Excerpts below from Puppies Behind Bars Summer 2001 newsletter article entitled

Goord Vibrations

Glenn Goord, the commissioner of New

York’s Department of Correctional

Services, kicks off a question and answer

session by telling his fellow Puppies Behind Bars (PBB) board member,

Elise O’Shaughnessy, “The day I’m having today,

I might announce my retirement during this interview.”

If you’re commissioner of the nation’s

fourth-largest state prison system, you’re going

to have moments like that. But on the whole

Goord seems to thrive

in his job, talking with

enthusiasm about what

he has learned in his

28 years of state service.

XXX

XXX

|

|

Ms. Judy Goldman walks with the assistance of Lucie, the first guide

dog trained at Bedford Hills, the facility at which the program was introduced in the DPCS system. The image is cropped and smaller version of one in an article in a story in the August 2004 issue of DOCS Today. Click image to access issue.

|

| His seat on the

PBB board is a telling

vote of confidence,

and Goord already had

begun exploring programs

along the same

lines when PBB president

Gloria Gilbert

Stoga arrived at his

office four years ago to

ask for his help.

“She

came in, nervous, not

knowing what the system’s

perception would

be,” he recalls. “Then my dog came in.” Goord’s

yellow lab, Mogul, is in the office with him nearly

every day, and, as he often insists, is an integral part

of his operation.

“I think Puppies Behind Bars has done an outstanding

job,” he says, adding with typically self-deprecating

dead-pan humor that “I also like to

think that having my support has made a difference.

I picked places [the Bedford Hills and Fishkill prisons,

to start with] where I knew it would be a

success. For instance at Fishkill, the superintendent

was Wayne Strack and he was a dog person.”

PBB: Aside from the fact that the commissioner

has a yellow lab and Wayne Strack is a dog person,

why do you think this program works so

well?

GG: . . . Working with the dogs, the inmates are

renewing their feelings of compassion and feelings

of love. Those are very positive things that we

want to send people back out to the community

with. The community’s perspective is that they’ve

lost those things, they’ve lost those values.

I hate to sound corny, but what’s more positive than a person’s love for their animals or

animals in general? If the inmates [PBB

has chosen] didn’t have those values, they

now have them, and if they had them, the

program has renewed those values....

XXX

XXX

|

|

Inmate Jesse Mulligan (left) tends to Power while inmate

Heriberto Rivera’s attention is focused on Noll. Image is a smaller version of one in the cover story of the June 2003 issue of DOCS Today. Click image to access issue.

|

| The

effect hasn’t been just on our inmate handlers,

either. The effect has been on every

person the puppies come in contact with.

PBB: When you talk about rehabilitation

and restoration, what determines the success

or failure of an effort like Puppies

Behind Bars?

GG: Creating a good product for the consumers

that are getting the puppies—that’s

very important to us. And the second piece

of it, from where I sit, are statistics that

over time show that these people go back

to the community where they came from

and don’t come back to my system and are

arrest-free. The problem in my business is

that a person’s failure in the community is

sometimes looked at as a system's failure,

but when you’re dealing with human

beings, you cannot just blame the system

for that person’s failure. . . .

PBB: What makes the difference between

someone the program works for and someone

it doesn’t work for?

GG: . . . I think we have found that the

inmates certainly have been very trouble

free while they’re involved with their new

responsibilities of taking care of the puppies.

The other positive things are that it

gives the community some glimpse into

what goes on in the prison system. It

gives not only the inmates involved in the

program, and the employees involved in

the program, it gives all my employees

some sense of pride that inmates are giving

back to the community. I think that’s very

important. But it’s a hard question, my

friend.

PBB: We only ask the hard questions.

You’ve devoted a large part of your life to

a very difficult job, both hands-on and in

the bureaucracy. Looking at it from both

sides, what has been the toughest challenge

of your career?

XXX

XXX

|

|

Puppies Behind Bars pups pose (well, sort of . . . ) with inmate trainers and PBB instructor Carl Rothe (2nd from right) at Mid-Orange Correctional Facility. Image is cropped and smaller version of one in the cover story of the June 2003 issue of DOCS Today. Click image to access issue.

|

| GG: . . . The biggest challenge has

always been—and continues to be—to keep

the balance of care, custody, and control

while you’re creating an environment where

inmates can get opportunities to fix their

problems, and then working on programs

for better transition [to society] and not

returning to the system. . . . So I guess the

hardest part of the job is creating an environment

in these institutions where I can do

all the things [rehabilitation and restoration]

that I just talked to you about. Because in

environments where inmates don’t feel safe

and employees don’t feel safe, nothing else

happens. . . .

(The biggest problem, by the way,

[when the auditors come to my central

office] that my people are most concerned

about, is how do they explain the dog

[Mogul]. And I say, “The dog stays. You

have to explain to the auditors that the dog

is an integral part of keeping the commissioner

focused and the dog is just part of

the system.”)...

Excerpts below from Puppies Behind Bars web site history page entitled

A New Leash on Life:

How We Got Started

XXX

XXX

|

|

Above: Gloria Gilbert Stoga whose adoption of Arrow led eventually to the founding of Puppies Behind Bars. The image above is a version of one with the PBB web site article by her excerpted here. Click image to access.

|

|

In 1990, my husband and I adopted a Labrador Retriever from one of North America's most prestigious guide-dog schools, Guiding Eyes for the Blind in Yorktown Heights, NY. "Arrow" had been on his way to becoming a guide dog but was released from the program for medical reasons.

Upon adopting Arrow, I began reading about the special breeding and training that had gone into him and was amazed to discover how much time, effort, love, and money ($25,000) is behind each guide dog..

A large part of the extraordinary effort that goes into these special dogs comes from "puppy raisers" -- individuals or families who take specially bred puppies into their homes when the pups are just eight weeks old and who spend the next sixteen months teaching them basic obedience skills and socializing them to enter the world at large. Socializing the dogs is actually the main component of a puppy raiser's task, for socialization is what helps these dogs become confident. . .

After sixteen months, the dogs leave their puppy raisers, return to the guide -dog school from which they came, and are given a series of tests to determine their level of confidence. If they pass the tests, they go on to five or six months of professional guide-dog training.

XXX

XXX

|

|

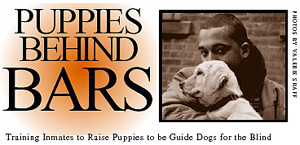

Above: Part of banner across top of Puppies Behind Bars home page. Click to access.

|

|

Dr. Thomas Lane, a vet in Florida, thought that prison inmates would make excellent puppy raisers, and started the first guide-dog/prison program. Not only do inmates have unlimited time to spend with the puppies, but they benefit from the responsibility of being puppy raisers in ways that are especially important to their rehabilitation . . . .

After several months of research, I decided to leave my job on New York Mayor Guiliani's Youth Empowerment Services Commission and devote myself full-time to founding a non-profit organization dedicated to training prison inmates to raise puppies to be guide dogs for the blind.

Puppies Behind Bars, Inc. formally came into existence in July 1997, and we initiated the program at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in November 1997. We began with five puppies in the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, New York State's only maximum-security prison for women, and now work in five correctional facilities raising approximately 50 puppies.

XXX

XXX

|

|

PBB founder Gloria Gilbert Stoga, in gray shirt, leads open-air training drill at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility. Image is cropped and smaller version of one that appeared with an article by Sarah Hodgson in the Sept./Oct. 2005 issue of Bedford Magazine that serves Westchester and Fairfield. Its home page is at www.bedfordmagazine.com The article can be accessed at her SimpySarah.com web site by clicking the image.

|

| The pups live in the cells with their primary raisers, go to classes administered by Puppies Behind Bars once a week, and are furloughed two or three weekends a month to 'puppy sitters' who take the dogs into their homes in order to expose them to things they won't experience in prison. . . .

The puppies live in prison for sixteen months, after which they are tested to determine their suitability for guide-dog work. If they are deemed suitable, Puppies Behind Bars returns them to the guide-dog schools from where they came. If they do not continue on the track to guide work, Puppies Behind Bars donates them to families with blind children. In either case, these puppies, raised in such a unique environment, spend their lives as companions to people who need them. . . .

The puppies have affected the lives not only of their puppy raisers, but of virtually all the inmates and staff at the prison. It is literally impossible to walk a puppy around without being stopped by inmates who want to pet the dogs or who want to just say 'hi' to them, and I am constantly being approached by corrections officers and senior staff who ask me about the puppies' training. . . .

If you are interested in becoming a weekend puppy sitter . . . or having copies of our newsletter sent to someone you know, please call Puppies Behind Bars at 212-680-9562 or email us at info@puppiesbehindbars.com

Thank you.

Gloria Gilbert Stoga,

President,

Puppies Behind Bars, Inc.

[10 East 40th Street, Floor 19

New York, NY 10016]

|