Blake F. McKelvey's 1972 A History of Penal and Correctional Institutions in the Rochester Area

[McKelvey pages 6 through 9] O'Reilly's frequent visits to Mackenzie had alerted him to a more serious deficiency in the jail system. Whatever could be said for its administration, certainly the jail was no place for the confinement of children and, starting in 1838, he besieged the legislature with a series of petitions for the establishment of a House of Refuge, similar to one recently opened on Randall's Island at New York, for the separate detention and reformation. of juvenile delinquents. O'Reilly moved to Albany before these petitions brought results, but several of his collaborators, notably Isaac Hills and Frederick P. Backus,

Although limiting its admissions to boys between the ages of eight and sixteen committed by western New York courts, the House of Refuge had to erect a second wing in its second year and by 1851 had an enrollment of 130 housed in seven-foot square dormitories opening from both sides of long corridors extending through the two floors of these wings.

Under the direction of Samuel S. Wood, as first superintendent, a teacher gave elementary instruction to those who could not read or write, while an enterprising contractor directed the work of other boys in making cane chair seats and whips to help defray institutional expenses. The completion of a stockade around the farm made it possible to send some boys out to help produce food for daily consumption. As the population increased the superintendent engaged an assistant, a second teacher and a tailor, in addition to the gatekeeper, farmer, and matron previously employed. Apparently the gatekeeper was the only guard, and most of the household chores were performed by the boys themselves.

A small library and a plunge bath supplied new features in 1852, and the next year saw the opening of a shoe shop and a tailor shop to increase the variety of work assignments available to the boys, who now spent seven hours a day at these tasks, 3.5 hours in school and 1.5 at meals before returning to their dormitories for the night. The addition of new school rooms, new teachers, new work shops, and a new dormitory wing marked the steady growth in numbers to 386 by the close of the first decade. Good reports from some of the 102 boys who had been indentured to farmers, craftsmen, and other guardians added to the board's gratification over its accomplishments. The success of the House of Refuge plus the continued growth of the city, which threatened to overcrowd the county jail, prompted a new move in 1852 to establish a separate institution to house the increasing number of misdemeanants sentenced by the courts. News of the provision of workhouses for the confinement of misdemeanants in both Albany and Erie counties spurred the supervisors of Monroe County to appoint a committee to study the situation. Its recommendation that a workhouse be erected on a 12-acre section of the county poor farm won quick favor, and shortly after the receipt of legislative approval work commenced on its construction on the city's southern border. Built of brick on the Auburn pattern with a cell block to accommodate 96 men and a separate group of cells for 40 women, the Monroe County Workhouse had at its opening in November 1854 a third building ready for the use of contractors eager to employ the inmates at productive tasks. And to head it, the supervisors brought Zebulon Brockway from Albany where he had demonstrated his ability to make the inmates of its almshouse earn their entire expenses. An able administrator and disciplinarian, Brockway faced several new challenges in Rochester. In contrast with the almshouse at Albany, where the inmates were fairly permanent, the commitments to his workhouse in Rochester represented a flowing stream of short timers. The 539 received the first year mounted to 754 in the second, but the number in custody at one time increased from approximately 100 at the close of the first year to 130 twelve months later.

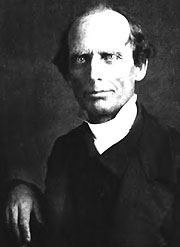

The rapid turnover made the organization of efficient work schedules difficult, and it was not until the third year that returns from the work shops reduced the maintenance costs below $1,000. It was also in that year that Brockway attended a series of revival meetings conducted by Charles G. Finney, who gave a new direction to his energies. Inspired by a new religious zeal, he organized and conducted animated Sabbath school services at the Workhouse. As recalled in his autobiography years later, the inmates quickly responded to Brockway's new approach, singing and praying with gusto, and he was able to discharge some of them with a warm sense of having contributed to their redemption, only to see many return a few weeks later with new sentences. Challenged by that second disillusionment, Brockway began to consider the merits of establishing a school to teach the three R's to the many inmates who lacked such skills. His annual reports in the late fifties gave greater attention to the inmates, classifying them as to nationality as well as the nature of their offense, and noting their lack of elementary knowledge and technical skills. In response to his annoyance over the short terms, the managers determined to change the name of the workhouse to a penitentiary in 1858 so that commitments for longer terms could be received under a new state law. By dint of careful management, the several workshops turned out products that netted a small surplus over the maintenance costs for the first time in 1860, but by this time Brockway . . . was absorbed by dreams . . . of indeterminant sentences that would permit a superintendent to hold inmates until they were reformed . . . When the managers of the newly constructed Detroit Workhouse offered to incorporate such a system there, Brockway left Rochester to assume its management. |