1880. The notation written below the Fanning entry appears in the column entitled "When Committed" and reads: found in jail when took office. 1880. Fanning was released June 26, 1880 after having served his sentence.

Besides Fanning, Sheriff Talbot's notation about inmates found in jail when he took office as sheriff apparently applied as well to three other inmates being housed in the jail as of Jan. 1st, 1880: two men (Flemming and Hathaway) held as vagrants and one Daniel Roonan who was awaiting trial on a Larceny charge involving a $40 item and who was subsequently was removed to state prison Jan. 8, 1880 to serve a "prison 3-yrs" sentence (at presumably Clinton aka Dannemora).

The ledger's entries -- that end June 28, 1924 -- span 45 years, from the late 19th Century into the early 20th Century. They begin on numbered Page 2 and end on numbered Page 268. Because the entries for an inmate were spread over two facing pages, beginning with the name entered on the even numbered page and ending on the odd numbered page with the date of the inmate's removal to prison or wherever, only the even numbered page numbers are listed in this web page presentation to identify the entry information. Each page had 27 lines for information to be entered.

Unlike the other two ledgers in this presentation, the inmate commitment record book entry lines extend across two facing pages in a manner akin to our computer era spread sheets.

Rather than being a generic record book purchased off a shelf or from a mail order warehouse, the ledger obviously was printed especially for Essex County Jail.

While each even numbered (left hand) page features at its top the words "Record of Commitments" in large lettering, each facing odd numbered (right hand) page features at its top in the same lettering the phrase-completing words "To Essex County Jail." The other two ledgers in this presentation show no evidence of having been custom printed for the county jail. Indeed, the operating expenses audit ledger has near the front a group of tabbed pages meant to serve as an alphabetic index. But that feature went unused because it was completely irrelevant to the purposes for which the book was in fact used.

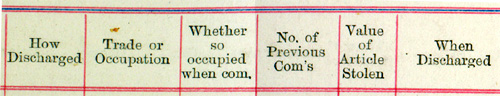

Whether the column headings on the inmate commitment record book pages were custom printed for Essex County Jail is different question. They could have been standard for such inmate record books, with only the jail's name at top changing. But even if they were printed in accord with Essex County Jail's custom order, the headings were most likely in keeping with the practices followed in jails around the rest of the state and country.

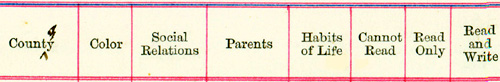

Some column headings were what one would expect, such as "Name of Prisoner," "When Committed" (to jail), the "Offense," the "Term of Sentence," any "Fine" imposed, as well as the "Age" and "Sex" of the inmate. But others are a bit more unusual by today's standards or at least the terminology that was employed is. Examples: "Color" instead of race, "Religious Instruction" instead of religious affiliation, "Social Relations" instead of marital status.

Next to the "Social Relations" column (where the entries were almost invariably either "single" or "married") appeared a column entitled "Parents." Its entries were "both," "living," "none," "mother" or "father."

Since the ledger did not provide within its pages for such family contact information as the addresses and names of parents and/or spouse, presumably another ledger or different record material, such as index cards, contained that data as well the inmate's date of birth, address, and description, etc. The sheriff's office would have been the arresting agency in most cases. So presumably any identification details gathered in connection with the arrest would have been recorded within the same department and remained accessible if and when needed. Given that the jail's capacity was only a few dozen at most, keeping track of who was who among the inmates was far less of a problem than in big cities where jail inmate populations ran into the hundreds, if not thousands.

On even numbered pages the heading of one column was printed as "County." But that was corrected with a penned "r" to "Country" through 1883. Thereafter it continued to be understood as "Country" even without the penned "r." Entries were mostly "U.S." But by March of 1895 (Page 58), the column heading came to be understood as printed -- County -- with "Essex" entries dominating.

One column was provided for "Habits of Life" that evidentially addressed destructive life style issues such as alcoholism. Presumably the inmates themselves supplied the kind of personal information that the record keepers needed to decide whether to write "good" or "bad" in that column. Occasionally they wrote "intemperate." Even more rarely the term "fair" was entered, a surprising pattern. That those inmates with "bad" life habits would outnumber those with "good" habits was to be expected, but one would not have imagined the latter outnumbering those whose habits were only "fair." Perhaps more listed as "good" and more listed as "bad' deserved being listed as "fair." The record keepers may have tended not to see inmates' life styles as a mix of good and bad, but only in terms of either/or.

Instead of entering the inmate's educational level by grade level, columns labeled "Cannot Read," "Read Only," "Read and Write," "Well Educated," "Classically Educated" provided space for entering the appropriate information. Presumably, "Classically Educated" in 1879 meant a college graduate.

In 1879, why would a jail administration want to know about the inmate's education level beyond establishing the basic ability, or lack thereof, to read the institution's rules and to sign his name on its forms? An answer to that question can not be derived from the ledger itself. But the jail ledger's evident interest in knowing the educational level of its inmates reflects trends in the penal profession at the time when the book's column headings were printed and when the first entries were being penned in those columns.

This was the period marked by emergence of the reformatory movement with its emphasis on education tailored to the individual inmate's abilities and needs. To some extent, reformatories' instruction of inmates in secular subjects grew out of the efforts by pre-reformatory-era chaplains and spiritually motivated reformers to provide religious instruction to prison and jail inmates. The Prison Sabbath School movement involved clergy and volunteer lay people providing not only lessons from the Bible but also reading skills so the inmates could scan the Scriptures on their own.

Unless illiterate prisoners could be taught to read, giving them bibles and religious tracts made little sense. Generally, chaplains were the leading advocates and pioneers of schools and libraries in jails and prisons, with books and lessons both religious and secular. That may be a clue to why the column heading was "Religious Instruction" instead of religious affiliation and why that column came immediately after those about reading, writing and level of education.

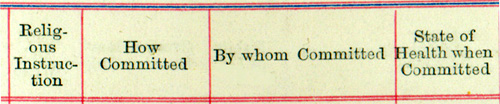

The fact that "Religious" was misspelled (the second "i" is missing) in the printed column heading reflects back on the ledger printer, not on the jail administration.

In a report -- excerpted elsewhere on this website in a presentation entitled 1869 NY

State

Prison

Chaplain

Reports -- the chaplain at the state prison in Essex's neighboring county, Clinton, complained about the lack of sufficient funding by the State Legislature to the prison library he oversaw. Chaplain J. A. Canfald wrote:

Pursuant with the statute to that effect, the Agent and Warden has freely supplied Bibles, school books and slates for the use of prisoners. Each man that can read has a Bible placed in his cell, and many not only read but study it with interest and profit.

Something over a year since Mrs. Elizabeth Comstock, of the Society of Friends, spent a Sabbath with us, and through her means we have since received of Robert Lindley Murray forty-five volumes of very valuable books for our library.

This is the only donation of books to our library since it has been under my charge, except a few Congressional documents.

The ledger’s first facing pages with entries (numbered Pages 2 and 3) begin with a few 1879 entries but the rest relate to inmates “committed” to the jail in early 1880, including one 13-year-old sentenced for petit larceny. His entries constitutes the 10th row on the facing pages. The ditto under “When Committed” refers back to January, making the date of admission Jan. 30, 1880. The “Term of Sentence” seems to be “30;” that is, 30 days. The keeper making the entry had a tendency to give his letter “o” a little curlicue.

Boardman’s “Country” of origin is listed as "U.S." The ditto under “Color” refers back to “White,” as do all the entries in this column on this ledger page. Unsurprisingly, his "Social Relations" entry is "Single." He is down as having "both" parents and being able to both read and write. Despite his life as then numbering only 13 years, his "Habits of Life" were recorded as "bad."

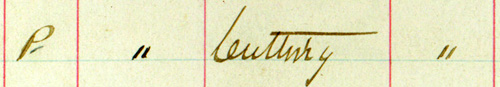

Boardman's "Religious Instruction" drew a "P" entry for Protestant. The ditto in "How Committed" (to jail) refers back to the office of county "Justice" and "By Whom Committed" gives that name as "Cutting." The boy's "State of Health When Committed" (to jail) ditto refers back to "good."

Boardman's "Trade or Occupation" is listed as "Farmer" and the ditto in the next column affirms he was "So Occupied When Committed" (to jail). The "Value of the Article Stolen" is recorded as $1.The "April 15/80" entry under "When Discharged" appears in conflict with entry "Order of Court" under "How Discharged" heading. Justice Cutting on Jan. 30th had sentenced him to 30 days for stealing something valued $1.

But the April 15th release date would seem to indicate the boy served way more than twice that amount of time. Could his "bad" Habits of Life led to his violating jail rules, resulting in the extra 45 days being added to the sentence?

Or was the $1 larceny conviction a legal device for placing the boy, under the supervision of the court? Perhaps his unruly ways had gotten beyond his farming parents' ability to control, Even though the law since 1865 had provided a mechanism for having a youth declared "disorderly" and placed under the court control, perhaps that process was too lengthy and uncertain for a farm family needing the boy back at work the fields come the spring.

Anyone with a better theory to explain how a 30-day sentence imposed in January 1880 on 13-year-old boy for a $1 larceny became a 75-day stay behind jail bars, please let us know and we'll post it here.

|

We shall soon be obliged to appeal to the benevolent for books, or do without them, unless our Legis- lature is more mindful of our wants than it was last winter. The $250 appro- priated one year ago last winter has been carefully expended, adding to our list 244 volumes, which, with the donation of Mr. Murray, made a handsome addition to our scanty library.

Our evening schools have been as successful as could be expected under our present system. My sincere thanks are due to those who have so faithfully taught in our Sabbath schools . . .

The images and captions above right display and discuss the information entered in the ledger for 13-year-old Frank Boardman who apparently served 75 days in Essex County Jail on a 30-day sentence in 1880 for a $1 larceny.

Boardman's is the 10th name on the first page of inmate names in the Essex County Jail ledger and the first name of an inmate under the age of 16. There were dozens of other juveniles -- even a few as young as 10 years old -- whose names are entered as inmates of the Elizabethtown jail during the decades covered by the ledger.

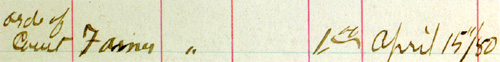

Above: Image of entry for "Harriet Stone" on June 23. 1880, charged with "Murder." age "13," gender "F."

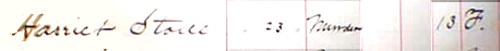

Below: Image of continued entry for her, noting her "Religious Instruction" as "P" for Protestant, that she was jailed on order of "Coroner Pease," that her health on in-take was "good" (ditto). and her occupation "servant."

.

|

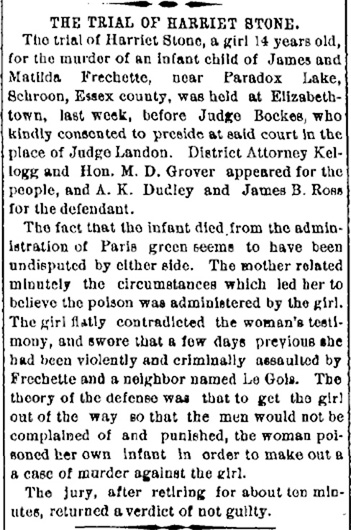

On the next page of inmate names, numbered Page 4, the second juvenile's name entered in the ledger appears -- that of Harriet Stone, 13, (see above images) whose occupation was listed as "servant." The charge: "Murder." The entry gives no details of the case other than that she was jailed June 23, 1880, on order of the "Coroner Pease." No disposition is entered. However, the Plattsburgh Sentinel, circa July 1, 1881, tells the extraordinary story of her acquittal by a jury after 10 minutes of deliberation. The report gives her age at the time of the trial as 14.

Above is from The Plattsburgh Sentinel circa July 1, 1881. The account was found using the Northern New York Historical Newspapers web site provided by the Northern New York Library Network. Click the image to access that site. Above is from The Plattsburgh Sentinel circa July 1, 1881. The account was found using the Northern New York Historical Newspapers web site provided by the Northern New York Library Network. Click the image to access that site. |

She had been accused of administering to the infant child of James and Matilda Frechette, a pesticide -- called Paris Green -- used on farms to kill potato bugs and other insects.

At trial, the teenager contradicted the mother's claims and countercharged that Frechette and a neighbor LeGola had "violently and criminally assaulted" her a few days prior to the baby's death. The phrase "criminal assault" was a euphemism that newspapers of that era (and well into the second half of the 20th Century) employed in cases of rape or other sex-related offenses.

The defense theory presented by her attorneys A. K. Dudley and James Ross portrayed the infant's death as perpetrated to frame Harriet so as to discredit her and to have her imprisoned, thus covering up the claimed attack on her by the two men.

Photos -- above of a Tenn. textile factory worker, 8, in 1910 and below of Pa. mine crew boys circa 1911 -- were taken by National Child Labor Committee photographer Lewis Hine. The NCLC evolved in 1904 from a Child Labor Committee founded in 1902 by the Association of Neighborhood Workers, an organization of settlement workers in New York.

|

For the 1881 jurors to have so immediately agreed they had reasonable doubts -- after having heard the two conflicting versions of the infanticide -- would seem to suggest they had, at the very least, serious reservations about the Frechettes' account.It also may be worth noting that the case did not come to trial for more than a year after the death whereas in that era the interval between arrest and trial usually was a matter of only months.

- William Roonan Jr., 13, a "laborer" from Ireland and whose education was listed as "poor," June 25, 1880. Served 15 days for assault. Page 6,

- Edward McKane, 13, a "laborer" who could read but not write, April 26, 1884. Served 15 days for larceny. Page 16.

- John Dwyer, 13, a "laborer" who could "read and write," April 30, 1884. Served 45 days for larceny. Page 16.

- Ellsmith Hammer, 14, and Allie Bryant, 13, "laborers," both committed to Essex County Jail March 23, 1887, for burglary and larceny, held for Grand Jury, sentenced to state prison June 10 and removed to it (unnamed; Dannemora?) June 11, 1887. Hammer could read and write; Bryant, "read only." Page 24.

-

Fred Stone, 14, from Canada, occupation "miner" (not minor) who could read and write, Feb. 16, 1888. Served 10 days for larceny. Page 26.

- A 14-year-old "farmer" named "Dan'l" who could not read, was committed to jail Nov. 16, 1888, on a "rape" charge and held for the Grand Jury. However, he was released April 17, 1889, having been behind bars about five months, apparently having served time for what must have been some considerably lesser charge than the ordinal felony. Page 28.

- Willie Croak, 13, a "laborer" who could "read only," April 9, 1889. Served 30 days for petit larceny. Page 30.

Images above and below are from a Lewis Hine photo of child garment workers sewing pieces together in their cramped NY tenement room Jan. 25, 1908.

|

Daniel McCabe, 13, a "laborer" who could "read and write," committed to jail June 9, 1889, on a larceny and burglary 3rd degree charge, held for Grand Jury, and discharged Dec. 17. The note on manner of discharge appears to be "sent. com." which could mean "sentence commuted." That would fit with the date so close to Christmas, traditionally a time for sentence commutations. Page 30.

- Fred LaGenette, 13, an 'laborer" who could not read, Sept. 24, 1889. Served 15 days for "b. of peace." Page 32.

- Fred Martin, 15, a "laborer" who could neither read nor write, Sept. 25, 1889. Served 30 days for "b. of peace." Page 32.

- Fred Smith, 15, and Freely Smith, 12, (brothers?) both "laborers" who could neither read nor write, Oct. 24, 1889. Both served 5 days for a petit larceny. The "5" was entered in the "Fine" column but the discharge date of Oct. 29th makes clear the "5" refers to days.

- A 15 year-old "laborer" who could "read and write," was held in jail May 31, 1890, for the Grand Jury on a burglary and larceny charge. He was "bailed" on an unknown date. No other data regarding disposition of the case was entered. Page 32.

- Carrie Darling, 13, from Nova Scotia, was held in jail on a "vagrancy" charge from, Oct. 2 to Oct. 21, 1891. She could "read and write" and is listed as having a mother living at the time. Whether the girl was a runaway is unclear as is how she came to be discharged. Page 38.

- Two Franklin County boys, 15 and 14, were held in jail Dec. 2, 1891, for Grand Jury action on burglary and larceny charges but the outcome of that is not shown. Page 40.

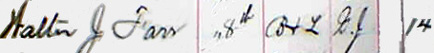

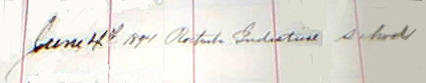

Above: Image of entry for "Walter" on Sept. 8, 1893, charged with "B & L." held for "G.J." (grand jury), age "14." Below: Image of entry for his being ordered to the Rochester Industrial School June 4, 1894.

|

Walter J. Farr, 14, a "laborer" who could not read or write, was jailed Sept. 8, 1893, on a burglary & larceny charge and held for Grand Jury action. He was sent June 4, 1894, to the Rochester Industrial School. Page 48. Elsewhere on this web site is a multi-page and multi-image presentation of A History of Penal and Correctional Institutions in the Rochester Area

by

Blake

F.

McKelvey, including the State Industrial School

- Also on Page 48, David Davis, 13, was sentenced Oct. 23, 1893, to 8 days for "Intoxication." (See image above.)

- Alfred LaCross, 15, a "laborer" who could "read and write," Nov. 24, 1893. Served 10 days for petit larceny. Page 48.

- On Page 52, the name of Ernest Stanton, 10, who could "read and write," appears as held in jail Sept. 8, 1894, for Grand Jury action on a burglary charge. The outcome is not noted in the 1894 entry. But his name appears again in the ledger -- three years later.

- Frank Flemming, 15, with "no trade" but who can "read and write," Jan. 11, 1895. Served 30 days on the charge of "M.M." (Malicious Mayhem?) Page 56.

- Melville James, 14, a "laborer" who can "read and write," Dec. 14, 1895. Although nothing is entered in the "Term of Sentence" column and "40" is entered in the "Fine" column, he is not discharged until Jan. 22, 1986 -- almost 40 days later. So the sentence was likely "$40 or 40 days." Instead "U.S." in a column corrected to read "Country," the heading was left as "County" and the entry was "Essex."

- Ernest Stanton's name appears again in the ledger. Page 66. This time he is 13 but again charged with a larceny. Under occupation, "school" is listed, the first such listing for an under-16 inmate. He is held for action of the "Supreme Court" on Dec. 1, 1896, and not discharged until April 27, 1897. The value of the article stolen is put at $5.50.

Whether this was a new larceny or a return to the previous larceny when he was 10 is not clear. Could he have received some kind of probation in 1894 because of his age then, but perhaps subsequently failed to live up to the terms of his conditional release? Under "Habits of Life," the entry for him is "bad." His entry in the column labeled "County" is a ditto referring back to "Essex," whereas his entry in 1894 reads "U.S."

- Clifford Jinks, 14, of Essex, a "laborer" who could neither read nor write, Sept. 23, 1898. Served 4 months for petit larceny. Page 78.

- Julia Canfield, 15, of Essex, jailed Jan. 24, 1901, on the charge of "vagrancy." Given that her entry under "Parents" reads "Yes" (understood as both living), the charge seems to have been used as a then legal device for making her subject to court supervision.

For the teenage daughter of parents living in Essex to be considered a vagrant raises questions. Vagrancy charges in that era, when brought against minors, often really involved allegations of waywardness. Was she a runaway? Was she really living on the streets? Or was she still at home but evidencing disapproved behavior beyond her parents' control? The word "bad" appears in both the "Habits of Life" and the "State of Health" entries for her.

Interestingly, on the face of the record as written, the court on Jan. 23 ordered her committed to the House of Refuge, the order resulting in her being jailed the next day Jan. 24. Did the parents first go to court about her, and then, having obtained the court order, surrendered her the next day to the jail pursuant to the order? The actual transport of her from jail to the House of Refuge is dated Jan. 29. Which House of Refuge is not specified. Page 92.

- Carl Hall, 14, of Essex, classified a "common laborer," who could "read and write," was jailed on a charge of "rape," June 6, 1902, and held for the Grand Jury. By court order he was sent "to Rochester" (Industrial School?) July 7. Page 100.

Above is a graphic pen sketch of social reformer Florence Kelley (1859-1932) whose National Consumers League, based in NYC, promoted boycotting goods lacking the NCL white label (below) signifying they were made in compliance with NCL standards regarding women and child labor.

|

James Jaquish, 15, of Essex, a "laborer" who could only read but not write, jailed June 20, 1905. Served 30 days for petit larceny. Page 116.

- A 10-year-old of Essex, whose first name was James and whose occupation was listed as "school boy," was jailed June 12, 1906, on a charge of petit larceny but ordered released the next day by the court. No disposition of the charge is shown. Page 120.

- Emma Farr (or Fan?), 15, and Addie Williams, 20, were both jailed on Dec. 10, 1906, on "disorderly person" charges, serving six month each and being released June 10. Emma's entries appear on the next line below those of Addie, so they were likely arrested together. Page 126.

- A 14-year-old "hotel clerk" of Essex was jailed Sept. 3, 1907, on a Grand Larceny charge but bailed out Sept. 25. The outcome is unclear but the date listed for his discharge in the matter was given as Nov. 16. Page 130.

- John Colburn and Frank Gre, both of Essex, laborers, and 14, were jailed Jan. 13, 1909 on a Burglary 3rd degree charge and held for the Grand Jury. They were discharged 6 months later -- June 17, 1809..Page 140

- Jacof Ruso, 15, of Essex, who could neither read nor write and had no trade or occupation, jailed for petit larceny July 20, 1910. Served 100 days. Page 148.

- A 15-year boy, who had both parents and could "read and write, was jailed May 7, 1912, on a forgery charge and held for Grand Jury action. The disposition is unclear. He was discharged June 19, 1912. Page 156.

- John Hanson, 15, was jailed July 12, 1913, on a Murder 1st degree charge. The entry on Page 170 gives no details about the case disposition other than the discharge date of Nov. 3.

However, the Plattsburgh Sentinel of Nov. 11 under the headline (image right) "Boy Murderer" provides details, including his appearing "last week" before Judge Pyrke who ordered him returned to the custody to the New York Catholic Protectory. The sentence was imposed after Essex County District Attorney Fred M. LaDuke accepted a Murder 2nd degree guilty plea by the defendant "in view of his extreme youth."

Hanson had been brought from the Protectory to the Patrick Cushing farm in Essex a few years earlier to attend the old man "in his dotage." The youth reportedly confessed to poisoning him with Paris Green, a potato bug killer, the same pesticide that also figured in the trial of Harriet Stone, 14, in 1881.

The confession attributed to Hanson was the effect that he thought getting rid of Cushing was a good idea since the man was "old and feeble."

The sentence by Judge Pyrke (former landlord of Essex County's "Chinese jail") directed that Hanson be confined to the Protectory until the youth turned 21. The institution, founded in the 1860s, provided custody, care, and vocational training to children -- orphaned. abandoned, or sent to it by courts or by the New York City Department of Public Charities and Correction. The boys division was run by the Brothers of the Christian Schools.

The Protectory's huge grounds -- 129 acres in what was Westchester and later the Bronx -- were sold for $4 million and became Parkchester, the 171-building complex erected by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company at the end of the Depression.

A number of the progressive reforms in "modern penology" can be traced back to the first protectory for youth, San Michele, founded at Rome in 1704 by Pope Clement XI, The 18th Century English prison reformer John Howard, during a visit there, noted a motto in marble on a wall that read:It is of little use to restrain criminals by punishment, unless you reform them by education.

Long before emergence of America's Auburn-type prison system, San Michele inmates worked together in silence but slept separately in their own cells. A special court that dealt with youth crimes sent San Michele its inmates, an 18th Century judicial innovation by Clement XI, not picked up in America until the 20th Century.

- Ray Taylor, 15, jailed Nov. 12, 1914 on a charge of violating Section 920 of a penal law (Weapon?) that the record keeper's handwriting makes impossible to decipher for sure. Served 30 days. (Too light a sentence for most weapon convictions.) Listed as a "laborer" and able to "read and write." Page 182.

- A 15-year-old boy named Lloyd was among six people jailed on the same day (June 29, 1915) on the same charge (Burglary 3rd degree, Grand Larceny 3rd degree), two of the others having the same last name as his. But the outcome of the case was not entered in the ledger. Page 188.

- A 13-year-old girl whose first name was Lizzie and a 15-year-old boy whose first name was Albert were jailed on Oct. 4, 1915 -- each listed as a "Witness" -- and were released Oct. 6th. The nature of their cases or whether they were connected was not indicated. However they were jailed the same day as a 24 year-old married woman with Ruth as her first name was also jailed. She was charged with "Adultery." The two teenager and the young woman were the only entries of that date. Whether their cases were connected is unclear. Page 190.

- Two boys, Herman and Daniel, 15 and 14 respectively, both from Schenectady -- were jailed Sept. 27, 1917, as "runaways" and released the next day (presumably turned over to family or child agency representatives). Page 216.

- Charles, a 15-year-old "laborer" who could "read and write" and whose parents were entered as "dead" was jailed April 30, 1921 on a Burglary 3rd degree charge and released June 2 but it is unclear whether his month behind bars was a sentence served or a detention period awaiting trial after which he was released. Page 240.

- A 15-year-old whose first name was Elizabeth (but whose last name is difficult to decipher) was jailed Aug. 4, 1923, as "incorrigible." Because her name had two thin light line crisscrossing it, the webmaster has placed a dark red line through the last name on the image (not in the ledger page itself). Whether the thin crisscross lines were supposed to represent a "sealing" of the record is unclear. They certainly did nothing to render it unreadable. The record keeper's poor handwriting accomplished more in that direction than did the thin light crosscrossed lines.

Although her parents were listed as "both living," her "habits of life" noted as "Tem" (temperate) and she could "read and write," the initial entry of "school girl" was also crisscrossed.

Was that part of an ineffectual "sealing" of the record or indicative of her perhaps being more a truant than a student? On Aug. 17 - 13 days after she had been committed to the Elizabethtown jail -- Elizabeth was sent "to Hudson," a reformatory.

Opened in 1887 as a "house of refuge" for young women serving time for petty misdemeanors, Hudson became. In 1904, it became part of the juvenile justice system, housing girls aged 12-15.

Thus what had been the House of Refuge for Women at Hudson, N.Y., was renamed the State Training School for Girls and placed under the auspices of the state Department of Social Services. In addition to inmates convicted of petty crimes, many of the girls sent there fitted the category "incorrigible" in that they were found to have associated with known criminals or other bad companions, frequented taverns, dance halls, houses of prostitution, were habitual truants, refused to submit to their parents' proper supervision, or otherwise exhibited waywardness.

The kind of commitment criteria used in that era can be read the text of one 1910 version of the law involved in sending "incorrigible" girls to Hudson (see the image right from a legal notice in the Essex County Republican. Red underline added to web image for emphasis.).

The information entered for "incorrigible' Elizabeth on numbered Page 260 was the ledger's final record of an inmate under 16 years of age committed to the Elizabethtown Jail. The ledger entries for inmates ended on numbered Page 268.

How many, if any under-16-year-old inmate entries appear in the later ledgers is not known to this writer at this time. But the trend evident in this ledger -- for fewer and fewer such entries each succeeding year -- likely would have continued until they stopped altogether.

This informal survey of the approximately 45 under-16-year-olds among the more than 3,500 inmates whose entries appear on 268 of the ledger's pages does not reveal any labor or penal practices of the 1879-through-1924 period not previously known and covered by scholarly tomes.

Nevertheless, to see the names, ages, and notations concerning actual boys and girls who were incarcerated in the county jail makes the known historical features of the period come alive or at least seem more real than simply having a vague abstract awareness that children were so employed or so incarcerated in eras past.

Obviously, since only about 45 inmates among the more than 3,500 inmates in 45 years were under age 16, the ledger hardly evidences eagerness on the part of Essex authorities to lock up children in the county jail.

In fact, one suspects that some of those arrests came about only after the sheriff, his deputies or the local constables couldn't get the parents and the complainants to settle matters without resort to the county courts. In late 19th Century and early 20th Century rural communities of upstate New York, where most folks knew nearly all the other families thereabouts, people tended to be a bit reluctant to resort to having a boy or girl jailed. Having the parents punish the offender and/or make restitution would generally suffice.

Still, as a review of the ledger entries shows, some children -- even as young as 10 -- were jailed and more than a few served sentences in that jail or went off to reformatories, or even were sent to prison.

Perhaps, if classes from the local high schools visit the new jail, someone will point out that the old jail in decades past used to include among its inmates 10 to 15 year olds, but that, of course, the new jail does not and will not. At least, not unless current law undergoes radical revision. Of course, they should also be advised juvenile detention facilities do exist; they're just not called jails.

That's history: things change, things continue.

-- NYCHS webmaster

List of Links to Other Pages in New York Correction History Society's

Essex County Jail History Web Presentation

| |

| |

|