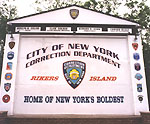

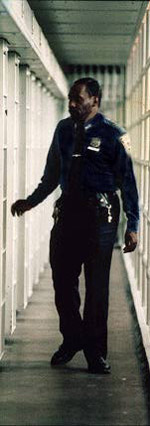

A view of Rikers Island. [All images on this page are from elsewhere on this web side, except the two below from the book's covers.] |

|

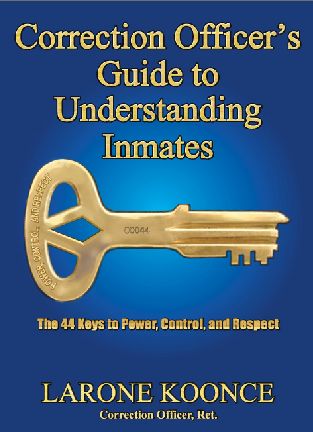

Correction Officer's Guide to Understanding Inmates

From the Introduction: I, like most of you, did not have a relative or family

friend in the department that pulled strings for me. I didn't

have a hook. I couldn't make a phone call to get a steady

post or to get a supervisor off my back. But throughout my

career I was lucky enough to come across senior officers

who took an interest in me and taught me what I needed to

know to make the job work for me.

Now, I want to pass on what I have learned to you. Why

take a career’s worth of experience and put it on the shelf

when I can share it with you? You shouldn't have to learn

things the hard way, the way I and many other officers did.

You shouldn't have to reinvent the wheel. . . .

Only the names have been changed . . .

I have written this book to help officers who are trying to work their way the maze of that is the Department of Correction. I want to help those officers make it to retirement without being mentally or physically injured like so many of my friends and colleagues. I have seen officers lose their marriages, their families, their health, their jobs, and their lives during my years in corrections, and I want to prevent as many officers as I can from going down that path. . . .

This is an honest book with real accounts of actual events that have occurred during the course of my career.

The names have been changed to protect the identities of those involved in the events and incidents.

I have chosen to use the masculine default to streamline the prose. This choice is not meant to overlook the many brave and courageous women who serve as corrections

officers or to imply that only men are inmates. . . .

From the third chapter: The chiefs took great care not to let the rest of the facility

know that the warden was in error. The chiefs would never

reprimand a warden in front of his command.

You wouldn't like it if the captain reprimanded you

about your uniform in front of your peers at roll call.

You would prefer that he pulled you to the side before or

after roll call and spoke to you about it. It’s more professional.

When you need to instruct or reprimand an inmate,

walk up to him, and do it in a manner that will not be so

noticeable to all the other inmates. You will get better

results. If it is not an emergency and can be done at another

time, when the other inmates are not around, wait for that

time to tell the inmate of his mistake....

I often would have conditions attached to honoring

inmates’ requests. For example, if I noticed earlier in the

tour that an inmate had been too loud and boisterous during

breakfast, I would remind him of his unacceptable behavior

when he asked me for something. I would tell him that I

would honor his request but during lunch, he would have to

tone it down. . . .

From the ninth chapter: We would

respond in waves of twenty or more all suited up with riot

vests, helmets, and batons led by a deputy warden.

We ’d stand at the door of the housing area in full view

of the protesting inmates in formation twenty and sometimes forty officers deep, all champing at the bit and itching

to rush in to do battle with them.

Then the deputy warden

would go into the housing area and negotiate with the leaders of the protest while we stood in the corridor.

We would stand there waiting for the signal to attack.

After about fifteen or twenty minutes the deputy warden

would emerge from his conference with the inmate leaders

and tell us that everything was settled, and the inmates

would take down the barricades. While we stood in the corridor, the deputy warden always gave us a speech about why

he negotiated with the inmates.

The Koonce book has no images illustrating the text. For design and informational purposes, relevant images have been added on this page and captioned by the webmaster. Most of us that were suited up in riot gear felt that what

the deputy warden was saying was a copout and maybe he

was scared of going to battle with the inmates, but we

weren't. We wanted to break through those barricades and

teach those inmates a lesson.

As I got older and wiser I realized that the deputy warden

was absolutely right. My fellow officers and I, who wanted

to go to battle, were wrong. The deputy warden wasn't

coping out; he was acting responsibly. He knew that it was

better to use whatever legal and ethical tools at his disposal

to get the outcome that he wanted without using force.

When you use force, you risk getting people on both sides

hurt.

I've been on riot squads that were allowed to take back

housing areas by force and almost every time officers and

inmates were injured. I have concluded that it is always

better if cooler heads prevail. Take a long-term view of your

career in corrections; if you expect to have a long career and

make it to retirement, you have to be smart. Don’t use force

if you can find another way to get the desired results.

Most inmates are not troublemakers and want to comply

with the rules, but they also want to be respected. They

don’t want to lose face or be punked in front of the other

inmates. If you give them a way out of a sticky situation

that doesn't include violence, they will usually take it.

However, if you back them into a corner with no other

options, they will fight no matter what the odds are. The

smallest mouse, if backed into a corner with all avenues of

escape cut off, will fight you to the death. However, if you

leave him an avenue of escape no matter how small the

avenue, he will chose to escape rather than fight. You don’t

have to always go to blows with the inmates to get them to

do what you want. . . .

Family

From the twelfth chapter: We

often had to work double shifts (sixteen hours) on our first,

second, and fourth days and on our third day we would have

to work at least two and a half hours overtime for some officer who took time due. (If you are a new correction officer, you will learn about time due when you get to your facility,

if not before.)

Occasionally, even on our third day we would

have to work sixteen hours. It was especially tough on me

because I didn't have a car for the first year, so I had to take two trains and a bus from Brooklyn to Rikers Island and back.

Although conditions are better now for officers, the demanding schedule can still wreak havoc on your personal

life.

There are many ways officers choose to deal with the

stress that comes with working long hours in a jail and not

all are positive. . . .

Once, when I was on a hospital run (that's when officers

take an inmate from jail to a hospital, usually to the emergency room); the officers (there were about eight of us from

C-95, AMKC) were sitting in the Kings County Hospital

emergency room. It was about three in the morning, and we

were all conversing.

One officer, who was known in C-95

for working overtime, was bragging about all the overtime

he had been working. He went on about how he worked

overtime whenever he could get it. He told us how he

would regularly work sixteen hours a day almost everyday,

which meant he worked overtime five out of seven days

almost every week.

He bragged about how he could get any

post he wanted on overtime because the captains and tour

commanders (ADWs) counted on him to work overtime

and really valued his service. He talked about how big his

checks were and how he could buy any car he wanted for

cash and so on.

1

The Koonce book has no images illustrating the text. For design and informational purposes, relevant images have been added on this page and captioned by the webmaster. This older gentleman was a civilian patient lying on a

stretcher near by, waiting to be seen. He had been listening

to our conversation. He sat up and asked the officer,

“Do you have children?”

“Yeah, I have two boys,” the officer replied proudly

“How much time do you spend with your boys?” the

older gentleman asked.

The officer, now on the defensive shot back, “Oh, I

spend a lot of time with my boys.”

The older gentleman then asked, “How do you spend

a lot of time with your boys when you just said you work

sixteen hours a day almost everyday?”

The officer began to try to explain by saying, “Well,

whenever I get home, no matter what time it is, I wake them

up and spend about an hour with them, and I spend about an

hour with them before I go to work,”

The older gentleman then said, “Okay, so that’s about

two hours a day with your boys, and sixteen or more hours

are devoted to corrections.”

Our area of the E.R. went silent as we realized how

much of himself he had given to the department and how

little he had given to his children. In less than one minute

this officer went from being a big man, working big hours,

and making big money to being a misguided father who had

not yet gotten his priorities straight. . . .

Too Eager

From the twenty-fifth chapter: One day during count time, Officer Zeus instructed the

inmates to stand by their beds to be counted. One inmate

ignored Zeus’s instructions and stayed in the dayroom reading a magazine. Officer Zeus went into the dayroom and

ordered the inmate to go stand by his bed for the count. The

inmate refused to leave the dayroom, and he and Officer

Zeus began to argue. One thing led to another, and a fighting ensued.

The inmate was no match for Officer Zeus who easily

defeated him. Three other inmates, seeing their fellow

inmate losing the fight, jumped in and joined the fight

However, the four inmates were no match for Zeus; he was

able to single-handedly beat all four of the inmates into submission. By the time the riot squad arrived, Officer Zeus had the entire situation under control.

Rumors of the fight quickly began to circulate throughout the jail. As the weeks went on, Officer Zeus was

involved in two more fights with inmates and each time he emerged victorious.

Officer Zeus became the talk of the jail

among the officers and inmates. . . . the supervisors were talking about him,

as well. Many of them felt that Officer Zeus’s popularity was a good thing, and the jail needed officers like Zeus to get tough with the inmates. Many also felt that Officer.

Zeus’s popularity provided a needed boost to the morale of

the officers in the jail.

The supervisors wanted to use Officer Zeus’s notoriety to their advantage, so they began changing his post to areas like the Receiving Room or Movement Control, where he

would be one of the officers first to respond to any alarm

throughout the jail. He would often be assigned to the probe

team, an assignment that was usually given to officers that

had several years of experience. This was very unusual

because Officer Zeus was getting these preferred assignments with only a few months’ experience as a correction

officer. . . . .

In the

months that followed, Officer Zeus responded to many

alarms and battled with dozens of inmates. His supervisors

encouraged him to be aggressive with the inmates, and they

often praised his actions at the officers’ roll calls.

Zeus felt like he was on top of the world. He thought

that he had finally found his niche, the one thing that he was

good at. He was proud that in less than a year he had made

a name for himself.

Three days before he was scheduled to complete his

probationary period, Officer Zeus was terminated. They

told him he was being terminated because he had too many

uses of force.

Many officers mistakenly believe that their job is

secure if their immediate supervisors are happy with their

job performance. This is not always the case. . . .

When the committee saw Officer Zeus’s file come

cross their desks, with the records of his involvement in

dozens of uses of force, and compared that to the average

recruit that was involved in only four uses of force, Zeus

probably stood out like a sore thumb. They probably

assumed that Zeus was a hot head or quick tempered. They

probably decided that it was better to terminate Officer

Zeus rather than keep him and have to defend him and his

record in a lawsuit in the future. The committee had no way

of knowing that the supervisors were calling on him to

engage in these uses of force. . . . .

|