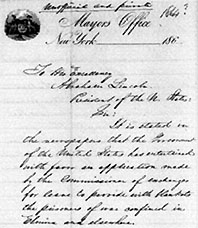

Among the minor mysteries in Lincoln's presidential papers is a handwritten letter from C. Godfrey Gunther on mayoral stationery but labeled "Unofficial and private." Undated by Gunther, the letter carries a notation apparently added by some archivist along the way: "1864?"

The communication concerned getting blankets to prisoners of war in the Finger Lakes city of Elmira before the harsh upstate winter gripped the camp that had received its first Confederate POWs in the summer of 1864.

Gunther wrote that a group of citizen "impelled by motives of humanity" had asked him to head a public appeal to Lincoln to allow a cargo of cotton from the South to enter New York City where the blankets would be made and shipped to Elmira. But the mayor explained he declined to head the open petition drive because he viewed any such "public application . . . to be unnecessary" since

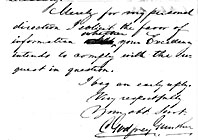

The letter concludes by asking the President to let the mayor know ("merely for my personal direction") if Lincoln intended to grant the request. An intriguing question arises relative to the timing of the letter and its seeming effort to be "unofficial and private." If written prior to Election Day, Nov. 8, 1964, was it a sincere attempt by Gunther to remove the blanket project from the realm of Presidential politics? Or was it a ploy to have Lincoln make known his intent early enough, one way or the other, so that Peace Democrats promoting the blanket project could take credit for initiating it or, alternately, attack the President for thwarting it? If written after Lincoln had won re-election, did its "unofficial and private" guise provide a mechanism for the Peace Democrat mayor to support the blanket project without appearing to beg a kindness from a President whom some of Gunther's supporters regarded as a mongrelizer and tyrant?

The answers to questions raised by the existence of the undated "unofficial and private" letter from Gunther to Lincoln about the Elmira POWs blanket project may never be known. But the devastating toll exacted on the prisoners by the camp's inhumane conditions is known. Lonnie R. Speer, in his Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War excerpted extensively elsewhere on this NYCHS web site, notes that, unlike the other POW facilities around the country up to that time, it didn't start out as a fairly acceptable place of confinement and then slowly degenerate into a concentration camp; Elmira Prison was one from the very day it began. In the 13 months that the camp operated, nearly 3,000 Confederates died there. They are buried in a special section of Elmira's Woodlawn National Cemetery where Unionist dead also are buried. So are other Americans who fought in later wars involving United States forces. The cemetery is situated next to the grounds of Elmira Correctional Facility, a New York State Department of Correctional Services prison.

John W. Jones, retained to handle the Elmira POW burials, had been the sexton of the Baptist Church in Elmira for decades. John, with his brothers Charles and George, escaped from Southern slavery in 1843 and came to Elmira from Leesburg, Va., after walking the hundreds of miles in 14 days, except eight miles when they got a ride from a farmer. Many a Southern family searching for the grave of a fallen Confederate relative has been grateful for the extraordinary care, respect and record-keeping diligence with which Jones went about his burial duties. Because of his faithful service, they have been able to track down and visit their kin's grave. The approximately 3,000 Confederate POW burials in Woodlawn were performed without benefit of services or ceremonies of any kind, quite unlike what was accorded one Union casualty throughout New York and other Northern states: Abraham Lincoln, whose funeral occasioned such public mourning as never seen before and rarely since. *Copyright on text. © 2001 by the New York Correction History Society and Thomas C. McCarthy. Noncommercial use of text permitted with citation of the society and/or its web site www.correctionhistory.org.[Top of Page] [List of Mayor Gunther Bio Pages] [Next Mayor Gunther Bio Page] [Previous Mayor Gunther Bio Page] [NYCHS Home Page] [Chronicles Starter Page] |