Why was the Tombs the

execution site for the only American ever

hanged as a slave trader? By Thomas C. McCarthy [ Black History Month, 2003 ]

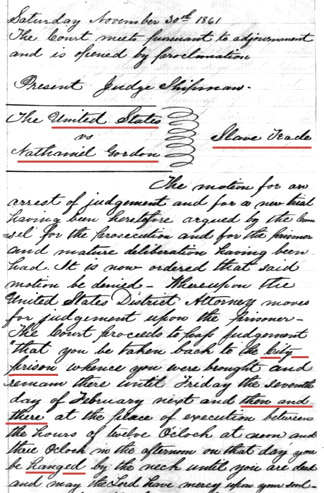

One Hundred and thirty-one years ago this month, the Tombs was the setting for the first and only execution of an American convicted of international slave trading, a capital crime under an 1820 federal piracy law. Use of the City Prison for carrying out the federal death sentence was itself an issue argued in a last-ditch appeal to bar the hanging as illegal because New York State law limited capital punishment to conviction for murder or treason. Having exhausted all other avenues of appeal and with only about 24 hours remaining before the condemned Tombs prisoner, young Captain Nathaniel Gordon of Portland, Maine, was to be marched up the steps of the gallows in the City Prison yard, his lead counsel rushed to Federal Circuit Court on Feb. 20, 1862. The attorney, former New York State Supreme Court Justice and former U.S. Representative Gilbert Dean, had just thought up a novel argument for staying the scheduled execution. But he had not drawn up formal papers. Given the time factor and the life-and-death seriousness of the case, the court put aside other matters on its calendar and accommodated his making the application by way of oral presentation.

Words of sentence

The defense counsel appeared before Federal District Judge William Davis Shipman who on Nov. 30, 1861, had sentenced Gordon with these words: . . . . it is

proper that I should call to your mind the duty of preparing for that event

which will soon terminate your mortal existence, and usher you into the

presence of the Supreme Judge. . . . let your repentance be as humble and

thorough as your errings were great. Do not attempt to

hide its enormity from yourself; think of the cruelty and wickedness of seizing

nearly a thousand fellow beings, who never did you harm, and thrusting them

beneath the decks of a small ship, beneath a burning tropical sun, to die of

disease or suffocation, or

be transported to distant lands, and be consigned, they and their posterity, to

a fate far more cruel than death. Think of the sufferings of the unhappy beings whom you crowded on the

[ship] Erie; of their

helpless agony and terror as you took them from their native land [in West Africa];

and especially think of those who perished under the weights of their miseries

. . . Remember that you showed mercy to none, carrying off, as you did, not

only those of your own sex, but women and helpless children. Do not flatter

yourself that because they belonged to a different race from yourself your

guilt is therefore lessened -- rather fear that it is increased. In the just

and generous heart, the humble and the weak inspire compassion, and call for

pity and forbearance.

As you are soon

to pass into the presence of that God of the black man as well as the white

man, who is no respecter of persons, do not indulge for a moment the thought

that He hears with indifference the cry of the humblest of His children. Do not

imagine that because others shared in the guilt of this enterprise, yours is

thereby diminished; but remember the awful admonition of your Bible, "Though hand join in hand, the wicked shall

not go unpunished." Turn your

thoughts toward Him, who alone can pardon, and who is not deaf to the

supplications of those who seek His mercy. It remains only to pronounce the sentence which the law

affixes to your crime, which is that you be taken back to the City Prison,

whence you were brought, and remain there until Friday, the 7th day of February

next, and then and there, the place of execution, between the hours of 12

o'clock at noon and 3 o'clock in the afternoon on that day, be hanged by the

neck until you are dead, and may the Lord have mercy upon your soul.

Presidential reprieve, not commutation

On Feb. 4, 1862, the President refused to grant a

commutation but issued a proclamation granting a temporary stay of execution.

Setting Feb. 21 as the new date, it read, in part: . . . And whereas, it has seemed to me probable that the

unsuccessful application made for the commutation of his sentence, may have

prevented the said Nathaniel Gordon from making the necessary preparations for

the awful change which awaits him. In granting this respite, it becomes my painful duty to admonish the prisoner that, relinquishing all expectation of pardon by Human Authority, he refer himself alone to the mercy of the Common God and Father of all men. NYS law nullifies slaver’s federal

execution?

On virtually the eve of the execution, in arguing for stay, Gordon’s attorney noted that the words of sentence specifically designated the City Prison, aka the Tombs, as the place of execution. Dean argued: The

[sentence] in this case . . .

directs the execution to take place within the City Prison. I wish to raise the question whether that

sentence can be carried into effect in this State without the consent of the

State. . . . Now, the [first] Section of the Act of 1860 of this State provides that no crime hereafter committed, except high treason and murder in the first degree, shall be punished with death in this State. . . I do claim that the first section applies distinctly to executions in any of the county jails in this State, and by that the Legislature has declared that they will not have their property applied to such purposes except in cases of treason and murder. . . .

The City Prison is private property to a certain extent.

It belongs to the City. I don't believe the [federal] Court can say that an

execution shall take place there any more than in the house of the District

Attorney. I am informed that the [New York City] Commissioners of

[Public] Charities and Corrections have given a consent that this execution

shall take place in the City Prison. If they have it, it is entirely nugatory.

They might as well give consent to turn it into a brothel. The consent must be

given by the State. Dept. consents to executionU.S. District Attorney E. Delafield Smith in reply, cited the statute of 1860 as giving the Commissioners of Charities and Corrections complete control over City Prison, among others. He read into the record a letter by the commissioners’ board president, Simeon Draper, addressed to the U.S. Marshal Robert Murray, consenting to the execution taking place at the Tombs. Dated Feb. 19, 1862, on letterhead of the Department of Public Charities and Correction, No. 1 Bond St., near Broadway, it stated, in part: In compliance with your request for permission to execute

Nathaniel Gordon in the [prison] yard . . .on the 21st inst, the

Correspondents grant the same, and the Wardens of City Prison will [make] the

usual [arrangements] required on such occasions.

Rejection of last-ditch appeal

Judge Shipman took a short recess during which he examined relevant case law and statutes as well as conferred with fellow Federal District Judge Samuel Rossiter Betts. About 6 p.m., the Judge returned into Court to render his decision rejecting the defense request for a stay of execution. Shipman stated: . . . I should say in disposing of the matter . . . that

the place of execution of the sentence of Gordon was the subject of

deliberation and consultation before the sentence was delivered. The City Prison was not hastily or

accidentally designated, but was fixed as the place after full consultation. .

. . The Court is of opinion that the prisoner was, at the

time of his trial, conviction and sentence, with the assent of the authorities

having charge of the City Prison, properly confined therein, and that was the

place designated by the Court for the execution of the sentence. We [see] no

occasion to interfere with the execution of the law in conformity with the

judgment and sentence. Attempt to cheat Tombs gallows

At the same time that the ruling was being handed down in Federal Court refusing to stay the execution, the 28-year-old condemned man’s young wife and aged mother were having a tearful last visit with him at the Tombs. Later that same evening, after being visited by Marshal Murray, Gordon wrote about a dozen letters, including one to his son to be opened when the boy would be old enough to read and understand it. The inmate smoked a few cigars before going to bed about 1:30 a.m. of his last day. About an hour and a half later, Keepers Finley and Rowe observed him having convulsions. The prison physician Dr. Simmons and two others in attendance, Drs. R. Wood and Hodgman, diagnosed the symptoms as consistent with strychnine poisoning. Since during the previous evening, the prisoner had been stripped, searched, given a fresh uniform and moved to a different cell, Tombs authorities theorized the strychnine must have been in the cigars and that he had administered it to himself to cheat the gallows. Indeed, as the doctors strove to save from the deadly poison the life that would be taken by the deadly rope before the day was done, Gordon had transient periods of consciousness during which he begged them to let him die so as to spare him the ignominy of being hanged. By using a stomach pump and administering liberal quantities of brandy, the physicians revived him sufficiently that the execution could take place. It had been planned for about 2:30 p.m. but, in view of Gordon’s precarious physical condition, Marshal Murray had the time moved up to noon despite pleas by the lead defense counsel not to do so. Dean told the marshal that New York’s Republican Governor Edwin D. Morgan had interceded for Gordon, telegraphing Lincoln for a reprieve. The lawyer argued that advancing the execution time would preempt the President acting favorably on the governor’s request. Some Tombs execution history

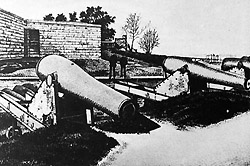

In Gordon’s Tombs death row cell, before his arms were pinioned, he asked for something to drink. He was offered and drank several glasses of brandy that seemed to revive him. The marshal, to whom the prisoner had given a lock of his hair for Mrs. Gordon afterwards, read aloud the words of the death sentence. The Rev. Mr. Camp, who regularly counseled Gordon spiritually, led the prisoner in prayer, at the end of which the convict expressed that hope that God would be merciful toward him. About 12:10 p.m., Public Charities and Correction Commissioner Draper announced that the time was at hand to proceed to the gallows in the Tombs prison yard. After some minutes spent arranging the correct order of procession, the cortege moved at 12:20 p.m. from the prison corridor to the yard. Marshal deputies supported Gordon on each side. Among those in the procession, besides City Prison officials and federal marshals, were Gordon trial jurors and members of the press, as was the custom in that era. The City Prison yard had been the scene of several executions since the Tombs began operations in 1838. Until the state superseded the counties in carrying out the death penalty, executions were usually held at the county correction facility that had housed the prisoner at the time of conviction and sentence. But beginning in 1890, the state took over executions, substituting the electric chair for the hangman’s noose. In the half-century that the Tombs prison yard was used for hangings, about 50 condemned convicts were dispatched there.

The first was Edward Coleman, a mat maker from the nearby rough-and-tumble Five Points section convicted of slitting his wife’s throat Saturday morning July 28, 1838. She had been panhandling near Jollie's Music Shop, Broadway and Walker Street when attacked. Coleman tossed away the razor later recovered, remained at the scene until arrested and was quoted as saying “I done it.” Anger over suspected infidelity was the reputed motive. He was executed in the Tombs yard Jan. 12, 1839. The particular gallows whose steps Gordon mounted, with marshals’ assistance, had long been in use at the Tombs. It was known to have been employed at least as far back as Jan. 28, 1853 in the execution of Nicholas Saul, 20, leader of the Daybreak Boys gang from the city’s 4th Ward, and his sidekick, William Howlett, 19. They had been convicted in the Aug. 25, 1852 murder of night watchman Charles Baker aboard the brig William Watson anchored in the East River between Olive St. and James Slip. He had come upon them looting the ship. More recent to the Gordon execution, the same scaffold had been used to carry out the sentence against James Stephens, 36, a factory worker. He was hanged Feb. 3, 1860, having been convicted of murder. The execution scene

Once positioned beneath the noose and before being hooded, Gordon could look out upon a thong of people. Marines, commanded by a Captain Cohen, stood at the ready, with rifles and fixed bayonets. Some were deployed around the scaffold itself; others, in lines that cleared pathways for the execution procession, and still others at the main entrance to the prison on Franklin St. where they assisted police -- commanded by a Capt. Downing of the 6th Precinct in keeping back the crowd of general spectators. A picket fence had been erected some distance away from the gallows, also to keep back the curious public. Some onlookers occupied vantage points on the roofs and in the windows of the upper stories of nearby buildings overlooking the prison yard.

Within the fenced-off area, members of the press were positioned directly in front of the scaffold. To the left were the attending physicians and jury members while to the right was the executioner’s box that concealed the weights, axe and the hangman. The Tombs was known for employing a type of gallows that jerked the condemned person upward upon the release of weights by application of an axe to a rope that, until then, held them in abeyance. That design, intended to produce near-instant death by breaking its victim’s neck, was believed more efficient and humane than dropping the noosed prisoner through a trap-floor opening beneath his feet, which method often resulted in agonizingly slow strangulation. Gordon spent his opportunity for last words in confusing complaint about the U.S. District Attorney reneging on an alleged promise of commutation, a claim running contrary to the court record and Smith’s known advocacy of imposing the death penalty to end slave trafficking. The actual hanging

Whether from post-poisoning weakness, or the brandy, or plain fear or a combination of those factors, the prisoner began to swoon. Quickly the black hood was placed over his head, he was steadied and the marshal signaled the executioner who applied the axe. Immediately Gordon was jerked upward into the air by the noosed rope.

Aside from a few twitches of the hands briefly, there was no sign of struggle in the body, no heaving, no contortions. After 15 minutes, the body was lowered for examination by attending doctors, including Dr. George F. Shrady who was then just starting out on his long and distinguished medical career. They announced the body had no heartbeat or wrist pulse. However, the authorities decided to let the body dangle a few minutes more just to make certain. At about 12:45 p.m. the execution was declared concluded. The body was taken to another part of the Tombs complex where an autopsy determined Gordon’s neck and thyroid cartilage had been broken, indicating death had been almost instantaneous. Why the Tombs for a U.S. execution?

So the federal death sentence -- under a piracy law expanded four decades earlier to include slave trafficking -- was carried out at City Prison despite the defense challenge to the Tombs as the site. But why had the Tombs been so deliberately selected and particularly specified in the sentence as the place of execution for the convicted slave trafficker? Fewer than 18 months before the Gordon sentence was handed down by Judge Shipman in late 1861, another prisoner at the Tombs – deemed a pirate and convicted under federal law – was taken from the City Prison to be hanged on the island that in 1877 was designated to become home to the Statue of Liberty. The authorities were believed to have moved the “pirate/murderer” to that location for the execution because it was federal property and he had been convicted under federal law. That condemned man was Albert E. Hicks, convicted in a triple murder committed aboard an oyster sloop at sea. The captain and two mates had been axed and valuables taken. His execution on July 13, 1860, has passed into New York City lore, complete with its own folk song retelling the festive mood among the 1,500 who booked passage on the steamboat Red Jacket to witness the hanging on Bedloe’s Island. The boat also carried, under guard, Hicks whose mood must have less festive. The island then was chiefly occupied by Fort Wood, whose construction as part of a battery defense for New York Harbor was completed in 1811. More than a decade and a half following the pirate/murderer’s execution in 1860, the old fort’s thick walls, that formed a distinctive 11-pointed star, became the base for the Statue of Liberty. The Hicks execution at nearby Fort Wood 17 months before the Gordon’s sentence serves to underscore the question: Why was City Prison selected for Gordon? Whereas Gordon’s lawyer argued the execution site selection was an illegal contravention of New York State law, the question posed in this correction history presentation is: Why was the Tombs selected rather than Fort Wood or any one of several nearby federal military installations?

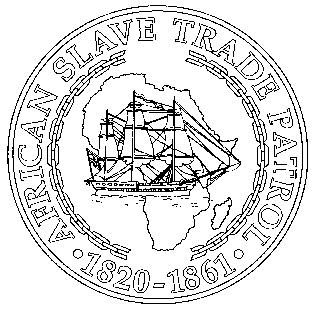

Slave trade background

To form a possible answer, consider some public policy and political factors. Several New York City businessmen in the 1850s frequently invested in slave smuggling operations and realized profits in the $150,000 range per voyage. Importation of slaves, despite federal prohibitions against it, beginning in 1807, continued in such volume that the total number of such “illegal slaves” smuggled into the U.S. by 1860 during the preceding half-century is estimated to have been more than 1.2 million. For the South to expand slavery into the new Territories and the emerging new states, illegal importation of slaves would have to continue. Slave trafficking had increased as various federal administrations signaled prosecutions under slave trade piracy laws would be less than vigorous. But the ninth plank of the new Republican Party's 1860 national

platform vowed to end it: We brand the recent re-opening of the African

slave trade, under the cover of our national flag, aided by perversions of

judicial power, as a crime against humanity, and a burning shame to our country

and age, and we call upon congress to take prompt and efficient measures for

the total and final suppression of that execrable traffic.

Execution part of war on slave trade

U.S. District Attorney E. Delafield Smith, as Lincoln’s appointee, took over the prosecutor’s office in April of 1861 with a firm intent to enforce anti-slave trade laws to the fullest extent. A Nov. 19, 1862, letter by him to Lincoln's Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, who had been a lawyer for the slave Dred Scott, makes clear that Smith saw the Gordon sentence as a key part of a three-prong strategy. Three things are required to end the slave trade at this

port[New York]: First, To stop the

fitting out; Secondly, To restrain American officers and seamen from serving on

slave ships; and Thirdly, To extirpate "Straw Bail" for vessels

seized for the offence and then bonded or bailed and discharged. Smith’s letter cites three prosecutions brought by him as

serving that strategy: The first will be accomplished in the conviction of

the merchant, Albert Horn; the second,

by the execution of Gordon; and the third, by the punishment of Blumenburg.

Albert Horn was a New York merchant sentenced to five years in prison for fitting out the City of Norfolk, a slave trade ship. A ships bondsman named Blumenburg appears to have also been convicted of involvement in the slave trade but was trying to use his Republican credentials to evade punishment. Efforts also were being made to gain a pardon for Horn. Smith commented: The exertions now on foot to relieve Horn, will render his pardon necessary, if Blumenburg be released. And the discharge of them or either of them would make the execution of Gordon an idle and therefore a cruel ceremony. Smith opposed Horn and Blumenburg winning discharge. To him, their punishment preserved the purpose of Gordon’s execution because all three cases were part of an integral anti-slave trade package. In Smith’s view, Gordon’s hanging was a purposeful event, a public ceremony with validity and meaning. But pardons for Horn and Blumenburg could render it an idle and therefore a cruel ceremony. Assuming therefore, as seems warranted, that the first execution of a American slave trader was intended to warn mariners that they literally risked their necks if they engaged in such activity, what execution site would best serve having that message broadcast most widely and fully? Some remote island military fort generally off limits to the public and press in the midst of the Civil War or the most notorious prison in the city that was already on its way to becoming the media capital of the world? The question answers itself.

Although, thanks to Smith's perseverance, Horn and Blumenburg both apparently served some time behind bars, the former did gain a commutation on May 20, 1863. However, by that point, Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation and other Civil War developments had made clear that the slave trade's demise, if it ever was to happen, would come to pass, not in courts nor prisons nor on gallows but upon bloodied battlefields. Either the Union would survive or slavery would, but both could not. The president's Nov.19, 1863, Gettysburg Address forever framed the larger issue emerging from what had begun as a War Between the States. To him it had since become "a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation" so conceived in Liberty and so dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, can long endure. What Lincoln prophetically proclaimed then still rings with relevancy 140 years later: It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated . . . to the unfinished work . . . It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us --. . . that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain -- that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom. . . In counting those for whom we the living are to remain highly resolved that they shall not have died in vain, ought we not also to include, in addition to usual count of 620,000 Civil War dead, the 30 West African slaves who died aboard Gordon's ship, the Erie? And the millions more who similarly died on other slave trade ships of the Middle Passage? And the countless number more who died from the cruelties of slavery's yoke on land? A reading of Lincoln's March, 1865 Second Inaugural Address would suggest that he at least would have probably included them in the count: Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether." | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright

by Thomas C. McCarthy and the New York Correction History Society as to text aside from indicated quotations. New York. 2003.Non-commerical use permitted provided the society and/o web site are duely acknowledged as the source.