|

Antecedent: Preceding in Time, an Ancestor

The New York City/County Public Charities and Correction's nautical school and its training ship Mercury, based on Hart Island in Long Island Sound 1869 - 1876, played an antecedent role in the origins of the State University of New York Maritime College at Fort Schuyler, also on the Sound.

They were "antecedent" not only in the sense of preceding in time (by 5 years) the New York City Board of Education's nautical school from which the college evolved, but also in the sense of ancestral relation.

In terms of preceding time-wise, the reformatory ship school, launched in 1869, was the first maritime training institution authorized with funding mandated by the state Legislature as well as the first actually funded by New York City/County and its Board of Education.

In terms of ancestral relation, the reformatory ship school's legislative authorization and initial state mandate for funding reflected the legislators' intent to foster the training of young New Yorkers for employment and service in the maritime industry so important to the economic vitality of the state.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above image is derived from a digital photo of the interior court or open area -- grass, walks and flag pole -- at old stone Fort Schuyler on the SUNY Maritime College campus beneath the Throggs Neck Bridge that spans Long Island Sound. Taken July 17, 2009, by the NYCHS webmaster during a visit to the campus museum, the view faces toward the museum entrance on the far side from the flag pole. He stood under a "St. Mary's Pentagon" sign when taking the picture. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | |

This public policy intent is the DNA linking the Hart Island nautical school to the Board of Education nautical school and, therefore, to the maritime college as well.

This Part 8 page -- citing facts laid out in Parts 1 through 7 -- argues the case for that antecedent role receiving acknowledgment due an ancestor-pioneer in New York maritime training:

- perhaps a footnote, or other modest addendum in future official retellings of SUNY Maritime College's history on the web, and

- perhaps a small framed illustration of the Mercury, with an explanatory caption, displayed in the campus museum's Training Ship Wing.

The Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler is a treasure trove of merchant marine artifacts and information telling the history of seafaring from the days of the ancient Phoenicians to the current era. Situated within the old stone fort standing guard over the Long Island Sound entrance to the East River, it is a jewel of a museum in a beautiful setting. One could spend not just hours, but days viewing its collection on display. It is well worth a visit by anyone interested in New York history, which cannot be understood properly without reference to maritime commerce.

The Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing features all eight of the school’s training ships. The wing is named for Class of 1947 alumnus and maritime historian Captain Joe R. Gerson who was an honorary director of the Maritime Industry Museum and one of its founders. He died in the early fall of 2005.

From a New York correctional history perspective, there apparently is an unfortunate omission in the museum's presentation of that history. No reference to the Hart Island nautical school and its training ship Mercury is readily visible among the exhibits and displays in its Training Ship Wing.

Likewise, a similar silence is observed in the historical training ships narrative on the college website in the section set aside for the museum. That dates its story of training ships from the 1874 arrival of the NYC Board of Education's New York Nautical School ship St. Mary's:

|

. . . . . . . . training America's sailors has changed since the school's and America's first merchant training ship went into service in 1874.

|

Not so much as a passing mention is discernable regarding NYS and NYC's first merchant training ship Mercury that preceded the St. Mary's by five years and that continued its classes and cruises a sixth year after the latter's arrival.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

The NYCHS webmaster stood beneath the "St. Mary's Pentagon" sign that is seen in the above image when this image series' first photo was taken of the old ford's open interior court, looking to the museum entrance on the far side of the center flag pole.Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | |

Yes, for about a year, New York City had two nautical training ships, operated by different agencies of its government (the Board of Education and the board of Charities and Correction Commissioners), both vessels making news with their all-sail cruises to points beyond New York Harbor and Long Island Sound, their junior mariners high up in the masts and rigging.

On May 5, 1875, in the same multi-item column headed "City and Suburban News," the New York Times reported

- that the St. Mary's would remain a few days longer at the foot of East 23rd St. before being towed to an anchorage off the Battery, there to await sailing orders "issued by the Board of Education," and

- that the "School-ship Mercury of the Department of Charities and Correction" was expected to arrive in port the 15th of the month, whereupon efforts would be made to place with ship lines those boys competent to be seamen and place others with the Navy as trainees.

Long History of Not Acknowledging Mercury

Non-acknowledgment of the Mercury has a long history itself, with roots in the efforts by the NYC Board of Education to disassociate, in the public's mind, the St. Mary's and the Newport from that reformatory-with-sails.

The reform school ship was like the ancestor whom someone with upwardly mobile ambitions might wish wasn't related and might wish others would forget that he was.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Engraved brass plate attached to entrance door announces "Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler." Image is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | |

Parts 6 and 7 cite, in more detail than here, five separate occasions when allusions -- some subtle, some blunt -- were made to St. Mary's/Newport/Mercury association in the minds of some of the public, an mental linkage that evidently persisted despite the very real distinctions in the managing agencies involved and in the backgrounds of their student crew enrollments.

Probably additional examples could be found, but these five should suffice to establish the point:

-

William Henry Rideing's opening line of reassurance in the concluding paragraph of an 1878 article about "The Boy Who Wants to be a Sailor" in Scribner's Monthly:

|

The boys of the St. Mary's belong to a respectable class and a good moral tone prevails among them. . . .

|

- St. Mary's Class of 1877 alumnus John C. Hatzel's comments to the New York Times (NYT) Feb. 8, 1906, explaining why he designed a "new look" for the New York Nautical School student uniform:

|

People, generally speaking, always connect the schoolship St. Mary's with a reformatory. A way back in the '60s, when the Mercury was then in use, it was a sort of a reformatory, but that has all passed away.

|

- The NYT report about the announcement at commencement exercises Sept. 22, 1908 by Board of Education president Egerton L. Winthrop that

|

. . . . . . . . the Newport should no more be known as "school ship," implying that it was a place for bad boys, but that it should be known as a "training ship," which fitted New York boys for an honorable career on the sea.

|

- The first paragraph sentences of a June 2, 1912 NYT report about a Newport cruise to England:

|

. . . . It is at present the plan of the Board of education to make this the last cruise of the schoolship. . . . The school has on it at present seventy cadets of good families . . . .

|

The "of good families" phrase was intended to dispel any lingering impression some readers still might have had that this was the sailing reformatory from four decades earlier.

- The subheads over the NYT Jan. 23, 1913 Board of Education story about its abolishing the nautical school:

|

SCHOOLSHIP TO BE GIVEN UP

High Cost of Maintenance and Fact

That Parents Regard It as a

Reformatory the Reasons.

|

St. Mary's Boys Came From 'Good Families'

|

XXX

XXX |

|

A ship's wheel and lighthouse stairs appear directly ahead upon entering the maritime college campus museum. Bearing to the right takes the visitor toward the Training Ship Wing entrance near a 1776 map (in above image, the further right map ) of Frog's Neck, the name back then for the area where now the campus is situated. Image is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | The school board members had legitimate grounds for wanting the public to view their nautical school and its ships as separate and distinct from -- not a continuation of -- the Charities and Correction agency's reform school ship.

Despite some similarities in the two NY nautical training programs, the differences were substantial.

The Board of Education school ships' cadet crews quite probably did consist of boys from "good families," if that phrase is understood in minimalist terms.

The public school boys were more likely than the reformatory boys to come from at least identifiable families, with fixed abodes, and one or more members lawfully employed. Parental consent forms had to be signed for enrollment in the school board's nautical training program. The family had to pay a modest one-time fee for the student's uniform. Signed testimonials to the applicant's "good character" had to accompany the application.

The "good families" or "respectable class" phrase, used in the school board ship context, was a way of underlining the contrast of its boys' backgrounds to that of the reformatory ship boys. The contrast could hardly have been any greater.

Reform School Ship Crews Quite a Contrast

For their Hart Island industrial school, from which developed their nautical school, the Public Charities and Correction Commissioners had targeted quite a different enrollment pool than "boys from good families."

As quoted in this web presentation's Part 2, the commissioners described that youth target to the state Legislature in 1868:

|

. . . there are 30,000 children in this city growing up in ignorance and idleness. They have no occupation but to beg and learn no art but to steal. Hordes of children are sent out every morning to beg or to pilfer along the piers and bulkheads of the city . . .

their progress from the first act of pilfering to burglary is as regular as the progress of a school boy from class to class.

At the age of 15 . . . the boys [have become] professed thieves. . . . dispers[ing] this portentous evil can only be accomplished by rescuing the children at a tender age, and before they have entered on criminal or immoral practices.

To this end it is respectfully recommended that the Board may be authorized to establish an Industrial School . . . .

|

'Good Boys Boat' vs. 'Reformatory Rig'

|

XXX

XXX |

|

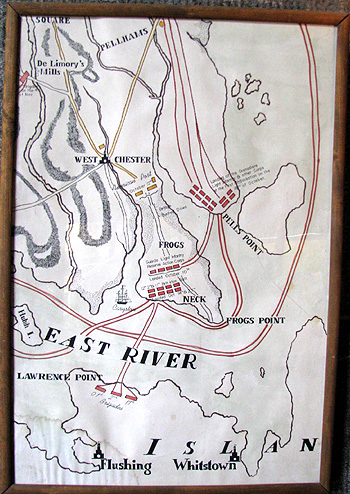

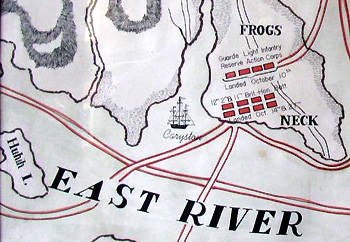

The visitor bearing right from the museun entry area passes on the left a map depicting British Gen. Howe's October 1776 attempt to have his forces penetrate Gen. Washington's defenses in Westchester by landing Red Coats and Hessian mercenaries at Frog's Neck, the name for the area now known as Throggs Neck. Howe's forces were repelled.

The sailing ship depicted on the map apparently was the Carrysfort, a 28 gun-frigate, one of the command vessels involved in Howe's operation.

Above is an image of the full framed map. Below is a detail section showing an island west of Frog's Neck in the same general area where Rikers Island is situated, except this island bears the map designation "Huhih I." However, that may be a spelling corruption of Hulet, Hewlett or Hallett for the family associated with island before the Rikers. Click either image to access, elsewhere on this website, pages from Edgar Alan Nutt's The Rikers where he discusses the Hewlett connection.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

| This web presentation's Parts 1 and 2 explore the several and varied antecedents to New York's school ships. From that mix emerged, before the Civil War, two competing models which NYers could consider for training youths to become seamen.

They were what might be tagged, tongue in cheek, the "good boys boat" versus the "reformatory rig."

Baltimore in 1857 and Charleston, S.C., in 1859 led the way with ship schools for boys of "good character."

Massachusetts led in the other direction with its reform school ship launching in June 1860.

The New York Chamber of Commerce, a leading advocate of nautical training for "honest boys," succeeded in getting the state Legislature to authorize establishment of such a school under its control, provided the organization raised sufficient funds by subscription.

During the national conflict, the project never advanced beyond words on paper.

After the war, the Chamber renewed its campaign for an "honest boys" nautical school under its direction. But this time the plan proposed involving the Board of Education.

Meanwhile, in February of 1867 the managers of the House of Refuge, operated on Randalls Island by the Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquency, asked the Legislature to establish under their control a nautical training ship program of "discipline and instruction."

Their request came on the heels of a report to legislators in Albany by the top officers of the state's leading penal organization, the Prison Association of New York (PANY), urging a reform school ship nautical training program. PANY leaders cited how older House of Refuge boys who enlisted in the military during the war had acquitted themselves well.

The report's authors, Enoch Cobb Wines and Theodore W. Dwight, asked rhetorically:

|

Why should they not pass through a reformatory school-ship, and thence into the merchant service, or, indeed, into the navy, and acquit themselves well?

|

As C of C, House of Refuge Face Off, PC&C Enters

Onto the scene of this face-off between two high-profile, politically-connected organizations -- the Chamber of Commerce and the House of Refuge, each seeking legislative action for establishment of a nautical training program of its own -- entered the even higher-profile and even more politically-connected Commissioners of NY City/County's Public Charities and Corrections (PC&C).

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Beyond the "Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing" sign and to the left of the blank wall in the center of the image above is the very excellently-executed exhibit on the St. Mary's and Newport. That blank wall returns later in this series of images derived from digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009 visit to the Maritime Industry Museum at Ford Schuyler. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | Given the massive sweep of PC&C activities, the sheer numbers of people involved in and impacted by those activities, the huge expenditures under the Commissioners' control, their board was a power in itself, and often unto itself.

Additionally, by the vagaries of the spinning wheels within wheels of politics and government, this particular PC&C board just happened to be one of the strongest in New York history.

The board was evenly balanced: two Democrats and two Republicans. Rather than that arrangement resulting in stalemate and paralysis, it seemed to foster a non-partisan or bi-partisan united front approach which only served to make the board even more formidable.

Part 2 details how each PC&C Commissioner was a political dynamo in his own right -- particularly the "Robert Moses" of his era, Democrat Isaac Bell and Republican Gen. James Bowen, the highly-respected former Police Commissioner.

Part 2 also details how each of the four had a real connection and feel for NY as the country's No. 1 port and harbor city.

PC&C 4 Shared Regard for City as a Port

Perhaps their shared personal regard for NYC as a port of entry and of commerce bound them together, not just on the nautical school project, but other PC&C programs as well, over-riding and dispensing with partisan politics that prevailed elsewhere in New York government.

Not only did the PC&C Commissioners win legislative authorization to set up the nautical training ship as a kind of annex to their Hart Island industrial school, they also obtained mandated funding for it. Separate from that state mandate for city funding of the seamanship school, they even arranged for the Board of Education to pay the salaries of the ship's teachers of academic subjects.

The Commissioners didn't have to go the Navy to beg loan of a vessel for training purposes. Bell, a shipping line top executive, was in position to readily facilitate acquisition of a Havre packet and crew.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

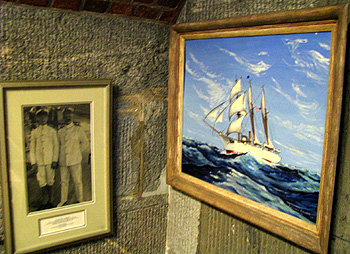

On the left-hand wall, as the visitor walks from the museum entry area to the section immediately below the the "Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing" sign, is a photo of Joe Gerson from his days aboard as a member of the Class of '47. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | When a replacement skipper was needed, Bowen -- credited with being the initiator of the PC&C nautical project -- likely also initiated contacting Capt. Pierre Giraud, one of the Union Naval heroes in the Gulf region over which the general had served as military administrator.

Mercury's Finest Hour: Trans-Atlantic Soundings

Gen. Bowen possibly also had been initiator of what must count as the school ship Mercury's finest hour: its

2,800 miles of tropical Atlantic deep sea soundings between Sierra Leone and the island of Barbados for a scientific study involving the United States Costal Survey and New York University Dr. Henry Draper. Part 3 describes it.

A medical doctor with various scientific interests, Draper had built an astronomic observatory on his family estate in Hastings-on-Hudson, which was also Bowen's home village. The doctor, much celebrated for his scientific contributions, would also have been known to Bowen and the other PC&C Commissioners as a physician at Bellevue, one of the agency's several hospitals.

Even in praising how well the 250 student mariners aboard the Mercury had handled their duties on that long cruise, in calm seas and foul, the New York Times Dec. 8, 1871 editorial noted the "school-ship reformatory experiment" had been instituted by PC&C board members to deal with

|

considerable numbers of wild, reckless and semi-criminal lads . . . consigned to them by the Courts, or sent to them by parents unable to control their children.

|

While the PC&C Commissioners had been able to use their political muscle to push their school ship plan through the Legislature, obtain state-mandated city funding and unmandated Board of Education funding, get the program up and sailing in short order, they seemed unable to solve its three basic defects:

- the non-voluntary nature of its students' participation,

- the indeterminate nature of the student's stays in the program, and

- the evident lack of willingness by the maritime industry to help supplement the training of the reformatory students or to hire them after graduation.

Issue One of Trust and Class, not Skill

|

XXX

XXX |

|

A group of sketches of training ship scenes appear on the right-hand wall, as the visitor walks from the museum entry area to the section immediately below the the "Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing" sign and opposite the photo of Joe Gerson from his days aboard as a member of the Class of '47. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | Not surprisingly, the Chamber of Commerce -- having been out-maneuvered in the state Legislature by the PC&C -- showed little interest in helping the Mercury succeed. At least, research so far has not found any evidence in that direction.

After all, why should the major organization representing ship owners, shippers, insurers and sundry other professions involved in port commerce have assisted the reform school ship?

Had not Brig. Gen. Edward Leslie Molineaux stated their concerns quite accurately in December 1866 (as quoted in this presentation's Part 1) when he wrote on behalf establishing a school ship under the Board of Education?

Had he not explained that, while a reformatory ship might make excellent sailors "out of vicious boys," the shipowners sought nautical training for "a better class (not juvenile delinquents)" to whom they could entrust their vessels?

In brief, they wouldn't and didn't trust their ships and their cargoes to reformatory school ship graduates no matter how well-trained in matters nautical. The issue wasn't skill. The issue was one of trust and class.

Nativism, anti-Irish, anti-Catholic Threads

Parts 1, 4 and 5 touch upon nativist, anti-Catholic and anti-Irish elements in the drive to educate "native Americans" to man the country's merchant ships as well as in the drive for political reform that toppled the Tweed Ring. These are not the whole story, but they are discernable aspects appearing and reappearing in it, like identifable threads woven throughout a fabric.

Obviously, the young nation had good and sufficient objective reasons to want its fledgling maritime industry not to be dependent on the nationals of other countries to sail its merchant vessels and handle their cargos. Nevertheless, some of the sentiments voiced in public on behalf of that cause reflected antipathy to the recently arrived foreign-born, not only to seafaring nationals of other countries who made their homes elsewhere than America.

Even the adroitly-phrased pamphlet, Remarks on the Scarcity of American Seamen; and the Remedy, by a "Gentleman Connected With the New York Press," resorted to negative stereotypes. He did so in disparaging foreign-born seaman and distinguishing them from immigrants who settled in America to live, work and raise their families in their new country.

|

Not so the foreign sailor—he is a creature of impulse and of most frightfully erratic habits! He is tied to no particular spot, nor in fact to any particular person:

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Sketch captioned "Impressing American sailors" appears in Chapter XI of Dewey

And Other

Naval Commanders

by Edward S. Ellis, published by Hurst & Company, NY, 1899, and made available through the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation. The chapter touches upon Royal Navy press gang impressments as a cause of the War of 1812. Click image to access. Use browser's "back" button to return. | | "In every port a sweetheart finds,"

He has generally—almost universally, no kindred here—no tie—nothing to bind him to our soil—no stake in the country. . . . . How then can he love our land, or love our flag—sufficiently to shed his blood in its defence?

Again, a most objectionable feature against foreign sailors, particularly against the large number of Englishmen now in our merchant service, is, that they are always claimed by their own government, when needed, and are taken out of our ships sans cérémonie, on plea that "once a British subject, always a British subject!"

|

Since the Irish were regarded by Royal Navy press gangs as British subjects, the pamphlet's rhetoric, in effect, offered a not-so-subtle justification for avoding inclusion of Irish among one's crew members.

The little booklet closed with a petition to Congress for restoration and explansion of a Naval Apprenticeship System. The most celebrated name among the petitioners was former Mayor Philip Hone's. His diaries, now highly valued as historical resources, are replete with anti-Irish and nativist sentiment.

Perhaps appropriately, the year of the pamphet and petition's publication -- 1845 -- the mayoral candidate of the nativist, anti-immigrant American Republican party [not related to Lincoln's Republican party] won election: James Harper, printer and publisher.

His publishing house, particularly Harpers Weekly with its virulent anti-Irish and anti-Catholic cartoons drawn by Thomas Nast, figured significantly in the rise of the political reform movement that brought down Boss Tweed.

Council of Political Reform key leader Dexter Arnold Hawkins, as detailed in Part 5a, was given to gratuitous attacks upon the Catholic Church. His fellow Cooper Union "save-our-common-schhols" rally dignitary, the Hon. Wm. Laimbeer, in a prepared address later reprinted in the Times), managed to turn the public policy question of state aid to non-public schoola into a partisan combined political and secretarian attack:

|

The time may come when unscrupulous politicians, to secure political influence of the Jesuitical power, may combine to deprive us of our schools . . . .

|

The Honorable William Laimbeer, as PC&C Commissioner, sought to get rid of the Mercury and was instrumental in getting its chief sponsor, Gen. Bowen off the board.(See Part 5b.)

The state legislator whom the Chamber of Commerce singled out for particular praise after passage of public school ship bill it championed was Republican Assemblyman James W. Husted, who had begun his political career as a candidate of the anti-immigrant, anti-Irish and anti-Catholic Know Nothings aka American Party. Husted bill set up the New York Nautical School to be run by the NYC Board of Education, with in-put from a Chamber-appointed Council of Advisors representing the NY maritime industry. The school board and the chamber arranged with Gov. Dix to ask the Navy Secretary George Maxwell Robeson for a vessel to use as a nautical school ship, under a federal program to the promote maritime training.

Mercury Crew Turnover Problem Cited by Skippers

As this presentation's Part 5 quotes in detail, Mercury Captains Pierre Giraud and F. F. Gregory in their submissions for the PC&C Commissioners' annual reports, respectively 1870 and 1875, called attention to the disruptive impact on the program by the constant turnover of students before completion of training. The skippers argued that if the students knew they had to stick with the program a fixed length of time or until their seamanship skills met a certain measurable standard, they would focus better on completing the training, instead of seeking early discharge.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

The school ships St. Mary's and Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing. Image is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | Had some degree of volition been involved in the students joining the program, their attitude might have been a bit more accepting of its rigors. Many correctional systems offer some inmates intensive training programs with the incentive of early release upon successful completion. If some variation of that could have been devised for the school ship crew, perhaps enrollment turnover and "desertions" would have declined.

But even if the PC&C Commissioners had found a way to get its Hart Island industrial school students to sign onto the Mercury "voluntarily" and had found a way to have the courts set longer, more fixed terms for the youths committed to their custody, the lack of support from most of the maritime business community would still have remained as a fatal flaw.

Had that community backed the project, participated in perfecting it and hired more of its graduates, NYC politicians involved in keeping the very expensive program afloat would, more likely than not, have continued approving adequate municipal budget appropriations.

Chamber Waited for Right Moment to Make Move

Instead, the Chamber of Commerce apparently bided its time and waited for a propitious opening to foster launching a school ship program structured more to its liking; that is, aimed at recruiting "honest boys" and subject to in-put from the Chamber.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Image of a St. Mary's photo (circa 1904 at Glen Cove) displayed in the school ships St. Mary's and Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing. Image is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. TClick image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | The Panic of 1873 and the ascending of Republican James W. Husted that year to chairmanship of the Assembly Education Committee provided just such an opening. How that played out is covered in Parts 4 and 5.

Once the state mandated the city to fund the school board's nautical training ship, the Hart Island reform school ship was doomed. The city wasn't going to pay for two maritime instruction vessels.

Should recognition as a Fort Schuyler Maritime College historical antecedent be withheld from the Hart Island nautical school and ship - because the PC&C project's defects proved fatal and

- because the Board of Education nautical school rejected being associated with it in the public mind?

If the fact that a nautical school's defects eventually proved fatal is to be the criteria for not recognizing its role in the maritime college's history, then should not acknowledgment of the Board of Education nautical school's role also be withheld? Likewise, should not that school's founding date of 1874 be abandoned as the offcial starting date for the college's history?

Maritime College History Start Date: 1874 or 1913?

The name of the Board of Education institution authorized by legislative act in 1873 and implemented in 1874 was the New York Nautical School. That institution, bearing that name, died Oct. 31, 1913. This presentation's Parts 6 and 7 spell out the critical defects leading to its demise.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Image of a photo on display in the school ships St. Mary's and Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing. The caption beneath it reads in part: At Recreational Pier, Foot of East 24th Street, New York City, April 1904. Image is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. The blur in the center of the digital image resulted from window light reflecting on the glass covering the original 1904 framed photo. Despite the digital image's defect, it is used here because it is based on one of the few that show the ship at its East River "home."Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | Chapter 332 of the Laws of 1913 established a New York State Nautical School (emphasis added), contingent upon the discontinuance by the NYC Board of Education of its New York Nautical School.

In other words, NYC school board's nautical program had to die first before the state's nautical program could be born. The latter was not a continuation of the former. Designated successor, yes; clone or reincarnation, no.

Undoubtedly the 1913 legislation's intent with respect to the school board's nautical training program, was -- as its opening declared -- "to perpetuate and insure the continuance of that institution and to extend its privileges to young men throughout this state."

But despite the officially stated intent, the actual instrumentality devised was quite a different entity than the one the law claimed it sought to perpetuate and continue. The new-born school was distinct, separate, and unique in its governance, funding, scope, administrators, teachers, name, and student selection process. Only the ship and the port were the same.

While arguably, from a narrow technical perspective, the 1913-founded New York State Nautical School was not a continuation of the 1874-founded New York Nautical School, it was clearly the designated successor institution.

Fatal Flaws of Bd. of Ed.'s NY Nautical School

The demise of the NYC Board of Education-run nautical school due to its defects ought not deny it proper recognition as the state training maritime institution's predecessor. Not any more than the demise of the PC&C Hart Island nautical school, due to its defects, ought deny it appropriate acknowledgment as an antecedent to the school board's nautical program.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Image above is based on a companion photo to the one showing the St. Mary's at the East 24th Street pier in April 1904. The image shows a view on board the school ship during rough weather. It is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | Both NYC nautical school projects were fatally flawed, but despite that, both deserve their place in the maritime college's history.

Chief among the NYC Board of Education nautical school's fatal flaws were

- the unfunded nature of the state Legislature's mandate that the NYC Board of Education run it and the city/county finance it;

- the tensions between the public school educators' approach in running it and the way that the Chamber wanted it run;

- the decreasing involvement of the Chamber generally, except in the singularly united front campaign to obtain a replacement ship for the St. Mary's and,

- the training ship's declining enrollment from the city's public schools.

Fewer than five years after the St. Mary's 1874 arrival, all members of the school board's committee on economizing recommended asking the Legislature to rescind the requirement that the city education system operate and maintain the nautical program.

The nation's master shipbuilder of that era, William Henry Webb, founder of the Webb Institute for naval architecture, signed off on a report highly critical of the state-mandated program being part of the city public school system.

An additional decade of the city school board running the seamanship training program did not erase discontent about it. School board president J. Edward Simmons called it an "expensive and not altogether successful" experiment. Mayor William R. Grace was blunter. To His Honor, it was a mere pet of a few people but "one of those things we can't wipe out."

Chamber Changed Mind on Bd. of Ed. Ship Role

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Image of a framed St. Mary's painting and a ship's wheel, on display in the school ships St. Mary's and Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing, is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | A little more than a decade and half after having helped sink the Hart Island nautical school program by backing establishment of the state-mandated NYC school board-run maritime training program (with some Chamber in-put), that business organization sought to have the board walk the blank, so to speak.

The Chamber wanted the program's management transferred from the Board of Education "to the ship-owning interests of this port."

In a 1890-91 report to the state education commissioner, the Chamber complained that the city school board had failed to heed the port business community's advice on important aspects of program and, as a consequence, had limited its usefulness.

Chamber members spoke of withdrawing from any connection with the program and of having the Legislature relieve the organization of the obligation to appoint an advisory council to the school.

1st State Ship School KO'd, 2nd OK'd

The lamentations of the Chamber, mayors, sundry other office holders, municipal budget cutters and school board members about the state-mandated NYC ship school culminated in 1893 passage of legislation to transfer it to the state.

But Gov. Roswell P. Flower vetoed the bill, basically saying the state already had enough things on its plate without taking on any more projects.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Image of a scale model of the St. Mary's that is on display near the school ships St. Mary's and Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing, is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | The deteriorating condition of the St. Mary's helped bring together and energize city and school board officials, the Chamber and other port business community leaders, and the school's emerging alumni association in a successful united campaign to obtain a replacement vessel equipped for steam as well as sail.

But their 1907 victory in having the Navy transfer the gunboat Newport to the school did not end their efforts -- sometimes separate, sometimes united -- to have to the mandated city nautical school transferred to the state.

As described in Part 7, they finally achieved that in 1913 with a beautifully orchestrated and choreographed death-and-transfiguration political and governmental ballet.

The city's New York Nautical School gracefully terminated itself on cue but set free its spirit to float through the mist and descend upon the New York State Nautical School, waiting in the wings to emerge and be born.

Purists' Start Date for Maritime College Rejected

SUNY Maritime College prefers to use as its own the New York Nautical School's birth year of 1874, not the New York State Nautical School's birth year of 1913.

Purists might argue that the college can do that - only by viewing the official demise of the school board-run nautical institution in 1913 as a mere legal fiction that was necessary to facilitate rebirth as a state school, and

- only by ignoring that the state entity thus brought into existence was not the same old school with a slightly different new name, but basically a different institution, except for the ship and the port.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

The image above is of a panel of deck scenes aboard the St. Mary's during the cruise of 1903. The panel is on display in the school ships St. Mary's and Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing. The panel image is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum.

The image below is based on one of the 1903 photos in the panel. It is captioned "Making Fast."Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. |

|

XXX

XXX |

| This web presentation does not adopt the narrow puristic interpretation.

The 1874 starting date for the college's official history is not challenged here but embraced. So is the understanding that the continuity of purpose

- in the Legislature's mandating establishment of the school board-run nautical training program and

- in the Legislature's much later establishing the state-run nautical training program

binds the two together in history.

That state legislative purpose was to promote and provide seamanship training for New York youths to pursue careers of honorable service in New York's maritime commerce.

Legislative Purpose Continuity Kin Ship Key

Not a particular ship, nor a particular management agency, nor a particular institutional structure, nor a particular student enrollment pool determines continuity in New York's maritime training history.

The abiding and continuing intent informing the Legislature's action in establishing this or that form of seamanship schooling, in this or that era, provides the kinship or bloodline connecting them all as family.

But this rubric also extends inclusion in the family to Public Charities and Correction's Hart Island nautical school and its ship Mercury.

New York State legislators both authorized and mandated funding for that earlier nautical training program, having among their purposes for doing so the same intent as in establishing the two later programs. The Legislature didn't mandate NYC's county board of supervisors to provide $40,000 for the PC&C Commissioners to establish any industrial school extension they deemed appropriate. Nor was that money for a dry-land teaching of nautical subjects.

Three little words established the legislative intent: "nautical school ship."

As this presentation's Parts 1 and 2 detail, informed New Yorkers were no strangers to the general concept which that three-word term designated, or to the rival approaches under its heading. They were aware competing models were being promoted as alternative ways to interest American youths in, and train them for seafaring careers, thereby making the country less dependent on foreign nationals to man American vessels. Perhaps recent arrivals in New York may have been unfamiliar with the issue but certainly the veteran lawmakers in Albany were conversant with it.

By placing "under the direction of Commissioners of Charities and Correction" the "nautical school ship" that NYC's county board was being mandated to fund, the NYS Legislature made clear on May 12, 1869, its intent to give the reform school seamanship training approach a try.

That the Hart Island program also involved a reformatory purpose did not negate the fact of a legislative intent to promote and provide training for New York youths to pursue careers of honorable service in New York's maritime commerce.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

The image above is from the panel of deck scenes aboard the St. Mary's during the cruise of 1903. The scene is entitled "Hoisting #1 Cutter." The panel is on display in the school ships St. Mary's and Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing. The panel image is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum.

The image below is based on one of the panel photos. It is captioned "Looking Forward on Spar Deck."Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. |

|

XXX

XXX |

| The legislators, like the PC&C Commissioners, reasoned the two purposes were not contradictory, but could be complementary; that, by training the reformatory boys in seamanship, the school ship would both provide the skills for the youths to make honest livelihoods and provide New York's maritime commerce with trained mariners.

Something Else at Play in Mercury Rejection?

Yes, the reformatory nautical school failed to overcome its defects and died.

But logically that fact should no more exclude it from the maritime college's "family history" than should the Board of Education nautical school be excluded because it too failed to overcome its defects and died.

Both had fatal flaws but both belong in the maritime college's "family album." At least, logic would seem to suggest so.

But perhaps something other than logic is at play in perpetuating into the 21st Century the efforts undertaken in the later 19th and early 20th Centuries to disassociate the Board of Education's nautical training program from the reformatory nautical school.

Those efforts to distance in the public's mind the St. Mary's and Newport from the Mercury made some sort of sense back when the school board's program was in jeopardy, in part because of the misconception that the school board ships were continuations of the reform school ship.

Thus stress was placed on their cadet crews consisting of "boys of good character," all sons of "good families."

That emphasis was meant to contrast with the earlier ship's student crews drawn from the Hart Island industrial school of street urchins, "vicious boys" and "semi-criminal lads."

The Board of Education wanted known that its nautical trainees were of "the better class," the kind of "honest boys" to whom Gen. Molineaux said the shipowners felt they could entrust their ships and cargo.

Mercury's Dead End Kids Not 'Better Class'

The first quotation on this page were the words of 1877 St. Mary's alumnus John C. Hatzel who said in 1906,

|

People, generally speaking, always connect the schoolship St. Mary's with a reformatory. A way back in the '60s, when the Mercury was then in use, it was a sort of a reformatory, but that has all passed away.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Image of the Newport side of the school ships St. Mary's and Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing. It is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | But indeed has that "all passed away" or is the present day non-recognition of the Mercury's antecedent role in the origins of the maritime college a continuing attempt to exorcize the Ghost of Reform School Ship Past?

More than 133 years have come and gone since Mercury's sails last bellowed in the breezes on Long Island Sound and its Dead End kids climbed its masts and walked its rigging in their grubby Navy uniform knock-offs.

They definitely weren't of "the better class" to get invited to social upper crust lawn parties along either shore of the Sound; not then and probably not even now (were time travel possible for sailing ships).

Grimy Gamins' Ship Got Into Record Book First

Yet, after a century and a third, hasn't the time finally arrived to acknowledge the kinship of their nautical school and their training vessel in the "family history" of State University of New York Maritime College?

Is it not, at long last, time to give due recognition to the Mercury as the first nautical training ship authorized with funding mandated by New York State and also the first actually funded by New York City and its Board of Education?

The New York State Nautical School, from which the maritime college is a clearly defined lineal descendent, was the state's third serious attempt at nautical training.

The NYC Board of Education-run NY Nautical School was the second attempt.

The Public Charities and Correction program, based on Hart Island, was the first. That's the record.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Image of a corner in the Newport side of the school ships St. Mary's and Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing. It is derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | So a crowd of grimy gamins got into the record books first with their reform school ship.

In the street language of today, they might say to those who currently omit them and their Mercury from New York maritime training history, "Get over it!"

'Get Over It!' Reaction Understandable, Unwarranted

Such a reaction from the Hart Island lads, while understandable, would be unwarranted.

Their reaction would be understandable because, having braved the perils of the deep, endured training ship rigid discipline, survived its squalid conditions, and, despite all, acquired mariner skills, many saw their hopes for sea careers dashed as so often potential employers rejected them out of hand. These youths' nautical skills having been learned aboard a reform school ship sufficed to disqualify them in the eyes of too many in the maritime industry.

Nevertheless, the theorized Mercury boy crews' reaction would be unwarranted. Whereas maritime employment rejections in their time may have reflected an open hostility, a publicly-stated stance of opposition, the current non-recognition more likely results from the limitations of institutional memory.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Image of entrance/exit door as seen from "lighthouse overlook," derived from one of a series of digital photos taken by the NYCHS webmaster during a July 17, 2009, visit to the museum. Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | The city school board's New York Nautical School and its successor, the New York State Nautical School, were so desirous of disassociating in the public's mind their training vessels from the reform school ship, that they also wiped it out of their own minds, institutionally speaking.

After decades of not mentioning the Mercury directly, and only occasionally by indirect inferences such as noting their own boys came from "good families," the reform school ship ceased to exist as a memory to go unmentioned.

The memory avoided eventually became the memory voided.

Thus the current non-acknowledgment of the reformatory ship boys' accomplishment lacks the intent that might warrant being answered with the snappy "Get over it!" rejoiner.

Rather the boys aboard the ghostly Reform School Ship Past should take heart -- and hope -- from the professional excellence of the SUNY Maritime College and its Maritime Industry Museum. Their professional adherence to standards of academic integrity provides grounds for believing that

gracious and generous-hearted recognition will be forthcoming in due course, and in some material form, now that their attention has been called to the matter.

|

XXX

XXX |

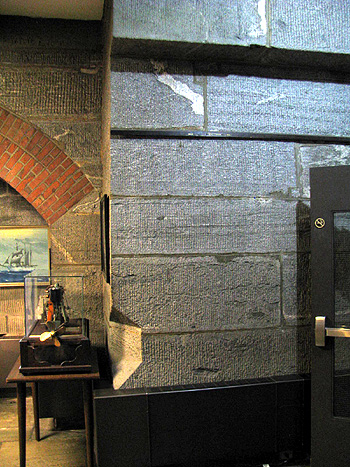

|

Above is that previously mentioned blank wall near the St. Mary's & Newport section of the Joe Gerson Training Ship Wing. Wouldn't it be a great spot to place a framed illustration of the Mercury with a caption noting the NY Public Charities & Correction's nautical training ship operated from Hart Island 1869-76? Click image to access Maritime Industry Museum at Fort Schuyler's own description of touring it. | | Hoist her colors high, hardies. The fog of institutional forgetfulness is lifting.

Hove to, boys. Bring her in closer for viewing by them upon the 21st Century shore.

Let them see your 19th Century packet full sail, New York's own first maritime training ship.

Show them the swiftness of your namesake Mercury, god of commerce.

Your voyage back from oblivion is ending.

But you'll have little time to rest.

Soon you will begin to cruise the waters of historical rediscovery.

So look lively now, lads. Look smart, swabs.

At long last, you have won attention.

Make it count.

|