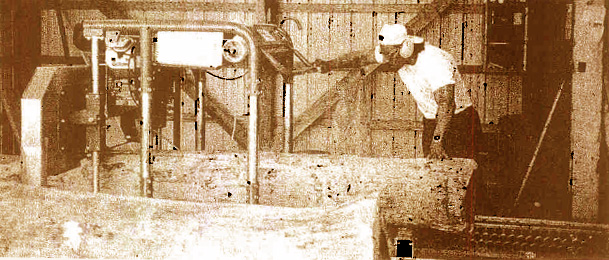

Mid-OrangeMid-Orange, a medium-security prison housing 750 adult males, occupies 740 rolling country acres in the foothills of the picturesque Ramapo Mountains in southern Orange County, about 60 miles northwest of New York City. The property includes frontage on Wickham Lake, where employees often picnic. Laid out among bucolic wetland tracts and woods are more than 60 buildings. One, the Manor House, is 160 years old. Most date from the early 1930s, when the institution opened as a boys' reformatory, and are two-story, red brick structures with maroon trim. Stone walls intersect broad lawns where geese flock and deer graze. Picnic tables stand among apple trees; grapes grow outside the superintendent's house. A public road winds through the property. Most of this splendor is off-limits to inmates, who are generally restricted to one of two fenced areas: the main compound and, about a quarter-mile distant, H-Section. H-Section is honor housing, with dormitories and small rooms for approximately 130 "outside-cleared" inmates. It is H-Section that provides the inmate manpower for Mid-Orange's impressive program of community service. Crews of inmates under Officer supervision are regularly placed at the service of other state agencies, doing maintenance work at the Bear Mountain State Park and on the state Thruway, for example. Others help out local governments and not-for-profit organizations: inmates paint and shovel snow for local churches, clear brush and debris from roadsides and maintain local cemeteries and senior citizen centers. Inmates clean up Warwick's Cascade Park and Little League baseball fields. Mid-Orange's staff and inmates also are always ready to respond in emergencies. Two recent examples include aiding firelighters at West Point and filling and piling sandbags to hold back flood-waters rising around the town of Greenwood Lake. Forty to 45 men work in the Corcraft (Correctional Industries) modular housing shop just outside the main compound. The shop, when it started production in 1985, was the first correctional program of its kind in the nation (since then, it has been copied in several other states). It was introduced specifically to meet DOCS' need for new Family Reunion Program units.

Besides modular units, Mid-Orange now produces the blue barricades used by the New York City Police Department to block parade routes and crime scenes. For a short period in the mid-'90s, the shop manufactured modular cells for S-blocks. A mini-city corrections system in the suburbs The Mid-Orange facility is one of three Orange County farmland properties bought by the New York City Department of Correction in the early years of the 20th century. In 1916, a property in New Hampton became a city-run reformatory for boys. The reformatory was later taken over by the state and still later, in the 1970's, it was converted to a forensic psychiatric hospital to replace the old Matteawan asylum in Fishkill. Another property in nearby Chester was operated as a farm colony for women offenders. Today, it is a shelter for homeless New York City men. The Warwick property on which Mid-Orange is located was purchased after World War I. An early plan to establish a 500-bed hospital for drug addicts was never realized. Records are scant, but the site seems to have been used at times to house inebriates and addicts and at other times as an "honor colony" for small numbers of well-behaved New Hampton reformatory prisoners. The 740-acre property was under-utilized until 1932, when it was transferred to the state in a trade. The demise of the House of Refuge To understand the trade, we have to go back to 1825. That year, a group of private citizens established a House of Refuge in New York City. It was created specifically to provide a place of detention for juveniles, who until then were housed along-side adult criminals. It was the first children's reformatory in the U.S. and was intended for young vagrants, pickpockets and beggars of both sexes generally aged from about nine or 10 up to 15. In 1854, after several relocations, the House of Refuge settled on Randall's Island in the East River. Toward the end of the 19th century, a vigorous campaign began for the reform of the reformatories. The Randall's Island House of Refuge and its imitators had performed a vital public service in separating children from the adult justice system, but there was little else to praise. With no other models to look to, Randall's Island had copied the forbidding architecture and rigid routines of the prison system, which later generations regarded as ill-fitting a "refuge" for children. That wasn't all that was wrong. Soon after the turn of the century, an investigation revealed instances of extremely brutal treatment and severe discipline. Clothing was shabby and inadequate, the diet was poor, and the coed arrangement allowed the development of "unwholesome relationships." The state Legislature acted to improve the situation. First, in 1904, it moved the girls to Hudson. Next, it laid plans to find a wholesome place in the country for the boys. A training school would be erected on the cottage plan, as recommended by reformers, with the boys supervised by "house parents" so as to approximate normal family life.

An integral part of the programming at Queensboro is the on-site comprehensive participation of local community agencies that specialize in providing assorted transitional services. A new commission found a site near Vassar College, but the women's college did not want delinquent boys as neighbors and Poughkeepsie was ruled out. At last, another site in Yorktown Heights, Westchester County, was found and purchased in 1908. Construction got underway but was suspended pending investigation of a claim that siting the institution so near the Croton watershed would endanger the New York City water supply. The claim was refuted by both the city and state health commissioners, but influential parties continued to fight the Yorktown Heights site. The Legislature responded to the pressure by turning dilatory and stingy with appropriations, hampering a full resumption of construction. Even after the appointment of a Superintendent in 1912, nothing seemed to happen. Disgusted, the Superintendent resigned in 1915. Two years later, the project was abandoned. The idea was resurrected in 1929, when the city of New York expressed an interest in acquiring Randall's Island, about equidistant from Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx, to construct a Triborough Bridge. The city had something to offer in return: the under-utilized property in Warwick. The trade was arranged. The state would build the long-sought training school, to be managed by the Department of Social Welfare (later renamed Social Services). The state would also use the opportunity to undo its mistake of several years previous. That was when, not wanting to leaven beds empty after the girls were removed, it had authorized the House of Refuge to take 16- and 17-year olds, whose presence was not in the best interest of the younger boys. The 12-15 year-olds would be placed in the training school cottages. For the older boys, a new institution - with cells - would be built in Coxsackie to be managed by the [NYS] Department of Correction. Building the training school The State Training School for Boys officially opened on July 1 (the first day of the fiscal year), 1932. By this date, though, nearly 200 House of Refuge boys were already on site. They had been brought up a few at a time starting in June 1930 to assist with construction and begin working the farm.

Building for the new training school was largely completed by 1934. The main section consisted of housing and program buildings. There were 16 two-story, L- shaped cottages. The ground floor contained 12 individual rooms on one wing of the L, with the other wing open and holding about 20 bunk beds. Upstairs were apartments for the cottage parents, usually married couples, who acted as "guides, mentors and supervisors." The cottage parents worked long hours, from about 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., when a supervisor came on duty and stationed himself at the joint of the L (where a Correction Officer is stationed today). For regular days off and vacations, the school employed "relief couples" (their term) who rotated around the cottages, using the second upstairs apartment. Nearby were program buildings. The largest structure was actually several attached buildings: the long vocational building with saw-tooth roof, the chapel (now the messhall), the power plant (whose obsolete old generators are now polished and maintained as though in a museum) and the laundry (now used by the maintenance staff). There was an academic building (still the school today) and a gymnasium/auditorium building. Two two-story, U-shaped buildings (now Mid-Orange's honor housing section) were set apart from the main group. The larger of the two, with an arched stone entryway, contained offices, the hospital, the reception unit with 16 rooms, and a kitchen and dining room. The smaller U-building was quarantine unit, with 22 cells where unruly boys could be isolated. The staff residential group contained the Superintendent's residence, the Manor House (divided into apartments), another building with single rooms and the staff dining room (later converted into the administration building). A fourth group held the farm buildings: cow and horse barns, greenhouses, a chicken house, a milk house and various storage facilities. Farming, once extensive at Warwick, was discontinued in the 1960s. One of the buildings is now used for staff training and others are used for vehicles and storage. Training School program The Training School operated for 45 years. It had a capacity of 500, but generally held about 400 boys. They were aged 13 through 15 years but often included older boys, some as old as 19, who lied about their ages to avoid prison terms. The program included academic and vocational training and work assignments in the kitchen, maintenance and grounds-keeping, or on the farm.

Sometime boys broke into summer residences, sometimes they managed to steal a car (one boy picked the educations director's pocket, got his keys and drove off). Usually, though, they were picked up quickly by male cottage parents taking turns on "breeze duty." Official state descriptions of the training school stressed the wholesome, family environment and the individual care given by a nurturing staff of teachers, social workers, psychologists and cottage parents. Another perspective is offered in Claude Brown's Manchild in the Promised Land . . . . Deinstitutionalization hits Warwick In 1971, Warwick and the other training schools for youths were transferred from the state Department of Social Services to the Division for Youth (DFY). The switch was part of a general movement away from traditional institutional programs - including prisons, reformatories and hospitals for the insane and the retarded - that had been gathering momentum for about 10 years. Almost from its creation, DFY had an anti-institution bias. DFY was born in 1955 as part of the [NYS] Department of Correction, but was separated from corrections in 1960. The newly independent DFY did not include any institutional programs: its major thrust was the creation of alternative programs to spare as many youths as possible the scars of exposure to the DSS training schools. When DFY was given responsibility for the training schools in 1971, it was with the expectation that their utilization would be reduced to a minimum. Within five years, DFY closed three of the training schools entirely. Each of them — Warwick, Hudson and Otisville - would immediately be absorbed by the bed-hungry DOCS.

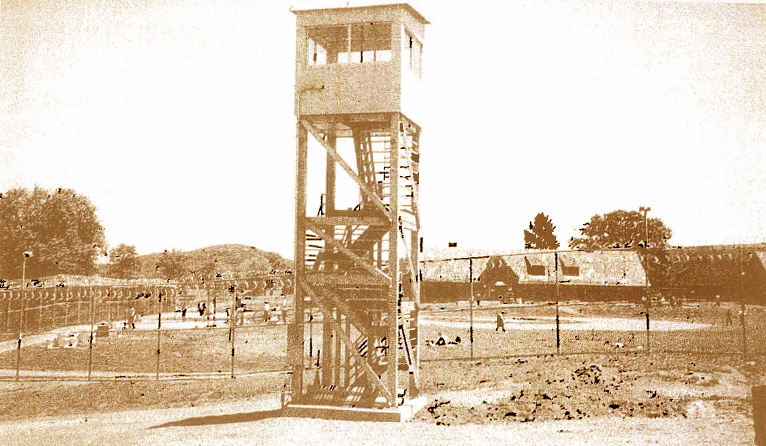

In 1976, the training school at Warwick closed. The property was transferred from DFY to DOCS in October. The Department erected fences around the two inmate housing areas. The two H-Section buildings were modified for use as honor housing, and the former staff kitchen and dining building became the new administration building. The first inmates arrived on June 29, 1977. It took about six months to reach the planned capacity of 400. Then, starting in 1981, as the effects of the war on drugs were being felt systemwide, the new facility's population began to rise above the planned limit. Capacity was increased by double-bunking and placing inmates in the upstairs apartments and in the gymnasium. By the summer of 1989, nearly 1,000 men were housed at Mid-Orange. The next year, with the completion of several new "cookie cutter" facilities upstate, Mid-Orange was able to scale the census back to 750, where it has remained. Diverse program offerings Mid-Orange features a wide range of effective programs. In addition to the Department's core activities (work assignments, academic and vocational education, Alcohol and Substance Abuse Treatment and recreation), Mid-Orange offers special programs for veterans and Hispanic inmates. A course taught by outside volunteers helps inmates to be better parents; inmates also work to create a better future for others through frank discussions with at-risk area teens about drug use, peer pressure and life styles through the Youth Assistance Program. Other inmates in the Prisoners' AIDS Counseling and Education (PACE) program travel about the facility to provide factual information about AIDS and combat irrational prejudices that in the past led to ostracism and mistreatment of those suffering from the disease. Two courses help inmates learn to control anger and aggression. Aggression Replacement Training (ART) is a 12-week course taught by inmate facilitators supervised by DOCS counselors. The Alternative Behavior Course (ABC) consists of eight sessions conducted by volunteers who talk with inmate participants about appropriate responses to anger and stress. A frequent ABC guest, until his death in 1999, was Richard Kiley, the award-winning stage, film and TV actor best known for his Broadway portrayal of Don Quixote in Man of La Mancha. . . . Also relying on volunteers is the Life Skills series of workshops. An average of 75 volunteers a year - doctors, insurance agents, bankers, attorneys, realtors and others - visit Mid-Orange to discuss their specialties and services, helping prepare inmates for release by broadening their perspectives and alerting them to opportunities and pitfalls.

Back in the late 1970s, Mid-Orange was one of the original sites (with Bedford Hills and Hudson) for the Network program, a behavioral modification program emphasizing personal responsibility while drawing on the power of peer support. Network was one of the first therapeutic community programs in New York's prisons. It differed from others (residential ASAT programs and Stay'n Out) in assigning a primary treatment role to Correction Officers. The program was considered successful, but fell victim to budget cuts in 1990, surviving only in Shock Incarceration facilities. In 1999, Stephen J. Chinlund - a former Taconic Superintendent and chairman of the State Commission of Correction who's now the Executive Director of the New York City-based Episcopal Social Services - received permission from Commissioner Goord to reintroduce Network to DOCS prisons. . . . Episcopal Social Services employs Jubilee coordinators (two of whom are graduates of the DOCS Shock program) who sit in on prison programs weekly as advisors. Jubilee Network also offers a post-incarceration component, with meetings at several sites in New York City, for parolees and work release inmates. Return to menu listing NYCHS excerpts of DOCS|TODAY Facility Profiles.

|