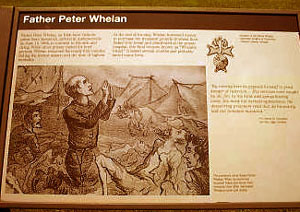

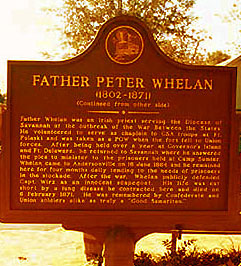

Chaplains are ranked officers and therefore Whelan was lodged with the other Confederate officers in a Fort Columbus barracks. But the priest spent most of his time with the enlisted men in damp, dark and dismal Castle Williams. The rebel prisoners there were in such desperate need for adequate food and clothing that he appealed to the pastor of the oldest Catholic church in New York State, St. Peter's on Barclay St. in Lower Manhattan, for help. The pastor, Fr. William Quinn, was most responsive, even writing federal authorities to parole Whelan to St. Peter's for the war's duration. Though Washington approved, Whelan again declined to leave the men. On June 20 when the Montgomery Guard officers were taken to Ohio for exchange, but Whelan also chose to stay with the enlisted troops. Finally, when these regulars were exchanged in August, the priest accepted release too. Once back in Savannah, Fr. Whelan resumed duties at the orphanage but was soon named chaplain for all Confederate forces in Georgia. Then in mid-June of 1864, having been asked to help out at Andersonville's POW camp for captured Union soldiers, Fr. Whelan was horrified to find 25,000 in a stockade built for 10,000. Daily Whelan remained at Andersonville stockade, from dawn to dusk, hearing confessions, comforting the sick, and ministering to the dying. When a lung ailment, probably tuberculosis contracted from the vermin-covered prisoners, finally forced Whelan to leave, he spent all his own money and borrowed more to buy bread for the starving Union POWs.

Pvt. Henry M. Davidson, 1st Ohio Light Artillery, writing home while at Andersonville, summed up the feelings of his fellow POWs about Whalen: By coming here he exposed himself to great danger of infection... His services were sought by all, for, in his kind and sympathizing looks, his meek but earnest appearance, the despairing prisoners read that all humanity had not forsaken mankind.

After the war ended, Castle Williams continued in use as a military prison. Among the more interesting prisoners held on Governors Island in the late 19th Century was a group of Chiricahua Apaches. The situation of some of them there so interested President Benjamin Harrison that he wrote on their behalf to appropriate officials from the Executive Mansion on Jan. 20, 1890:

The reports of General Crook and Lieutenant Howard, which accompany the letter of the Secretary, show that some of these Indians have rendered good service to the Government in the pursuit and capture of the murderous band that followed Natchez and Geronimo. It is a reproach that they should not in our treatment of them be distinguished from the cruel and bloody members of the tribe now confined with them. I earnestly recommend that provision be made by law for locating these Indians upon lands in the Indian Territory. President Harrison's letter referenced the Army's inclusion of General George Crook's scouts with other Apaches removed from the Western territories after the surrender of Geronimo to General Nelson A. Miles. Apparently done without benefit of military due process, the imprisonment of Gen. Cooks' Apache scouts -- who at the time were regular U.S. Army soldiers - was regarded by Crook and many others in and out of the military as dishonorable treatment by those in command of those who had served in the ranks. Risking oversimplification, here is a brief outline of the complex background: General Philip A. Sheridan was critical of Crook’s policies relating to pacification of Native American tribes. Crook was known for his vigorous and victorious military engagements against hostile Indians but also for his humane and honorable treatment of non-hostile Indians. By contrast, Sheridan's reputed actions toward Native Americans were such that a genocidal phrase attributed to him stuck to him, despite his repeated disavowals. The phrase may have stuck to him because it seemed -- unfairly or not -- to fit his alleged attitude, whether he said it in so many words: The only good Indian is a dead Indian.

One may suspect Sheridan expected and even wanted that to happen. He appointed General Nelson A. Miles as replacement. Miles immediately moved the Chiricahuas still on the reservation near Fort Apache to the railroad station at Holbrook, Arizona. According to John N. Morris, author of The Apache Conflict in and near Graham County, Arizona, "Three hundred eighty-two Indians, including almost all of Crook’s loyal Apache scouts were then loaded on a train bound for Fort Marion, Florida." The issue as it related to the imprisonment of the Apache scouts wasn't the good or bad judgment involved in Crook's extensive use of them. That could have been resolved without their imprisonment. No accounts of this chapter in American military history mention any charges ever filed against the Apache scout troopers, nor inquiries made, nor hearings held. They were simply interned with the other Apaches. That they were U.S. soldiers counted for naught. About a half century later U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry would be interned. Their U.S. citizenship would count for naught. That, in highly selective and compressed form, is the background to the removal of Army scouts and other Apaches from Arizona by Gen. Miles and their eventually becoming prisoners at Mount Vernon Barracks, Alabama, and at Governors Island, N.Y. Several weeks after Gen. Miles in the summer of 1886 summarily herded Gen. Crook's Army scouts in with their brother and sister Apaches being forcibly transported East - some eventually becoming Governors Island prisoners -- the Statue of Liberty was officially unveiled on Bedloe's Island, clearly visible from Castle William and Fort Columbus.

In one of those ironic twists that make researching history so interesting, Governors Island turns out also to have served as home circa 1893-1895 simultaneously to Generals Miles and O.O. Howard, the latter having helped call to President Harrison's attention the former's apparently unwarranted and unfortunate imprisonment of Crook's Apache scouts. Gen. Miles' stay on the island was certainly not as hard as that endured by the Apache prisoners but he may not have been the happiest of campers there either. He was known to have Presidential ambitions and from where he sat on Governors Island he could see those aspirations going nowhere.

The last of the surviving Chiricahuas Apaches removed by Gen. Miles were released in 1914 -- after 28 years as U.S. prisoners of war! Their discharge came 11 years after the poem The New Colossus, engraved into a small bronze plaque, was placed on one of the interior walls of the Statue of Liberty pedestal as a memorial to Emma Lazarus who had written it in 1883 fo help raise funds for the support structure. Aside from family, friends and some admirers among the literati, the sonnet drew little attention at the fund-raiser. It was not even mentioned at the statue's official unveiling three years later. The plaque project wasn't formally initiated by its prime mover, Emma's friend Georgina Schuyler, until 1901, about 16 years after Lazarus' death at age 38. The languishing of the Chiricahuas in Governors Island prison included several of those years that the Lazarus poem languished in obscurity predating the plaque. Nor did the plaque immediately lift it from obscurity. The Liberty statue and the plaque's poem linkage in the public mind did not even begin to take shape until decades later as advocates and foes of immigation regulations both started quoting from it to make their opposing points:

Whether any Native-Americans imprisoned on Governors Island, with its splendid view of Liberty Island, had ever indicated awareness of the lofty words written for the statue dedicated during the first year of their captivity is not known. But the poem's seemingly exclusive concern with the plight of immigrants -- some interpretations see its focus as chiefly on urban Europeans -- has not been lost among succeding generations of native peoples concerned with their own plight in their own land. Even before his forcing Gen. Crook's transfer, Gen. Sheridan had been involved in a somewhat similar situation with another general -- Gouverneur Kemble Warren of Cold Spring, N.Y. Given the North's numerical superiority, Grant and Sheridan are portrayed as pursuing a war of attrition, consistently initating offensive military action despite likelihood of massive Union casualities greater than those sustained by the Confederate forces. In contrast, Warren tended to reserve initiating attacks for situations where the prospect of victory came into closer balance with the causalities that would have to be paid to achieve it. The opportunity for Sheridan, with Grant's backing, to remove Warren from field command came when the New Yorker delayed moving troops as ordered at Five Forks in the spring of 1865. Warren maintained the delay had arisen from his having received conflicting orders that required time to sort out.

A West Point-trained engineer, he handled major military engineering projects during the post-war years, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Nevertheless, he pressed to clear his name of the cloud cast over it by his removal from field command. President Hayes in 1879 ordered a Court of Inquiry that convened in January 1880 on Governors Island and closed in July 1881 to consider a verdict. The judgment exonerating Warren came in November 1882 two months after he had died at age 52 from a diabetes-related illness. |

Click red-letter page number in top frame above or here below to access that page:

|

|

| |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| To Civil War & Correction menu. | ||

© NYCHS reserves and retains all rights to the text other than quoted excerpts. Non-commercial educational use permitted provided NYCHS and/or its web site -- www.correctionhistory.org -- credited as the source.

© NYCHS reserves and retains all rights to the text other than quoted excerpts. Non-commercial educational use permitted provided NYCHS and/or its web site -- www.correctionhistory.org -- credited as the source.

Associate Professor Jannelle Warren-Findley of the Department of History of Arizona State University is researching Governors Island's history for a National Park Service project. Information sent to webmaster@correctionhistory.org that might be helpful to her research will be forwarded to her. Or send the information directly to the e-mail address listed on her Arizona State University Dept. of History faculty page. See Page 6 for listing and links of the scores of on-line sources of Governors Island information and images used in this presentation. --- Tom McCarthy |