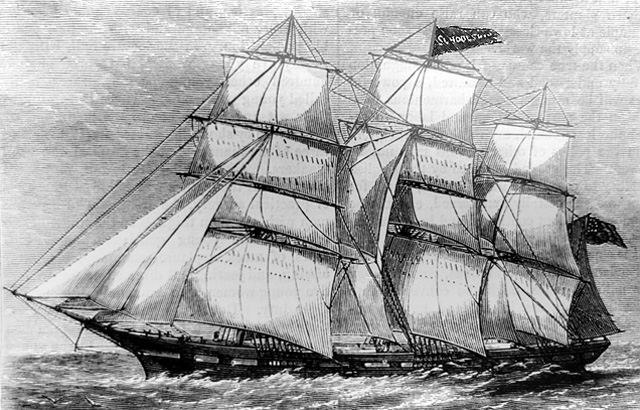

| School Ship's Best Day in Not Very Good Year

Perhaps the Mercury's best day in 1874 came April 22 when Sir Lambton Lorraine was being feted by NYC's mayor, Common Council members, state legislators, sundry Commissioners and other office holders.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

The modesty exhibited by Sir Lambton Lorraine (above), faced with NYers' adulation for his role in the Virginius Affair, has enhanced his stature with time, given later corrections to earlier versions of the incident.

His rapid response in that emergency may well have helped saved lives. The summary executions of non-Cubans that had taken place seem clearly to have been carried out with little or no regard for the legal processes called for under international law. Nevertheless, subsequent investigations appear to have established that indeed the steamer was not entitled to fly the American flag, that it was rebel-owned and that it was on one of its frequent missions to aid the rebel cause when captured. While many Americans were sympathetic to the Cuban revolutionary cause, the official U.S. stance was non-involvement.

For a more detailed recounting of the the Virginius Affair, click the image above. Use your browser's "return" button to return here.

Below: image of "Spanish man-of-war Tornado chasing the American steamer Virginius."

Source: John Gilmary Shea, The Story of a Great Nation (New York: Gay Brothers & Company, 1886) Retrieved

from

http://etc.usf.edu/clipart/5600/5681/

virginius_chased_1.htm Clipart ETC is a part of the Educational Technology Clearinghouse.

To access that, click the image below. Use your browser's "back" button to return here.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

| He had commanded the British war steamer Niobe, whose arrival in Santiago de Cuba waters after the capture of the American steamer Virginius on the high seas by the Spanish Cuban steamer Tornado on November 3, 1873 was widely credited with helping to save the lives of about 120 of the ship's 170 passengers and crew members. They had survived the summary executions carried out during the seizure and immediately afterward but were being held prisoners.

The British gunboat's weaponry pointed at Santiago was viewed as having backed up the diplomatic efforts taking place to untangle an international mess caused by some over-zealous Spanish Cuban officers at a time of rebellion by certain native nationalist factions.

While Sir Lambton kept insisting whatever happenstance contrived to place his gunboat in those Cuban waters at that time, he was glad the effect proved helpful, but that his role had been only a small one.

Nevertheless, city leaders insisted on treating him as a hero, in part to show appreciation, but also to demonstrate outrage that a merchant ship out of NY, one flying the American flag, could be seized on the high seas and some 50 of those aboard executed summarily.

What better way to salute a naval hero, the city fathers reasoned, than to take him by the Public Charities and Correction (PC&C) steamboat Minnahanonck on a tour of the municipality's island institutions, especially Hart Island's nautical school ship for training street youths to become mariners.

The sailing vessel had returned only 10 days earlier from its annual spring cruise in the West Indies. With 217 boys aboard, the ship had touched at Barbadoes, Martinique, and St. Thomas and been visited by the commander and officers of the British West Indies squadron. The voyage had gone well with no deaths or casualties, the NYT of April 13 reported.

More officialdom, more VIPs, more movers and shakers, seemed to have descended upon the Mercury the morning of April 22 than had come aboard during all five years of the school ship's operation up to then.

Of course, most came more to see and be seen with the hero of the day, Lorraine, than to see the nautical training vessel itself. The NYT of April 23 reported

|

. . . on the Minnahanonck [Sir Lambton] had some peace until he put his foot on board the Mercury. Here all the shivering little embryo sailors were paraded to meet him, and had to jump up the rigging like monkeys, to loose sail, to man the rigging, to clew up the sails again, and then to get down on deck once more, and then give three lusty cheers at the bidding of their officers. . . .

Sir Lambton . . . told the boys to stick to their work, not be afraid of hard weather, to shout "Hail Columbia" and "The Star-Spangled Banner," and that he had no doubt they would become first-rate sailors in time.

|

He Should Have Doubted Mercury Boys' Sea Future

But Sir Lambton should have had doubts about that. Certainly the officals escorting him had their doubts about that, notwithstanding their nodding heads and grinning smiles of approval at his remarks,

|

XXX

XXX |

|

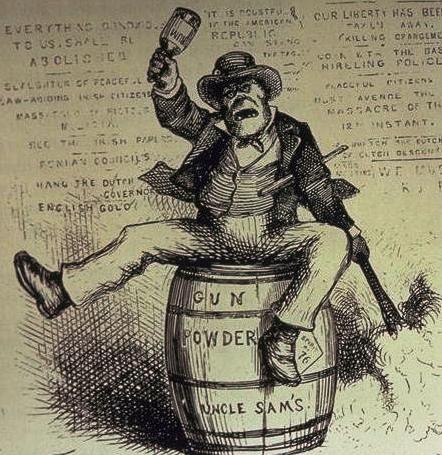

Michael Allen Gordon, in his The Orange Riots (Cornell University Press, 1993), details the perception that some Democrats and Irish (not necessarily all Tweed Irish Democrats) held of Mayor Hayemeyer's administration, and of the movement behind its and Gov. Dix's administration coming to power: a resurgence of anti-Catholic, anti-Irish, anti-immigrant Know-Nothingism.

Whether such nativism was a factor or not, few obviously Irish names appeared among their appointees. Those sharing this perception may have seen its confirmation in the NYT post-election editoral (11/7/1872) entitled "Some Useful Lessons:"

the rule of one class, and that the most ignorant class in the community, is over. The ignorant, unthinking, bigoted hordes which Tammany brought up to its support year after year are hopelessly scattered. Americans -- truly so-called -- are determined. . . . . This is going to be

an American City once more -- not simply a larger kind of Doublin.

For Google Books access to The Orange Riots, click the image. Use your browser's "back" button to return here.

|

| For even as the Brit's words of encouragement floated away on the springtime breezes blowing across the waters of Long Island Sound, long-gathering winds of change in the halls of government and in the counting houses were about burst forth.

Among other effects elsewhere, they would wreak political and financial havoc on the Hart Island reformatory school ship program.

The adverse impact of the Panic of 1873 on NY's commerce translated into reduced revenues in 1874 to fund municipal government.

Given the decrease in municipal income, the Board of Apportionment told the Charities and Correction Commissioners -- then three in number: - Democrat Myer Stern, and

-

Republicans James Bowen and William Laimbeer

-- that their projected expenditures had to be cut by $218,000.

The appointment of Laimbeer and Stern, both associated with Reform movement, and the reappointment Bowen, a PC&C board member since 1865, to the PC&C board on May 9th, 1873 [NYT 5/10/1873]by Mayor William F. Havemeyer, a reform Democrat elected on the fusion Reform/Republican ticket, put together a volatile mixture that boiled and bubbled 21 months until it burst. Arguably the ignition came from former State Senator Laimbeer who seemed prone to spark controversy. . . . and to be drawn to it.

Only some six months after reading about William Laimbeer's PC&C appointment, NYers read about the "Hon. Wm. Laimbeer" playing a leading role in a Cooper Union rally called ostensibly to organize against the preceived threat to "our common schools" by the growth of faith-connected educational institutions, particularly parochial schools.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Son of a minister, Dexter Arnold Hawkins (above) was an educator, lawyer, and political reformer whose ability and energy to research an issue, publicize the claimed findings, frame a legislative response, organize a campaign in support, and lobby its passage made him a major intellectual force on the NY scene in the 19th Century. His was a significant role in NY's adopting a compulsory education law and various prohibitions against state/city aid to parochial schools and other sectarian educational institutions.

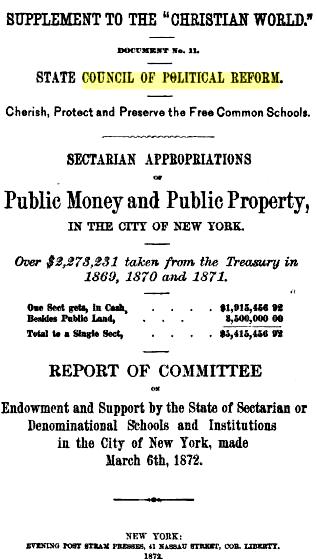

His rhetoric sometimes seemed to stray from arguing the public policy question at hand and to edge toward attacks on the Pope, the Catholic Church and Catholicsm in general. In his influential March 1872 Council of Political Reform document "Sectarian Appropriations of Public Money and Public Property in the City of New York," Hawkins declared:

|

a single sect . . . taught by its head, a foreign and despotic ecclesiastical prince . . . . makes war upon our public schools; persuades its children to leave them; sets up an opposition school, wherever it has a church, and admits that it does this solely for the purpose of indoctrinating the young mind with its peculiar sectarian tenets and observances. . . .

|

Hawkins' arranged to have the lengthy document printed the following month as a special "Supplement to the 'Christian World'," a publication (1850-1884) largely devoted to critiquing most, if not all things Catholic, as a way of converting Catholics to evangelical Protestantism.

What makes Hawkins' placement of his essay in the magazine particularly interesting is that in March, the same month he issued the report, the publication used what was entitled a "correction" of an article as an occasion to ask and answer the question: "Who Are Our Criminals?"

|

How comes it that certainly between three-quarters and four-fifths, and probably a still larger proportion of our criminals, are from the nominal adherents of the Roman Catholic church ?

. . . after making all due allowance for the comparative poverty of many of our Roman Catholics that come to us from abroad, does not this fact demonstrate that the church, here or elsewhere, which has fostered the ignorance and tolerated the low standard of morality from which this harvest of criminals has sprung, is unfit to effect a reformation in the character of those who are imprisoned as being, or soon likely to be, the bane of society ?

Indeed the question might well be raised, whether in view of this palpable failure of the Roman Catholic church to effect a radical reformation among its own members, the entire religious instruction in our criminal institutions ought not to be confided to Protestants, who can at least offer, historically speaking, a better prospect of imbuing those confided to their charge with sound principles of morality.

|

The "correction" onto which the magazine editor attached the above rhetorical question dealt with erroneous allegations in a January article about the Catholic chaplaincy aboard the Hart Island school ship Mercury. It was entitled "Jesuitism in our Public Institutions" and had been submitted by someone known to the editor but who wanted to be identified only as "Watchman."

However, separate letters by the Protestant chaplain, the Rev. Marinus Willett, and by the Catholic chaplain, Rev. Father Henry Duranquet, S.J., pointed out the article's factual errors which had been the premise of its charges and prompted the editor to acknowledge the inaccuracies, albeit with the graceless closing comment.

Chaplaincy aboard the nautical school ship may have brought back to Rev. Willett his own seafaring days before he decided to enter the ministry. He had been an officer on the Artic and the Ashburton. Fr. Duranquet participated in a piece of NY maritime history July 13, 1860 when he ministered as Tombs chaplain to the condemned pirate and triple murderer Albert W. Hicks whose execution on Bedloe's Island drew thousands of spectators watching from all sorts of watercraft that gathered around what one day would become home to the Statue of Liberty.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

| Any public monies going to them, even for stated secular purposes, were viewed as violating the First Amendment. In addition, the mere existence of these separatist schools was seen as running counter to the "melting pot" process by which immigrants became Americanized. Any increases in the number of these schools and in the number of students in them were seen as coming at the expense of the public school system.

Those views had then, as they have now, recognized standing in civic arena debates and discussions about the proper application of the non-establishment/ free exercise clause, and about the proper roles of -- and rules for -- schools in American society.

But, while some at the Oct. 27, 1873 rally spoke in lofty terms of Constitutional principles and democratic educational goals, what most seemed to move the audience that filled the hall to overflowing were the anti-Catholic harangues by the other speakers.

The NYT Oct. 28 account added bracketed inserts for audience reactions to speakers' remarks. Thus were recorded "[cheers]" of the audience for the Rev. Dr. King's identifying the "Romanish Church" as the source of "the tumult and opposition" to the common schools and for his challenging anyone to name a single Catholic bishop who had sworn allegiance to the U.S. Constitution. "[Cries of 'Never']" responded to the alledged quote he attributed to a boasting priest: "We rule New York and we will yet rule the country." "[Cries of 'Protestant']" responded to Dr. King's rhetorical question of where life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are best secured, Catholic or Protestant countries.

"[Applause]" repeatedly punctuated the speech recorded as made by the Rev. W. H. Boole of the 17th St. M.E. Church. Among other things, he said that for "more than 25 years the Catholic Church has been putting the thumbscrews to our politicians," promising to deliver them the votes if they will "blot out" the public schools.

Those emotion-laddened speeches had followed dryly-reasoned remarks by Council of Political Reform executive committee member Dexter A. Hawkins, its education chairman.

He called for NYC to try compulsory education and for the Church to stick to religious instruction and "not in any way interfere with the Government's secular education."

Hawkins' exposition had followed a resolution read by the Hon. Wm. Laimbeer. Adopted unanimously, it demanded, among other things, that any scholos not under public school authorites be excluded "from any share of public monies."

However, the event ran too long for him also to read an "elaborate paper on the public school question."

That document -- prepared by a rally committee and printed in full by the NYT Nov. 8 - argued that "licentiousness, crime and pauperism" in NYC was "nothing compared with the lust, murder, rapine, brigandage, and insecurity" in most countries where the "Romanish hierarchy holds unlimited sway" over education.

The committee's "elaborate paper" -- quite possibly Dexter A. Hawkins had hand in writing it as likely did the Hon. Wm. Laimbeer who had planned to read it -- referred to Pope IX as a "foreign potentate." Since for some years the Pope no longer had temporal rule over any territory anywhere, application of this term (loaded with negative connotations) was evidentially aimed at the Pontiff's spiritual role as church leader:

|

Our foes hold allegiance to a foreign potentate from whom has gone out a fiat to destroy our schools and subvert our educational laws. . . . . The time may come when unscrupulous politicians, to secure political influence of the Jesuitical power, may combine to deprive us of our schools . . . . Let it be distinctly understood the policy which our opponents propose to establish is a foreign one, emanates from a foreign potentate, and is prosecuted by foreign emissaries . . . .

|

Reform/GOP Commissioner Laimbeer: Ax the Ship

Attempting to comply with the Board of Apportionment's 1874 directive to reduce its projected budget, the PC&C commissioners found that cutting salaries resulted in savings of only $35,000.

Eliminating the mid-day steamer to Blackwell's Island saved $12,000. Doing without 20 of the 70 horses working at PC&C facilities in Manhattan and on its institutional islands was considered.

But Republican Laimbeer also urged eliminating the nautical training program entirely, according to the NYT of July 11:

|

Commissioner Laimbeer has made a proposition to abandon the school-ship Mercury, and send the boys to Randall's Island. He says the proportion of boys who have entered the navy or merchant service from the school-ship is very small indeed, and that the experiment of training boys as sailors has proved a complete failure. . . . . when they get an opportunity, they desert the vessel. . . the ship was costing a good deal, and he was for abandoning but his associates on the Board did not agree with him. . . .

|

Nativism in New York City: Harper & Cartoons

|

XXX

XXX |

|

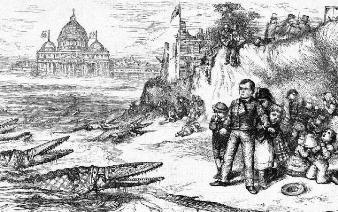

The anti-Catholic nativism that some critics claimed as seeing resurgent in the movement that brought Gov. Dix and Mayor Havemeyer's admistrations to power in 1872 had reared its head four decades earlier. In 1836 the publishing house of James Harper (image above) published as non-fiction the scurrilous and later discredited Maria Monk's Awful Disclosures.

Its fictions presented as facts helped spark, fuel and fan the fires of anti-Catholicism in America that found political expression in various nativist parties. Reportedly selling more than 300,000 copies, the book also helped establish the firm (Harpers & Brothers) as a major player in American publishing in which role, to its credit, it made significant literary contributions.

But, at the time, James Harper was able to ride the continuing wave of nativism as a candidate of the anti-immigrant American Republican party and won election as mayor in 1844. For a family member's view of James Harper's becoming and serving as mayor, click the image above. Use your browser's "back" button to return here.

Lending credibility to the perception of the movement behind Dix and Havemeyer in 1872 bearing some resemblance to the movement behind Harper in 1844 was the significant role played by Harpers' Weekly political cartoonist Thomas Nast in helping bring down the Tammany machine.

The virulent anti-Catholic and anti-Irish aspects of Nast's cartooning -- such as drawing Cardinals as crocodiles and Irish as drunken apes (see images below, click to access) -- are generally acknowledged even by those hailing his attacks on the Tweed Ring and slavery and his defense of Native Americans and Chinese Americans.

|

|

XXX

XXX

XXX

XXX

|

|

PC&C Commissioner Laimbeer's calling for sinking PC&C's nautical school program was just one development among several in 1874 that did not bode well for its continuance:

-- The Board of Education's Committee on the Nautical School -- headed by Commissioner David Wetmore, joined by Commissioners Matthewson, Seligman, Dowd and Vermilye -- began its work on Jan. 21, 1874, according to the NYT next story.

-- Although Commissioner Bowen (a member of PC&C board which launched the school ship program and credited by some as its initiator) was understandaby reluctant to shut down what he had sired, the PC&C in late April scheduled an inspection of the Mercury for May 12. Its purpose, in the words of a NYT April 30 item, was to "ascertain what progress has been made by the establishment of this public institution."

-- A one-paragraph NYT story of Oct. 3, 1874, labeled "The Board of Education," reported the finance committee issued a statement detailing appropriations requested for the coming year, including "$50,000 asked for the support of the nautical school to be established."

-- A one-paragraph no-headline item, tucked among more than two dozen educational items of local, regional and national interest under a general NYT heading "Educational Notes," Oct. 10, 1874, reported the NY Bd. of Ed. was seeking an appropriation of $3,683,000 for the coming year, including "$50,000 for the nautical school proposed to be established."

-- On Aug. 5, 1874, the special meeting of the Board of Education was held to nominate Navy Commander R. L. Pythian to the Secretary of the Navy for assignment to skipper board's school ship. The action was taken in anticipation of the Navy Secretary acting favorably on its request for a vessel being made available to serve as the board's nautical training ship, according to the next day NYT story.

-- The nautical school committee of the Board of Education reported favorably on selecting Dr. Daniel C. Burleigh as surgeon and instructor for it, according to the NYT of Nov. 19, 1874. He had served in the Civil War as an assistant surgeon aboard the Unadilla and later the Tioga, according to the United States Service Magazine of 1865.

A Dec. 17, 1874, NYT story, mostly about the then new Compulsory Education Law, included passing mention that the school ship committee formally announced for the record that St. Mary's had arrived and was moored at 23rd St. East River pier.

As St. Mary's Arrived, Mercury Readied to Ship Out

But its scheduled arrival Dec. 9 had already received its own headlined NYT story:

|

THE NAUTICAL TRAINING-SHIP.

The United States Sloop St. Mary's

Expected in New York Harbor Today

A Chance for Public School Boys

To Learn A Profession.

|

The sloop-of-war had left the Boston Navy Yard Dec. 7 under tow of the U.S. steamer Gettysburg. The story, that in its praise of the planned training read more like an editorial endorsement, declared:

|

The course of instruction . . . will extend from 18 months to two years, according to the aptitude they may individually display; the but successful boy will be allowed to continue his studies . . . until he has fitted himself to fill any rank . . . in the marine profession to which he may aspire.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

|

GOP leader Thurlow Weed (above), who had a hand in close friend James Bowen becoming PC&C Commissioner, may have had a hand in keeping Bowen's school ship afloat at least until 1875 year end. Bowen is mentioned a dozen times in

the Life of Thurlow Weed including his autobiography and a memoir by Thurlow Weed, Harriet A. Weed, Thurlow Weed Barnes.

For Google Books access, click the image. Use your browser's "back" button to return.

|

|

The PC&C Commissioners on Aug. 8, 1874 ordered the Hart Island warden to "prepared the stones for a building 40 by 300 feet, for the accomdation of the boys now on the school ship Mercury, according to the next day NYT one-paragraph item in a round-up column of news bits.

The end-of-year budget process in 1874 saw some effort to stave off the move to eliminate funding for the Hart Island nautical school.

During the Nov. 12th proceedings by the Board of Aldermen on projected expenditures for 1875, Republican John J. Morris, who was a protege of Thurlow Weed, PC&C Commissioner Bowen's close friend and GOP power figure, moved to strike from the PC&C appropriation the words

|

"The above contains no provision for the Free Labor Bureau after May 1, 1875; the school ship Mercury and the steamer Bellevue after Jan. 1, 1875."

|

Thurlow Weed's Christmas Present to Bowen?

The matter was referred to committee, where presumably it could have been bottled up but wasn't. The NYT story Christmas Eve on the Board of Apportionment's final budget actions the previous evening, reported a development that, from the PC&C Commissioner Bowen's perspective, may have seemed somewhat like a holiday season gift.

|

The recommendation of the Board of Alderman that the Department of Charities may continue to use the school-ship Mercury was adopted.

|

The NYT Christmas Day story expressed the same point with different wording:

|

. . . the clause preventing the Commissioners of Charities from maintaining the school ship Mercury and the Free Labor Bureau [was] stricken out.

|

With word that refitting of the Navy vessel St. Mary's for use as a school ship was preogressing rapidly, the Board of Education nautical training committee issued in late November its proposed rules and regulations for propospective students.

They were required to be volunteers but have their parents or guardians' permission, be 15 years or older, be physically up to nautical training regime, some capacity to read, write, and do the multiplication table, and "evince an aptitude or inclination for a sea life." These requirements were formally adopted by the board Dec. 2.

The NYT editorial writer used the installation of a new board of PC&C Commissioners as an occasion to call for more efficient "pauper and criminal managagement." A Dec. 28, 1874 editorial urged reducing expenditures in various of the agency's programs:

|

We have serious doubts also, whether the School-ship Mercury is a desirable branch, now that the Board of Education as a School-ship, to be supported at public expense.

The expense might be better employed in making Hart's Island School a real "industrial school," which should teach trades and help pay the cost of the institution.

|

As if to underscore the editorialist's opinion of the Mercury program, seven boys reportedly escaped from the ship the following day

|

XXX

XXX |

|

The St. Mary's that became the C. of C./Bd. of Ed. nautical school ship was named for a county in Maryland.

Above theSt. Mary's rides at anchor in the late 1800s. To fit her for her role as a training ship, her battery had been removed; her gunports providing light and air for berthing spaces below decks. Below are excerpts from her Naval Historical Center website "bio:"

(displacement 958 tons; length 149' 3"; beam 37' 4"; draft 18'; complement 195; armament 16 32-pdrs., 6 8" guns)

The 2nd St. Mary's, a sloop of war built in 1843-44 at the Navy Yard, Washington, D.C., was commissioned in the fall of '44.

Designated initially for duty with the Mediterranean Squadron, St. Mary's was at Philadelphia awaiting the sailing of her squadron, under Commodore Robert Stockton, when tension over Mexican-Texan-American territorial disputes heightened during the winter of 1845. . . . By the end of the month [March], Stockton's Squadron was ordered south to reinforce that of Commodore David Conner in the Gulf of Mexico. . . .

On 19 May, St. Mary's anchored . . . near Tampico. On the 20th, she proclaimed the blockade of that port and of the Mexican coast. . . . On 14 Nov., she participated in the unopposed occupation of Tampico; then resumed blockade duties. In late Dec., she was ordered to Brazos Santiago, whence, in Jan. 1847, she proceeded to Lobos to cover the movement of General Scott's troops. In early March, she escorted the transports into the Anton Lizardo anchorage. On the 8th, she moved toward Vera Cruz; and, on the 9th, her boats carried assault troops to Collado Beach, where Scott's force was landed, without resistance, in under five hours.

St. Mary's remained in the area through the end of the month to support the siege of the city. . . . On the 29th, the city was formally surrendered. . . On 10 April [1847], she had been ordered back to the U.S. . . . . in early May, she sailed for Norfolk, carrying captured Mexican guns as cargo. . . . .

On 11 April 1848, she sailed for duty with the Pacific Squadron; and, for the next five years, she cruised from the coast of Calif. to the coast of Chile, in the Central Pacific, and in the Far East. In 1853, she returned to the east coast of the U.S.; underwent repairs at Philadelphia . . . . During the next two years [1854-55], she cruised in the eastern and south Pacific; and, in Dec. 1856, she put into Panama City where a new crew under Comdr. Charles Davis relieved that of Cmdr. Theodorus Bailey.

From New Granada (Panama), Davis took St. Mary's to the Jarvis and New Nantucket Islands, then returned to Central America to stand by, off Nicaragua, as William Walker fought to keep his empire there. . . . . In early May, Walker surrendered to Davis. Walker and the other Americans in his army were taken on board St. Mary's and transported to Panama City, whence they were returned to the U.S. . . .

In March 1858, she put into Mare Island, Calif., for a refit. . . . . In late August, she headed south to cruise off Central America; and, in Feb. 1859, her officers and crew were relieved at Panama City. She then sailed north to cruise along the Mexican coast as revolution spread in Mexico. In the fall of 1860, she returned to Panama City. There, with HMS Clio, she assisted local officials in quelling an insurrection.

A few months later, civil war divided the U.S. Through [the Civil War], St. Mary's remained with the Pacific Squadron, protecting Union merchant shipping and searching for Confederate raiders. After the war, she cruised the Pacific until Sept. of 1866, then put into Mare Island where she was laid up for four years. In the fall of 1870, she returned to active service; and, after a cruise to Australia and New Zealand, she returned to Mare Island, whence in Nov. 1872 she departed for Norfolk.

On 3 June 1873, St. Mary's returned to Norfolk . . . . [later] transferred to the Public Marine School at NY, she served as a schoolship until 1908. In June of that year, she was ordered sold. Two months later, she was purchased by Thomas Butler and Co., Boston; and, in Nov., she was scrapped.

For ship's full bio, click the image. Use your browser's "back" button to return.

|

|

1874:

Not Good Year for Mercury;

1875:

A Disaster

If 1874 was not a good year for the Hart Island school ship, then 1875 must be counted a disaster. But it began well enough. Grand Jurors told the NYT after a Jan. 16 "minute but entirely informal inspection" that they were entirely gratified "at the discipline of the boys and the general cleanliness of each apartment."

A week later the Mercury departed Hart Island for its annual cruise to the West Indies.

On Feb. 2 a lad from the workhouse, taken on the cruise despite his sickly look, appeared so ill that he was ordered confined to the sick ward. His name: John Reilly. The diagnosis: typhus.

Seven other boys soon developed similar symptoms and were likewise confined away from the rest aboard. The seven recovered but Reilly died Feb. 12. Reportedly, except possibly for the owner of a liquor store at Ave. A. and 8th St., the youth was not known to have any adults taking an interest him outside of PC&C staffers. Efforts to contact the liquor store owner were made.

After reporting on the typhus Mercury outbreak in the straight news fashion, the NYT March 14th story suddenly lashed out with editorial opinion against the ship surgeon Dr. Piercy for having admitted the ill boy to the ship in the first place, thereby placing "the lives of every soul on board in jeopardy."

F. F. Gregory, who had been Captain Giraud's executive officer and who succeeded him as its skipper, made no mention of the Reilly death or typhus outbreak in his 1875 annual report submission.

Ship Teacher Johnson's Scathing Submission

Perhaps Gregory left the information out because the school ship's teacher, John C. Johnson, covered that in his scathing submission:

|

. . . . Sickness on our voyage, prevented our session of school, from the 4th to the 16th February, inclusive. The school room was used as an hospital. One boy, John Reily, died in our arms, and was buried at sea. . . .

A word, now, in regard to our quarters. When the weather is cloudy and foggy, it is so dark down here as to preclude the possibility of teaching satisfactorily without lamps, and at the present writing, in the middle of the afternoon, I can trace the lines only by aid of my candle.

There is, however, no provision made in this respect for the boys. To prepare recitations in the dark is severe on the eye. The provisions and facilities for ventilation are still worse. The air streak that carries up from the lower portions of the ship the noxious gases of the bilge-water, and besides, the heated exhalations of the sail-room, and of the boys. underclothing, opens into the school-room.

And to aggravate matters still worse, the ship is infested with rats and mice, and it is known that rats when they become very numerous kill one another. Their stench is simply repulsive.

When the boys have assembled for a while in a questionable state of personal cleanliness, in the hot months of July and August, during which we are obliged to teach, the atmosphere becomes so fetid, that we experience a sensation of faintness come over us.

Upon one occasion, while cruising under the tropics in the gulf of Paria, we led the boys from the school, fainting and sick, till sixteen (16) were strung abaft the armory. Before we had time to leave the gulf, one boy, Hugh McKinnan, died, and was buried at San Fernando, Trinadad.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

|

One of the official visitors inspecting the Mercury in late 1875 was Theodore Roosevelt Senior (above), whose son TR Jr. became Assemblyman, Police Commissioner, Secretary of the Navy, Governor, Vice President and President, and whose granddaughter Eleanor Roosevelt became First Lady as Mrs. FDR.

Family wealth derived from its successful imported plate glass business enabled TR Sr. to devote considerable time to civic, cultural and charitable endeavors. He helped initiate, organize or lead the following, among others:

-

American Museum of Natural History

- Metropolitan Museum of Art,

- New York Children's Orthopaedic Hospital,

- Children's Aid Society,

- Union League,

- State Board of Charities,

- Newspaper Boys' Lodging House,

- Protective [Civil] War-Claims Association,

- Soldiers Employment Bureau,

- Soldiers' Allotment Commission,

- State Charities Aid Associaetion and

- Sanitary Commission

For more bio info, click the image. Use your browser's "back" button to return.

|

| Whereas Johnson noted by name the deaths of two of his students, two others who also died in 1875 went unnamed.

Among the 422 boys aboard the ship at one time or another during the year, four died according to one of the statistical tables accompanying the annual report submissions by Gregory and Johnson.

From another table's entry, the indication was that those two unnamed deaths occurred in November.

The last of the more than half dozen 1875 cruises by the school ship was completed Oct. 16, so those two deaths occurred while the Mercury remained at her mooring.

While the ship was still on its 1875 annual "long voyage," the death of its former skipper took place back in Manhattan.

Pierre Giraud had skippered the vessel more than three years including its "finest hour" -- the scientific research cruise to Africa.

He died at 4 p.m. on the 4th day of 4th month at his home. He was only 42.

While the PC&C Commissioners had managed to save the school ship from budgetary ax wielders in 1874, the continuing depression of NY's economy in wake of the 1873 Panic made even more and deeper cut necessary in 1875. The school ship had to go.

As if to hammer the last nail into the coffin even as the terminal patient still lingered this side of death's door, a committee of distinguished citizens and naval officers who had inspected the Mercury issued a report Dec. 21, 1875.

The Last Nail Hammered Into Ship's Coffin

That inspection report resulted these NYT story headlines the next day:

|

THE MERCURY IN BAD CONDITION

Unfavorable Report Regarding the School-Ship

-- The Result of the Examination by

A Board of Visitors

|

Actually, a reading of the story itself reveals that the report was somewhat more balanced than the headlines seemed to suggest.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above is a late 19th Century image of the main building of the girls department of the Catholic Protectory in what was Westchester when built but is now Parkchester, the Bronx. It was headed for 16 years until his death in 1890 by Henry Louis Hoguet, banker and leader in benevolent causes.

Hoguet's 1875 inspection of Mercury came, as did TR Senior's, as a State Charities Board member.

A reading of the Protectory's founding in the early 1860s makes clear its originators felt compelled to establish a house of refuge for homeless or wayard children of their faith because existing institutions -- predominantly Protestant in the orientation of their administrations, staffing, reading materials, instructions and Sunday services -- were perceived as proselytizing in effect, and sometimes even by intent.

For more about the Protectory's early history (particularly pages 7 and 17-21) and Hoguet's role in it (particularly pages 49-51), click the image which is from The Catholic Protectory of New York: Its Spirit and its Workings from Its Origin to the Present in the "History of Child Saving in the United States" by the Committee on the History of Child-Saving Work, National Conference on Social Welfare, 1893. Use your browser's "back" button to return.

|

| The Board of Visitors included State Board of Charities Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, father of the future Governor and President; Roosevelt's fellow Commissioner, Henry L. Hoguet, president of the New York Catholic Protectory for children; Naval officers Stephen B. Luce, Richard W. Meade, and Henry Bellows Robeson, all future admirals.

They reported themselves favorably impressed with the adaption of the former packet for its educational purposes, its overall neatness and general cleanliness, and the apparent good health and alertness of the lads.

However, they found the crew cabins discreditable, the boys' clothing thin, their bedding scanty and dirty, and their knowledge of matters nautical inadequate.

Recommendations to the PC&C Commissioners included limiting student in-take to those whose commitments under law allowed long enough periods for the nautical education and other training to gain effect. Mercury Captains Giraud and Gregory had made much the same suggestion in their submissions to the Commissioners' annual reports.

Giraud wrote in his submission for the Commissioners' 1870 annual report:

|

The majority of the boys comes to us for no stated period, and consequently only concentrate their thoughts from day to day on the probable time of their discharge. Under this constant chafing their thoughts are far from duty or study, and the ship becomes a prison for them.

. . . if the boys were made to feel that their stay was to be at least one year, or until they had made certain progress in seamanship . . . determined by examination, they would . . . apply themselves.

|

Gregory wrote in his submission for the Commissioners' 1875 annual report:

|

The constant changing of classes resulting from the daily reception and discharge of boys proved . . . a detriment to the school. This may be avoided by fixing a term for every boy admitted to this ship . . . . Cases without number haved occurred, whe a boy, after a service of three months, has been taken away by his parents, only to return to the old . . . associtionss which caused his commitment to this institution

|

|

XXX

XXX |

|

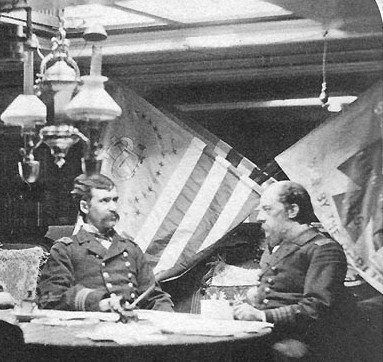

Above is an 1877 image of Captain Stephen B. Luce, USN (at right), Commanding Officer of the USS Hartford, seated with another officer (name unknown) in the captain's cabin aboard that steam sloop at Hampton Roads, Virginia. He was the Hartford's captain at the time of his late 1875 inspection of the Mercury.

One wonders how Luce, for whom the SUNY Maritime College's library is named in honor of his contributions to naval and maritime training, would account for the current historical disregard of that first NY nautical school ship -- the one he examined in its 6th and final year of training service.

Click image to access more about Luce from the Naval Historical Center. Use your browser's "back" button to return.

|

| The NYT report of Dec. 21, 1875, said the Visitors Board stressed that, even among those youths whose committments to PC&C care and custody were sufficiently long enough, "only those who evince a taste and aptitude for a seafaring life should be selected."

Unfortunately, from Mercury's perspective, the December 21, 1875 recommendations came too late.

Opportunity to fix defects in the reformatory school ship program had long passed.

Perhaps more damaging than the NYT headlines was a table from the Board of Visitors' report inserted into the story.

It showed the average daily number of students participating in each of the six full years of the nautical training program, the annual cost, and how much expense that meant per student per day.

The point behind the agency working up the table for the visitors was to show how the daily cost per boy had been about 60 cents in the beginning but was reduced to 40 cent six years later.

Tables Tell Tale: Too Much for Too Few

But more likely to strike the taxpayers reading the table was annual cost figures: from close to $60,000 to start but still nearly $30,000 six years later with the total tab for those six years approaching $300,000.

For that outlay, the numbers of Mercury graduates entering the Navy or maritime service seemed rediculously few.

In his submission for the Commissioners' 1875 annual report, Captain Gregory remarked that

|

The class of boys received during the past year has been better than in any former year; not more than seven really incorrigibles having been received. The number of orphans at date is 37, the number having been much reduced by the shipment of 20 or more in the naval service.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above is an image of the 1875 PC&C annual report statistical table described in this web page's main text to the left.

Below is an image of the 1875 PC&C annual report statistical table described in this web page's main text beginning seven paragraphs above (starting with the words "Perhaps more damaging").

Click either image to access Captain Gregory's 1875 report. Use your browser's "back" button to return.

|

|

XXX

XXX |

| One of the statistical tables accompanying Capt. Gregory's submission showed 24 "shipped in the U.S. Navy" and 4 "shipped in merchant [marine] service." If one counts the 28 going into naval or maritime service in relation to the 422 boys aboard the ship at one time or another during 1875, the percentage works out to about 7 percent.

If one counts the 28 in relation to the 233 average daily numbers of boys aboard, the percentage of school ship lads entering upon a seafaring life runs about 12 percent. Either way, the 28 divided into the $28,538 cost that year could have looked like more than $1,000 spent on each.

Too much for too few.

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above: sketch of William H. Wickham, Apollo Hall anti-Tweed Democrat who was NYC mayor in Mercury's final year.

He had a hand in municipal budget cutting that shut Hart Island's nautical school. Earlier in life, he had worked for Pacific Mail Steamship Co. Click image for more. Return via "back" button.

|

| Formal announcement of the steps scheduled to shut down the Hart Island-based nautical training program came the morning of New Year's Eve, Dec. 31, 1875. Citing the action of the Board of Apportionment cutting PC&C's 1876 budget appropriation from the $1,366,993 requested, to $1,163,000, the agency's Commissioners said they were forced to discontinue what they considered "one of its most important and needful institutions:" the school ship Mercuty.

The NYT Jan. 1, 1876 story said the ship would be "laid up in ordinary," the services of the 21 officers, adult crew members and staffers terminated, and the boys under 16 distributed to charitable institutions in the city and vicinity, and those 16 and older retained on Hart Island under its warden.

In their 1875 annual report, the Commissioners succinctly noted that the School Ship Mercury and the agency's Free Labor Bureau (to help the unemployed find jobs) had to be "discontinued because of want of funds for their maintenance."

Since Mayor William H. Wickham, to whom the annual report was officially submitted, had been very much involved in the budget cutting process against the backdrop of a continuing economic depression, he needed no lengthy explanation.

Whereas the PC&C annual report that first mentioned the Mercury had been submmitted to the state Legislature -- in January of 1870 to cover the year 1869 --

|

XXX

XXX |

|

Above is the cover of the 1875 PC&C annual report, the seventh and final one to include information on the "Mercury." Click to access. Use browser's "back" button to return.

|

| the annual report for 1875, the last to mention the nautical school ship, was sent to the mayor in January 1876 to conform with the May 1870 reorganization of NYC government.

Whereas the Commissioners signing off on the Mercury debut year annual report were evenly balanced politically in terms of party affiliation (2 Democrats, 2 Republicans), the party affiliation line-up for the annual report last mentioning the Mercury wasn't so balanced.

It consisted of two Democrats (Young Democracy/anti-Tammany Townsend Cox and Tammany veteran/former Bellevue Warden Thomas S. Brennan) and one Republican (Isaac H. Bailey, PC&C president).

None of the three had been on the PC&C board that launched the nautical school program a half dozen years earlier.

|