Excerpted and abridged by NYCHS from:

Introduction (Pages 7 -- 10)

The most important development in correctional philosophy and practice in the first half of

the 19th century was the widespread substitution, in most civilized lands, of imprisonment for

corporal punishment as the usual method of punishing convicted offenders. The only subsequent

achievement of comparable magnitude was the synthesis of administrative experience and

creative imagination, which we have come to know as the reformatory movement. This was

the second great stage in the improvement of correctional philosophy and practice in the

United States. . . . .

From its foundation in 1876, the Elmira Reformatory developed in the direction of its object

(to a “crime hospital” for the morally depraved) since the day of its dedication.

XXX

XXX

|

|

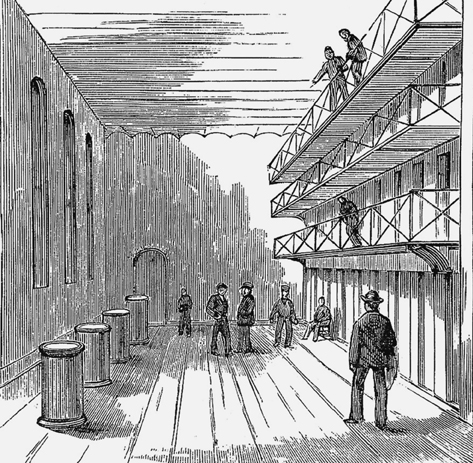

"The south side solitary cells pavilion (division S) was also surrounded by turrets. There were four

floors (tiers) with 8 cells on a floor, for a total of 32 cells. The cells were 8 feet square on the floor

and 9 feet high with 576 cubic feet of space. The north side trades school building contained

work spaces for carpentry, blacksmithing, bricklaying, and so forth. . . . ."Reprinted with permission from Page 27 of Images of

America:

Elmira

Reformatory, by Dr. William G. Hinkle & Bruce Whitmarsh. Available from Arcadia Publishing online or by calling 888-313-2665.

|

|

By 1890, there was

widespread public recognition and acceptance of the principles of pathological theories of crime

and the treatment of criminals. These principles became the cornerstone of the reformatory’s

system of prison discipline. . . . .

For the first decade of its existence, the reformatory was regarded as an experiment in criminology,

a homogenous system of a number of radical theories developed in the minds of men who had formed

a proper regard for the problem of crime. A scientific investigation of their subject convinced them

that the punishment to deter philosophy encouraged rather than discouraged the formation of a

criminal class. They took the view that the criminal was most often a criminal through heredity,

environment, or mental and physical defects. They sought to correct those defects and, in the process,

came to the rational conclusion that there were grades of criminals—first offenders, recidivists,

and incorrigibles—whose treatment might profitably be tempered to their gradation. In 1890, the

inmates of the reformatory were, as from the beginning, classified into three grades, which were

designated as the first, second, and third.

XXX

XXX

|

|

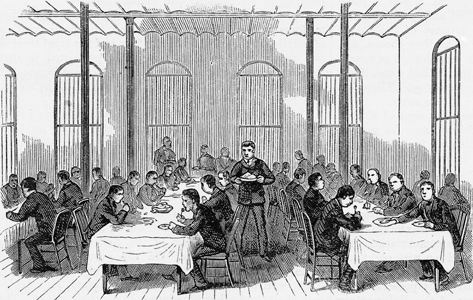

"The meals for nearly 1,500 people were all prepared in the domestic building. The basement

included a large kitchen in which inmates’ soups, stews, and hash were prepared in great steamheated

kettles. Nearly three-fourths of the inmates ate in their cells. Breakfast was carried to

them in pans on large wooden trays, and dinner was delivered on a slide they passed on the way

to their cells." Reprinted with permission from Page 42 of Images of

America:

Elmira

Reformatory, by Dr. William G. Hinkle & Bruce Whitmarsh. Available from Arcadia Publishing online or by calling 888-313-2665.

|

|

Comparing crime to a disease, it was believed that like the patient suffering from a physical

illness, prisoners should be kept under treatment until cured of their criminal propensities. The

indeterminate sentence was thus established as a basic principle. The statute provided for this fell

short of making the sentence strictly indeterminate by forbidding the incarceration of the offender

beyond his maximum term of imprisonment. Convalescence was construed to be moral, intellectual,

and physical capability to earn a living and to become a law-abiding productive member of society.

The reformatory prescription consisted of a trinity of Ms—mental, moral, and manual training.

These ingredients varied based on the needs of the patient as developed in diagnosis and, sometimes,

by the invention of better methods and/or the intervention of new laws.

. . .

In the course of its history, the guiding philosophy at Elmira was always reform. However, the

type of reform changed from the distinct emphasis on moral and intellectual reform (between

1876 and 1891) to pathological reform (from 1892 until early in the 20th century).

XXX

XXX

|

|

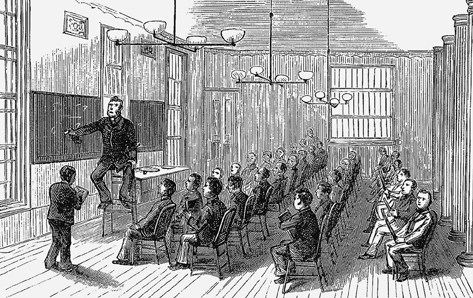

"While the various industrial classes in the new trades school building were introduced in January

1886, the educational program was established in 1878. Initially, classes were arranged in the

evening so as not to interfere with the hours of labor and included all the men who were able

to attend. The three-times-a-week recitations, which were attended by all inmates, were divided

into six large classes overseen by experienced teachers. The whole educational program, under

the supervision of the Reverend Dr. D.R. Ford of Elmira College, covered two years.

" Reprinted with permission from Page 68 of Images of

America:

Elmira

Reformatory, by Dr. William G. Hinkle & Bruce Whitmarsh. Available from Arcadia Publishing online or by calling 888-313-2665.

|

|

Unfortunately,

Elmira is better known for its focus on pathological reform, a school of thought that has been

all but completely discredited. Consequently, the groundbreaking work done between 1876 and

1890 has been largely forgotten.

Indeed, it is this early period that deserves reexamination to the

extent that it was guided by theoretical assumptions that have, in fact, stood the test of time and

empirical scrutiny, especially the assumption that education will reduce criminal recidivism.

Because the Elmira Reformatory was the first notable institution that embodied all the principles

of the reformatory system and was devoted exclusively to youthful offenders, it was frequently

asserted that the reformatory was a peculiarly American institution.

However, in 1854, Sir Walter

Crofton (1815–1897) based his system of convict discipline upon Captain Maconochie’s plan.

The Irish System, as it came to be known, was devised and inaugurated in Ireland from 1854 to

1862. Crofton brought the Irish prisons into a state far superior to those of England, introducing,

besides reformatory treatment, a four-stage graduated release component. . . .

XXX

XXX

|

|

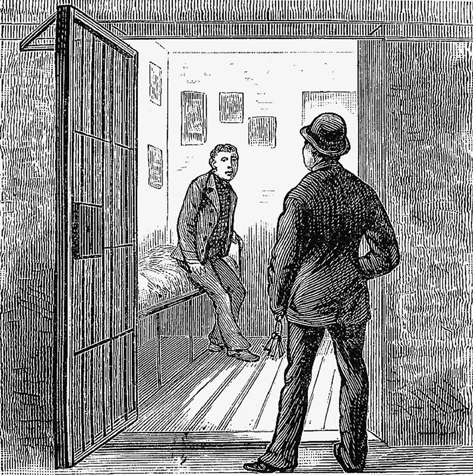

"The hall keeper had oversight of the cells, rooms, corridors, hospital, and patients; clothing and

bedding; the admission and discharge of all prisoners; communication between inmates and all

persons outside of the reformatory, including family and friends; and of the keys, weapons, and

institutional stores in general." Reprinted with permission from Page 114 of Images of

America:

Elmira

Reformatory, by Dr. William G. Hinkle & Bruce Whitmarsh. Available from Arcadia Publishing online or by calling 888-313-2665.

|

|

What the American reformers did was to work out the

first complete synthesis of Maconochie and Crofton’s enlightened principles and to apply them

in an institution that received inmates between 16 and 30 years of age.

The Elmira Reformatory’s first superintendent, Zebulon Brockway, began his 50 years of prison

employment as a clerk at the Wethersfield State Prison in Connecticut. The Wethersfield facility

had been strongly influenced by a family of prison wardens named the Pilsburys . . . . Brockway believed that the stringent

discipline maintained by the Pilsburys was indispensable in any really effective reconstructive

formation of the character of adult criminals.

By chapter 408 of the laws of 1869, a reformatory was authorized to receive male offenders

between the ages of 16 and 30. The following year, the first convention of the American Prison

Association met in Cincinnati. Zebulon Brockway presented a paper based on the Irish system,

which dealt with the idea of an indeterminate sentence and the possibilities of a system of parole.

The prison reformers meeting in Cincinnati urged New York to adopt Brockway’s proposal at

Elmira. When the Elmira Reformatory opened in 1876, Brockway was appointed superintendent.

|

To access Chemung County History Museum, click its image below:

|

|

Founded in 1923, the Chemung County Historical Society is a non-profit educational institution dedicated to the collection, preservation, and presentation of the history of the Chemung Valley region.

First chartered by New York State in 1947, today CCHS operates two cultural repositories, the Chemung Valley History Museum and the Booth Library. We are the largest general history museum in our region.

The Chemung Valley History Museum is situated at 415 East Water Street in the heart of downtown Elmira, NY, about 15 miles east of Corning, 30 miles south of Ithaca, and 55 miles west of Binghamton.

Phone: (607) 734-4167. Email: cchs@chemungvalleymuseum.org

|

|

For Chemung County History Museum on facebook, click its FB logo below:

|

|

For Brockway, the causes of crime were to be found in class differences, especially with respect to

morality. “The quality of being that constitutes a criminal cannot be clearly known,” he wrote,

“until observed as belonging to the class from which criminals come.”

. . . . The height of the excitement about (and the brightest hopes for) reformatories occurred in the

1870s and 1880s, when numerous state and federal reformatories were built. By 1888, every effort

was made by reformatory officials to estimate the rate of recidivism among the 1,722 inmates

paroled since the opening of the reformatory in 1876 through September 30, 1887.

. . . . The board

of managers proudly declared that the public enjoyed protection to the extent of “90 percent”

of the whole number received and treated, and, in regard to men paroled, over 80 percent were

considered as “probable reformations.”

To the extent that these statistics were accurate, they would

indicate an extraordinarily low cumulative recidivism rate of 10 percent for the first 11 years of

the existence of the reformatory. . . .

Although by 1890 the population at the reformatory had exceeded the limits outlined by

the first planning commission (500 was the original population limit), there had been some

modification of the general scheme of treatment of the “patients.” Nevertheless, there had been

a specialization of function and a singleness of direction. Moral, mental, and manual training

had been systematically coordinated with the end in view of producing practical, self-helping,

and self-governing citizens. . . . .

|

WEBMASTER NOTE: The New York Correction History site appreciates and acknowledges Arcadia Publishing for permitting it to craft and post this presentation of illustrations and introductory text excerpted from Images of

America:

Elmira

Reformatory, by Dr. William G. Hinkle & Bruce Whitmarsh. This presentation features five of the six illustrations among the book's 200 images. The other 194 images are photos so excellent that choosing from among them which to present here proved most difficult. So we decided to select only the sketches.

|

Also see

|