The New York Police Department's first Black officer, the New York City Correction Department's first female commissioner and its first Black commissioner share with the New York Yankees' legendary "Iron Man" first baseman historical linkages to America's first municipal parole board: the New York City Parole Commission that functioned from 1915 to 1967.

Samuel Jesse Battle became the first African American appointed to the NYPD uniformed force on June 28, 1911, as a result of his successfully overcoming the department's initial rejection.

Having passed the written exam in 1910, Battle -- then a ranking red cap at Grand Central Station -- was denied appointment when a police doctor diagnosed he had a heart condition. The Harlemite -- 6 foot 3 inches tall and weighing 280 pounds -- refused to accept the finding and appealed to the Civil Service Commission. Its medical team pronounced him fit. So the Department had to appoint him but accepting him as a "brother officer" was another matter altogether.

How Battle's quiet perseverance and bravery, including rescuing a threatened white officer, overcame initial hostility of many on the force and how he rose through the ranks by dint of study, hard work and a spotless record is one of those inspiring "New York firsts" stories worthy of repeated retelling but, in fact, is rarely told.

Not very long after Patrolman Battle was assigned to Manhattan's West 135th Street Station in 1913, a new administration came to power at City Hall and initiated a series of progressive reforms of the municipal jail and prison system. One of those reforms would figure significantly in the last decade of what would prove to be Battle's 40-year city service career.

John Purroy Mitchel surprised most people, even supporters of his successful 1913 campaign as the Fusion-Progressive Party candidate for mayor, when he picked Bedford Hills Reformatory Superintendent Katharine Bement Davis as his Correction Commissioner. Upon her appointment Jan. 1, 1914, she became not only the Department of Correction's first female commissioner but also the first woman to head any major municipal agency in the city's history.

Dr. Davis -- Katharine held a Ph.D. in political economics from the University of Chicago, the first earned by a woman -- was in charge of 5,500 inmates -- mostly males -- in nine city prisons and jails operated by 650 uniformed and civilian employees -- mostly males -- with a $2 million annual budget. Thus she had become quite possibly the country's highest ranking female municipal agency executive in terms of department size, status and powers. Her "elevation" to that position was a breathtaking development in the midst of the women's suffrage struggle then taking place. She put her high visibility at the service of that cause by becoming one of its leading spokeswomen. [More on that aspect of her life can be found elsewhere on this site in the biography Correction's Katharine Bement Davis: New York City's Suffragist Commissioner.]

Among the many reforms that Commissioner Davis initiated was the creation of the New York City Patrol Commission in December, 1915, becoming its first chairperson. Indeterminate sentencing, with possible parole as an incentive for inmate efforts at rehabilitation, had been a principle of progressive penology for decades. The innovation Katharine championed was the principle's application on the municipal level. That no other city in the nation had such panel did not deter Davis. In fact, she viewed that as an opportunity for New York City to show national leadership.

The 1915 law ended the definite term aspect of city penitentiary and workhouse sentences, and eliminated the payment of fines as an alternative to incarceration. It substituted sentences for an indeterminate period not to exceed three years for all penitentiary inmates and an indeterminate period not to exceed two years for workhouse frequent repeaters.

As set up by Davis, the city parole panel consisted of five commissioners including the Police and Correction Commissioners serving ex-officio. The other three panel members were appointed by the mayor specifically to serve as Parole Commissioners.

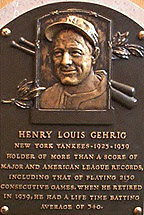

On Oct. 11, 1939 at the World's Fair "City Hall" in what is now Flushing Meadow Corona Park, Queens, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia announced the appointment of Henry Louis Gehrig as a member of the Parole Commission for a 10-year term to begin the following January. Little more than two months earlier, the original "Iron Man" of baseball had stood before a microphone at Yankee Stadium home plate and uttered to the hushed fans filling every seat and every standing-room-only space his farewell to the game he loved and that loved him back:

The colorful and daring Babe Ruth had infused the game with his zest, verve and excitement but reliable and decent Lou Gehrig had ennobled it with his own natural dignity, grace and character. LaGuardia acknowledged this aspect of his appointee by explaining:

The unspoken issue was how much life could be expected for him, never how much devotion could be expected of him. As usual, he gave it his all. Lou applied himself to his new career with the same perseverance and determination that he had applied to his former one.

Once officially a Parole Commissioner, he immediately scheduled visits to the city's correctional facilities, starting with the Tombs and Rikers, but insisted they be treated as work-related without news media, not as press events. To avoid any appearance of grandstanding, he had his listing on the agency's letterhead, directory displays, and publications read "Henry L. Gehrig" (as in the letterhead from the Municipal Reference Library at the top of this page). Up until about a month before his death Gehrig went regularly to his Parole Commission office at 130 Centre St. He stopped on doctors' orders after he was hardly able to walk any more. Two weeks later he was completely confined to bed where, another two weeks later, the disease that had been little known until he was diagnosed with it took his life and he gave it his name. More than 60 years have passed since that rare day in June, 1941 when every front page in America proclaimed the same story: that the great and gentle Gehrig, the Pride of the Yankees, the Iron Man, the player of 2,130 consecutive games, had been scratched from the lineup card of life by a crippler with an appropriately cumbersome name: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. By making it better known as Lou Gehrig's Disease, he has -- if not overcome it -- risen above it and made his courage in the face of it, including his performing his Parole Commissioner duties to the virtually very end, an example for others with ALS.

On June 20, 1941, Samuel Jesse Battle, by then a Lieutenant in the NYPD's Sixth Division in Harlem, was named by Mayor LaGuardia to fill the remainder of Gehrig's unexpired term running to January, 1950. The city's first Black patrolman had become its first Black police sergeant on May 21, 1926, and its first Black police lieutenant on Jan. 7, 1935. After his retirement from city service in 1951, Battle continued to serve the Harlem community through YMCA, NAACP and Urban League programs, especially those to help young people. He died Aug. 6, 1966. In 1946 -- about the time Battle was into his fifth year as Parole Commissioner -- a young man joined that agency as a Parole Officer, thereby starting out on what would become a long and distinguished career in the correctional field. His name: Benjamin Malcolm. A native of Philadelphia (May 25, 1919), a graduate of Morehouse College in Atlanta, and a World War II veteran, he started as a NYC Parole Commission officer and advanced through the ranks during the ten years that followed. But then the applicable law was rewritten to set the maximum sentence an inmate could serve in a city jail at one year and to have any longer sentences served in prisons run by the New York State Department of Correctional Services. The revision of the law, effective in 1967, extended the State Parole Board's release authority to persons incarcerated in local reformatories, transferring the functions of the New York City Parole Commission to the New York State Division of Parole. In 1970, Benjamin Malcolm received his master's degree in public administration from New York University. On Dec. 14 that same year, Mayor Lindsay appointed him Deputy Commissioner to Correction Commissioner George McGrath. On Jan. 24, 1972, the Mayor named Malcolm as Commissioner. He thus became the first African-American to head the municipal jail agency. He served until Nov. 19, 1977, when he stepped down to accept appointment by President Jimmy Carter to the U.S. Parole Commission. In 1984, when Malcolm's term as a U.S. Parole Commissioner expired, New York Governor Mario Cuomo offered him chairmanship of the State Parole Board but he declined, deciding instead to launch a private research company, Parole Services of America, to provide inmates seeking parole with relevant comparative parole data. In that role, he often traveled around the country, but made his home on Roosevelt Island that in past eras had been called Blackwell's Island and served as the main base of the city's correctional system. Occasionally the former Commissioner would visit DOC headquarters at 60 Hudson St., in the Tribeca section of Lower Manhattan. Learning of the emergence of the New York Correction History Society, he expressed keen interest, noting he had played a part in making some correction history. On May 25, 2001, Benjamin Joseph Malcolm passed on into that history, joining there others who also played their parts helping make some of it, including his fellow former New York City Parole Commissioners Katharine Bement Davis, Henry Lewis Gehrig and Samuel Jesse Battle. Today, their names are etched firmly in the list of New York "firsts" -- the first female commissioner and the first Black commissioner of NYC Correction, the first Black NYPD officer and the first Iron Man of baseball. But faded from New York City collective memory is awareness that another "first" figured significantly in the lives of these four history-makers -- the New York City Parole Commission, the first of its kind in America. The Webmaster, New York Correction History Society |