Mission News January 1906:

Mr. Thomas McCandless has been elected a member of the staff (of the New

York Protestant Episcopal City Mission Society), and assigned to duty on Hart’s Island,

where he is doing a splendid work among the boys in the new Reformatory established

there.

|

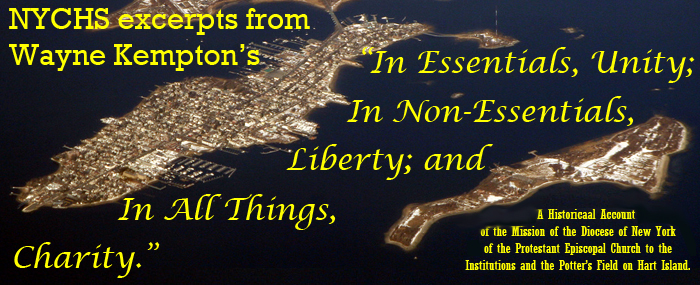

| Graphic pen sketch of Hart Island Branch Workhouse & Women's Pavilion as seen in a Harvard Art Museums on-line circa 1900 photo. The above image & caption do not appear in the original work. |

Mission News February 1906:

THE MISSION ON HART’S ISLAND

Seventeen miles by water from East 26th Street, well out in Long Island Sound, lies

that “ultima thule “of New York’s penal system — Hart’s Island. On this little-known and

rarely-visited islet are located the Branch Workhouse, and the Boys’ Reformatory.

The

Workhouse, in its scattered wooden buildings, houses approximately 500 men and 25

women. The Reformatory is overcrowded with nearly two hundred boys. Not one New

Yorker in ten thousand, perhaps, has ever heard of this place, and yet Hart’s Island has a

peculiar interest, for here one may see boys, who have only begun a life that perhaps shall

be largely spent within prison walls, and also ancient pensioners at the scant table of a

city’s charity — old men who look from the windows of the only home they know, upon

their last long resting place — the Potter’s field.

The boys are housed, in a separate building, on the dormitory plan; which means

simply that two hundred boys can be and are packed into a building that should properly

shelter not many more than one hundred. With no privacy possible, each boy must carry

with him, wherever he goes, his entire possessions.

|

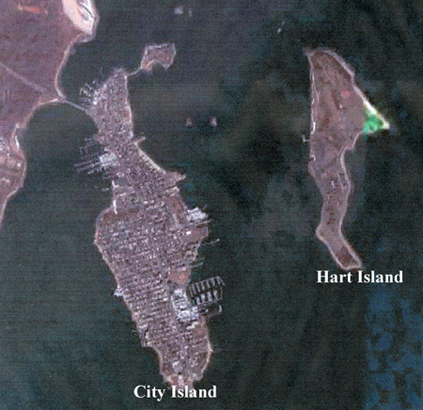

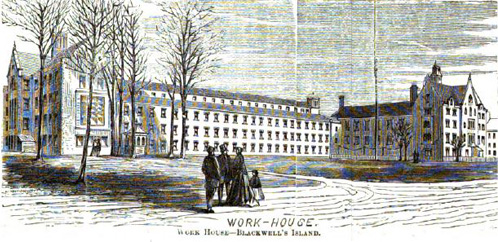

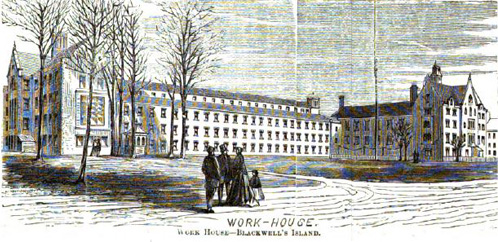

| The Workhouse on Blackwell's Island (now Roosevelt Island) for which the Workhouse on Hart Island was "the Branch." Illustration is from Rev. John Francis Richmond's New York and Its Institutions: 1607 -- 1872.The webmaster has added the above image & caption to this presentation. |

So when our Sunday School class

comes in, each boy wearing a heavy Turkish towel around his neck, in a hot and badly

ventilated room, we recognize this strange garb as only a practical way of keeping one’s

property.

“Dormitory” has a prettier sound than “cell,” but the quiet chance for reading or

study would be a boon to most of them — a boon that the dormitory system denies.

To a worker in this field, the task appears at once hopeful and hopeless — hopeless,

when one considers these aged or crippled, bodily or mentally unsound, inmates of the

Workhouse; hopeful, when one looks into the faces of these boys. The men have long

since been cast aside, useless and perhaps dangerous derelicts on the sea of life. The boys

have life’s great journey still before them. Very few of them are deliberately criminal; the

majorities are here because of bad companions or parents worse than none.

Under a law lately put into effect, a new class of boys, known as “misdemeanants,” is

being sent to Hart’s Island. They are committed for a term of three years, but this may be

commuted for good behavior, to a minimum of three months. These newcomers are being

taught to work at making hosiery and shoes for the various penal institutions; and

ultimately, it is thought; most of the boys sent here will belong to this class. Under a

trained and efficient instructor, school sessions are held morning and afternoon; regular

attendance is compulsory.

|

| Some of the illustrations added by the webmaster to this presentation come from the Rev. John Francis Richmond's New York and Its Institutions: 1607 -- 1872. Its title page image appears above. Rev. Richmond's five years engaged in "city missionary" work during the late 19th century brought him into contact with the institutions about which he wrote.

The webmaster has added the above image & caption to this presentation. |

On Sunday mornings, we gather the boys for an hour of Bible study. They are quiet

and studious, giving far less trouble than many a city class. At half past one, we have

afternoon service; and it is an interesting sight to see the long line of men, the lame, the

halt and the blind, come slowly into the chapel. Then comes a division of the able-bodied

men, and lastly the boys. All join heartily in the service; the hymn, if at all familiar, is

sung with a splendid and uplifting zeal.

As this is the least known, so it is also the neediest of the city’s institutions. The boys

and men ask for reading matter with an eagerness that is pathetic. We receive, and

distribute weekly, about two barrels of magazines and periodicals, which are furnished us

by the Church Periodical Club. Among so many elderly men, there is a great demand for

tobacco. And if this should reach the eyes of some smoker, who has plenty of this world’s

goods, let him bestow a little private charity. Five dollars a month would mean more

happiness here than ten times as much could purchase outside.

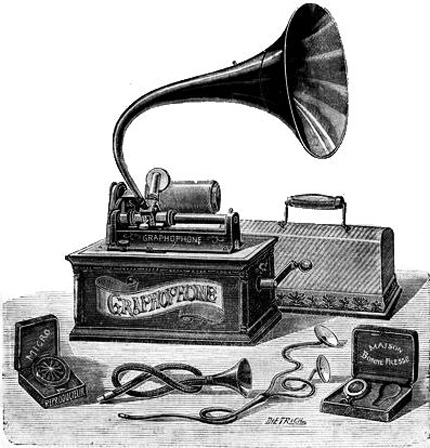

The Chaplain is very anxious to secure the amount needed to hire a larger-sized

gramophone, with twenty or thirty records, to give the prisoners now and then an

afternoon’s entertainment, which they would greatly appreciate.

“A very needy field,” you will say. And it is. But it is a blessed privilege to work in

such a field, to bear light into so dark a place, and to feel that, through God’s mercy, even

the walls of a prison may ring with songs of praise and thanksgiving for the souls of men

redeemed.

Mission News March 1906:

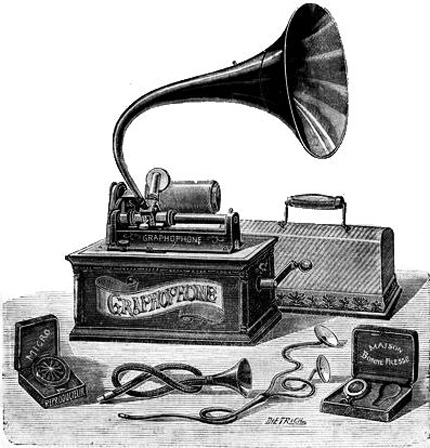

THANKS! –The prompt response to the request for funds to get a graphophone

for Hart’s Island, deserves a prompt expression of thanks. We are in a fair way to own an

instrument, and have given an entertainment by this means. 750 men and women, boys

and babies –which means every soul on the Island who could crowd into the Hall –

enjoyed an hour of good music well played. We have hopes also in the way of tobacco.

Mission News April 1906:

|

| The Rev. Mr. Thomas McCandless, in his 1906 Mission News reports on his Hart Island activities, used the terms "gramophone" and "graphophone" in reference to playing recorded music for the entertainment of inmates. He may have been using them loosely; that is, interchangeably. Or he may been quite precise, starting off with a gramophone machine playing flat records such the above but then acquiring a graphophone that played cylinders as the one below. In that early era of recorded music playback, the two technologies -- cylindrical vs. flat -- competed.

The images above & below & their caption do not appear in the original work. |

|

MORE ABOUT HART’S ISLAND

. . . . We rejoice in the possession of a first-rate graphophone; that means a weekly

treat to every soul on the Island. The Church Periodical Club is our mainstay for reading

matter of all sorts. Several persons have answered our appeal for tobacco and for

magazines. We have received a piano and a communion service. Altogether, our “cup

runneth over,” and Hart’s Island seems every day less forlorn, less forsaken of the people

of God. Surely THE MISSION NEWS may boast of generous, as well as “gentle,”

readers.

It is a pleasant duty also to express our appreciation of the unfailing courtesy and

helpful kindness of Warden [Thomas F.] Kane. Himself a Roman Catholic, he has in every possible

way aided and encouraged the work we try to do. . . .

The work among the boys is, of course, by far the most interesting and hopeful. These

are no depraved and desperate criminals, defiant toward God and dangerous toward man.

They are simply boys who, born into families too poor and too ignorant to constitute a

home, have never been given a fair chance in life. Many of them are here for no crime but

poverty and homelessness. Now and then we find among them an ambitious boy who

came to the city to make his fortune, and was picked up as a vagrant. Of course, there is a

small percentage of out-and-out scoundrels among them . . . .

To them all New York City owes a home and training far different from what she so

grudgingly gives. Our great, rich city abuses a good word when she speaks of her

“Reformatory.” These boys should be taught useful trades, taught the proper care of their

own bodies and minds, made to realize that there is for each one a useful and honorable

place among men, and not be turned out at the end of their stay on the Island as ill equipped

for life’s battle as when they came here.

To be sure, the city has made one step forward in their treatment. The new class of

boys, called “misdemeanants,” is required to work at the making of shoes and hosiery,

and a small class of them is being taught telegraphy. But simply to supply power to a

machine that makes a stocking, or to cut endless pieces of leather by a set pattern, will

never train a boy for useful toil outside prison walls.

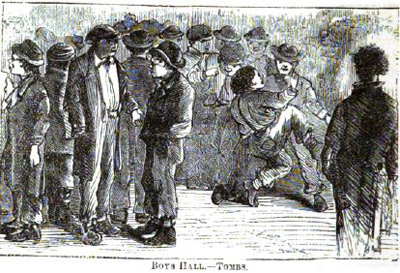

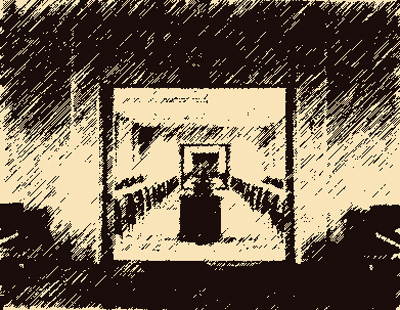

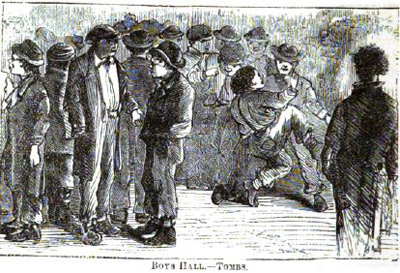

|

| The Hart Island reformatory represented an attempt to salvage youths who otherwise might be consigned to Boys Hall at the Tombs, depicted above in an illustration from the Rev. John Francis Richmond's New York and Its Institutions: 1607 -- 1872. The Tombs youth section was consider by some critics a School for Crime, with little to occupy its inmates besides toughs teaching the uninitiated lawlessness.The webmaster has added the above image & caption to this presentation. |

The ranks of labor are already

crowded with those who can do nothing but supply the infinitesimal factor of intelligence

needed in the running of most machinery. The boys should be taught plumbing, bricklaying,

painting and such other trades as could be utilized in improving and beautifying

the buildings on the Island.

. . . . Many of them are so

terribly homesick! They write woeful little notes beseeching those at home to write them

and to visit them. Some of their appeals would well-nigh break your heart, especially if

you knew they would probably go unanswered, or result in a visit from parents quite unfit

to see even their own child.. . . .

Less hopeful, but more exacting than the boys, are the men in the Workhouse; who

are here for a variety of causes — drunkenness, pauperism, homeless vagrancy, and “wife

cases ”— the poor’s substitute for the divorce court. In a separate building are the women,

about thirty of them, mostly victims of drink.

In the annex are gathered eighty or more

unfortunates, largely elderly men, not a dozen of them in full possession of their senses.

These men are absolutely out of place here. They should be in an asylum for the imbecile.

They need nurses, not keepers. It is from them we hear always the pitiable request for

tobacco.

Fit for no employment, hardly ever allowed to leave their secluded quarters,

their days and nights are embittered by their ceaseless craving for this, the only solace

they can enjoy. Once a week the city lavishes upon each of them half-an-ounce of

tobacco - enough for an hour or two. Then they begin to wait till the next week’s

allowance is doled out. But, thanks to the readers of THE MISSION NEWS, we have

been able to add a little to their comfort in this way. It will doubtless please you to learn

that your beneficence has materially decreased the consumption of their blankets, so

often used in lieu of tobacco.

|

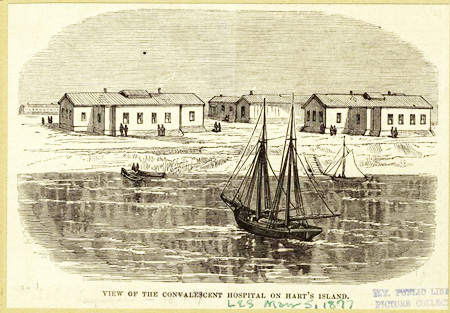

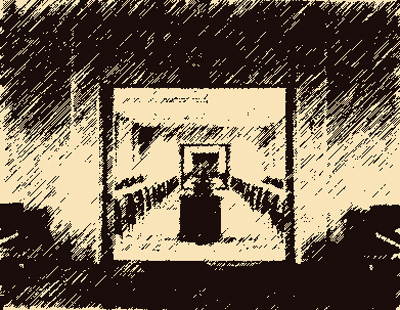

The above image DOES appear in the original work with this caption:"The Chapel at Hart’s Island

An Old Hospital Building a portion of which we are allowed to use as a Chapel. It is base, cold and

uninviting." |

. . . we are pitifully equipped for the work

to be done. We summon these poor, wayward children of God to worship Him in His

house, and lo! They gather in a place shamefully unworthy. Their very great needs, and

our very great responsibility for them, alike demand a fitting church home. Are there not

somewhere in this rich city, in the stewardship of some faithful servant of God, five

thousand consecrated dollars wherewith to erect on Hart’s Island a proper place for the

worship of Him who “came to seek and to save even that which was lost”?

The 1905-1906 annual reports of the Rev. Thomas McCandless follow:

* The Branch Workhouse, Hart’s Island 1905-1906

. . . Here, too, are the Branch Workhouse and the New York City Reformatory, or

School for Misdemeanants. The former, in winter, shelters as many as 650 inmates. The

latter contains on an average over 150 boys. In a separate building are about twenty-five

women prisoners, enough to care for the laundry and other necessary women’s work for

the island.

To the Branch Workhouse the inmates are committed for a variety of offences—

desertion and non-support, drunkenness and disorderly conduct, but most commonly for

vagrancy. The last named, like charity, covers a multitude of sins.

For instance,

imbecility — the sole offence of many — will bring us a homeless idiot to atone for his

crime by six long months of confinement. The old soldier who comes with his pension

money in his pocket to see the great city, and who is knocked senseless and robbed by the

kind stranger who offers him a drink, may stand next morning, speechless and dazed, but

guilty and a vagrant in the eyes of justice. The orphan country boy who makes his way by

stolen train rides to the city of his dreams may be rudely awakened, if caught in the

freight yards, by a six months’ sentence for his crime of vagrancy. Bowery “rounder” and

homeless boy, drunkard and petty thief, may all be branded with this convenient legal

label and are all treated alike by the impartial arm of the law.

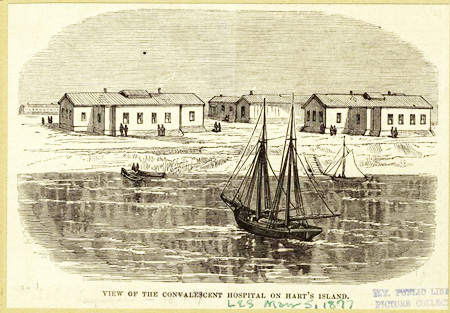

|

| The old hospital building which Rev. McCandless identified in 1906 as the structure where he was permitted to use part for Sunday worship services looks somewhat similar to the structures identified in this 1877 illustration as the Convalescent Hospital on Hart's Island."The webmaster has added the above image & caption to this presentation. |

But, to realize how far apart law and justice are, come and look upon the motley

company that crowds the Annex. These mental and physical cripples, blind and lame, old

and sick, are but poor game for the huntsmen of the law. These men, who cannot care

even for their own persons, are patients, not prisoners; they need nurses, not keepers;

medicine, not law.

Or come to the Island Hospital and see worn-out unfortunates dying the slow

death of senility, mumbling old men awaiting the boon of mortal sleep. They lay here,

perhaps fifteen or twenty, cared for by the faithful physician who does his best,

handicapped by insufficient help and prison diet. No fruit or flowers are ever sent to these

uncomforted sick; seldom does a visitor seek this lonely room.

* The New York City Reformatory 1905-1906

On the first of January, 1905, a law went into effect by which boys and young

men, between the ages of sixteen and thirty years, for such offences as petty larceny,

were to be committed to the New York City Reformatory or School for Misdemeanants,

on Hart’s Island. But not till December of that year were any boys committed under the

new law. Hence the latter date marks the first well-meant, but ill-equipped, attempt of

this great city to care for a rapidly growing section of her criminal population. . . . .

The system of merit marks differentiates this institution from similar reform

schools elsewhere. By this plan, for good behavior the maximum term of three years may

be commuted to a minimum of three months. Yet to anyone aware of what radical

changes must be effected in these young men and boys before they can be called

measurably, not to say permanently, reformed, it must be apparent that such a minimum

term is all too short.

|

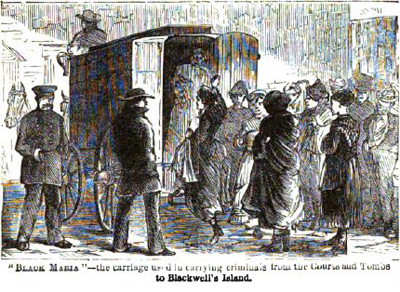

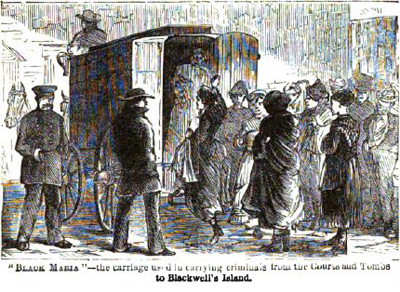

| A sketch of a horses-drawn police van, aka the Black Maria, pronounced “mah-RYE-ah,” loading prisoners for transport, was among the illustrations in the Rev. John Francis Richmond's New York and Its Institutions: 1607 -- 1872.The webmaster has added the above image & caption to this presentation. |

. . . . Yet there is great hope for the plan; the honest

desires of the officials to further the best interests of the boys are a guarantee that its

ultimate success is certain.

Thus far, about 350 boys have been sent to the school. Of these, over 200 have

been paroled, most of them after serving only the minimum term. There is now an

average of over 150 boys, never over 20 per cent of them Protestants. The “various

trades” they are taught, according to the hopeful prospectus, comprise at present the

rudiments of painting and shoemaking.

A plant for the making of hollow cement blocks

is soon to be started, which will serve the double purpose of teaching the boys a

profitable trade and furnishing material for much-needed buildings. Every boy, not a

graduate of the public schools, is required to attend school for one session daily.

Beyond this meager curriculum, its equipment does not, at present, permit the

work to advance.

Such obvious reformatory training as the teaching of personal neatness

and decent table manners is made impossible by overcrowding in an ill-adapted

dormitory. The same cause prevents the boys from spending their evenings in any manner

more uplifting than waiting for bedtime. Yet these defects will work their own cure. . . . .

It has seemed best to go somewhat into detail in our description of the institutions

on this Island, because it is a little known and practically new field for the work of the

City Mission, and because to describe such a field defines very clearly the work most

needed. And this precisely has been our aim: to know the inmates and their needs as

intimately as possible and to befriend them in whatever manner suggests itself as most for

their good. . . .

|

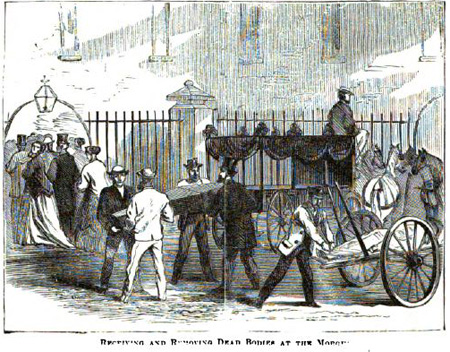

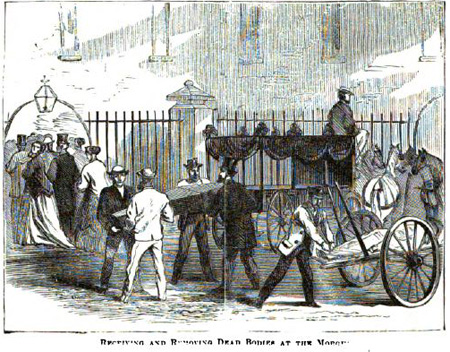

| Another illustration in the Rev. John Francis Richmond's New York and Its Institutions: 1607 -- 1872. depicts "Receiving and Removing Dead Bodies at the Morgue."The webmaster has added the above image & caption to this presentation. |

It is our

pleasant duty to acknowledge the continual kindness of the Church Periodical Club in

sending us weekly gifts of papers and magazines. . . .

Another source of much-needed aid is the Chrystie Street Home for Boys, and its

head, Mr.[Wallace] Gilpatrick. Many a boy of ours has he sheltered and clothed and set to work.

But for him many a boy would still be waiting for release from the Reformatory.

Nor can we ever forget in our thanksgiving the great number of anonymous

friends who have enabled us to supply regularly the poor old men with tobacco. . . .

. . . . Now and then a man is

found in prison that has a place waiting for him outside. In such a case the judge will

usually grant a shortening of sentence. In this way, during the past year about a dozen

men have been helped to their freedom, and, so far, not one of them has been

recommitted.

On Sundays we have morning service at 10 A.M. and Sunday-school for the boys

at 1:30 P.M. Both services attract practically all the boys and men as well as the few

women who are Protestants. We are proud of our services, for our congregation is as

reverent as and far more cordial than the usual gathering of worshippers. The Rev. Mr. [Henry St. George]

Young, the former Chaplain, visits us on special occasions to celebrate Holy

Communion. . . .

|

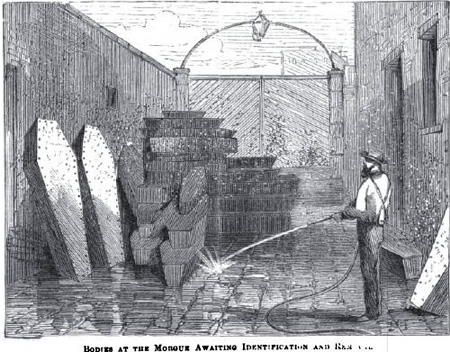

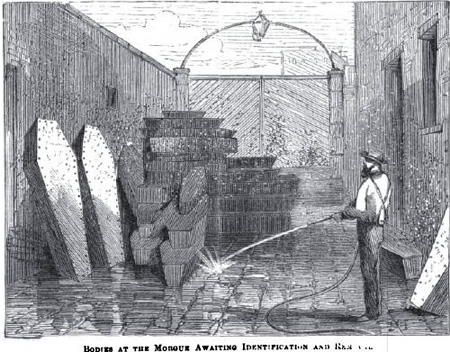

| An illustration in the Rev. John Francis Richmond's New York and Its Institutions: 1607 -- 1872, entitled "Bodies at Morgue Awaiting Identification and Rest . . .," depicts worker hosing an open-air storage area for coffins.The webmaster has added the above image & caption to this presentation. |

Our

organist, Mr. A. J. Gethen, deserves great praise for his patient skill in developing out of

chaos into inspiring harmony the musical part of our services.

Since last May we have regularly read the Burial Service over the bodies of those

unfortunates who are buried in Potter’s Field. The city can do little for these pitiful relics

of failure, except to give them a decent grave; the Church can and does consign them to

earth with the same stately service and the same high hope of a glorious resurrection as

she chants over the open graves of her own more fortunate dead. This vast and silent city,

numbering already over 142,000 dead, adds to its census the body of one in every ten of

those who die in all New York City.

. . . Our work is a very needy one; we have no fitting Church home;

we worship in an ugly and cheerless room; we gather the lame, the halt, the blind and the

diseased; but even here our hearts are warmed by the glow of the unseen Presence of Him

who came “to seek and to save that which was lost.”

From the 1905-1906 annual report of the Rev. Henry St. G. Young we read:

“On Hart’s Island I have officiated at two celebrations of the Holy Communion in the

Chapel and administered to four sick in the hospital, and at five other services in Chapel

and Sunday-school.”

|

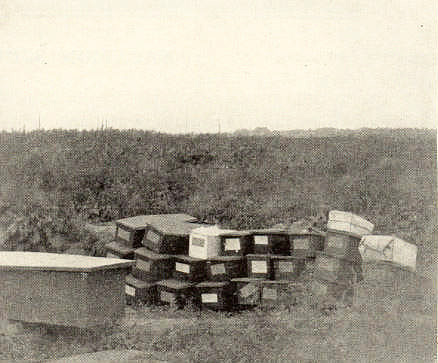

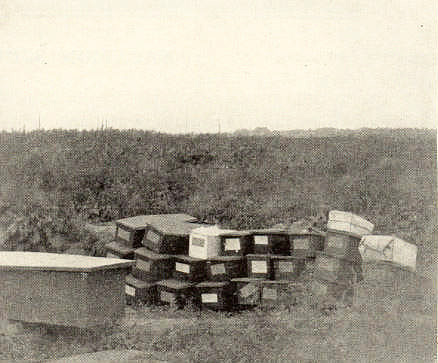

| The above image does appear in the original work with this caption: "The City Cemetery -- Hart’s Island -- Popularly known as the Potter’s Field." |

Mission News November 1906:

THE CHURCH AND THE POTTER’S FIELD

. . . . On wind-swept, sea-girt Hart’s Island, to the left of the millionaire’s yacht and the

humbler craft of popular pleasure or commerce that sail forth into the Sound, lie fifteen or

twenty desolate acres, the Potter’s Field. . . . here lie the bodies of over 142,000 persons, about three

quarters of them children. And here, we are told, every tenth person in this great city

finds his last long home. . . .

He is a man of no ordinary fortitude or indifference who can look dry-eyed upon

these bare, brown coffins, huddled by the gaping trench. Here are the tiny bodies of those

pitiable children who came to homes where poverty denied them a welcome. Others,

more fortunate, have never breathed the breath of life. So many of them lie here, little

wanderers whose life journey mercifully ended almost as soon as it began. . . .

The comprehensive purpose of the City Mission is to minister, in her varied fields, to

every spiritual need. The foundling at Bellevue is baptized into the Kingdom of God. The

people are shepherded throughout their lives; at death they are given the last Christian

rites.

|

| The above image does appear in the original work with this caption: “Here are tiny bodies of those pitiable children." |

As soon as the Society had secured a regular missionary for Hart’s Island, it was

possible to complete the circuit of our work and give Christian burial to the dead of

Potter’s Field. The officials of the Island gave their hearty consent, and offered every aid

in their power. The very prisoners who dig the graves were anxious that the service

should begin.

We wondered why so decent a thing had not been done always.

And so, since last May, the Service for the Burial of the Dead has been read each time

the bodies are brought from the morgue to Hart’s Island.

To the visitor it can hardly fail

to be a most impressive scene. The little group of prisoners, in their striped clothes,

gathers by the trench. They are quiet and reverential in bearing, standing with heads

bared of their own accord. No mourners weep for these lonely dead; no tribute of flowers

covers them.

But, over the open grave are spoken the stately words of our Burial Service

as the bodies are committed to the ground, “earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust;

looking for the general Resurrection in the last day, and the life of the world to come,

through our Lord Jesus Christ.”

|

| The above image does appear in the original work with this caption: “Huddled in the Gaping Trench.” |

Mission News December 1906:

“Can there any good thing come out of Nazareth?”was the contemptuous proverb

quoted by Nathanael long ago. “Can any good boy come from Hart’s Island?” might well

be asked today. Like Philip, we will answer, “Come and see.”

About a month ago, one of the boys on the Island came to me, asking if I could

find him a shelter in the city for a few days. Though in the regulation clothes, rough and

gray, of a prisoner, the boy’s clear, steady eyes were convincing. Here was a boy worth

while. When his time was up he was sent down to the Chrystie Street Home, where Mr. [Wallace]

Gilpatrick took him in, fitted him out with clothes and gave him a home. Less than a

week later he announced, in a triumphant postal, that he had found work as assistant

janitor in a public school— hours, 5 a.m. till 11 p.m., wages $20 a month.

Since then this boy has found work for two other boys who sorely needed it. Today

he is “hanging on,” as he calls it, looking for an easier job, where he can attend night

school. He’s a splendid fellow, with the makings in him of a noble man.

Is it not worth while?

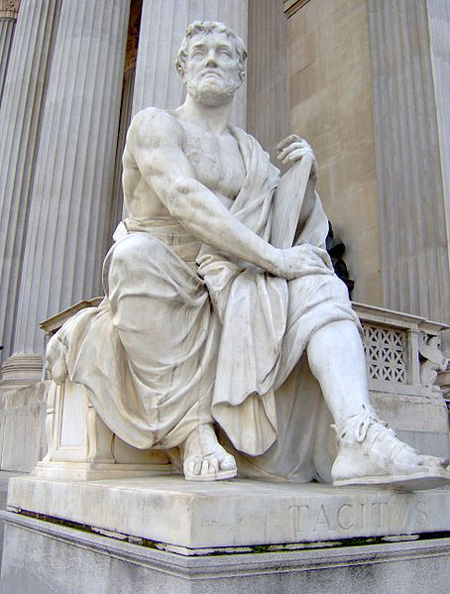

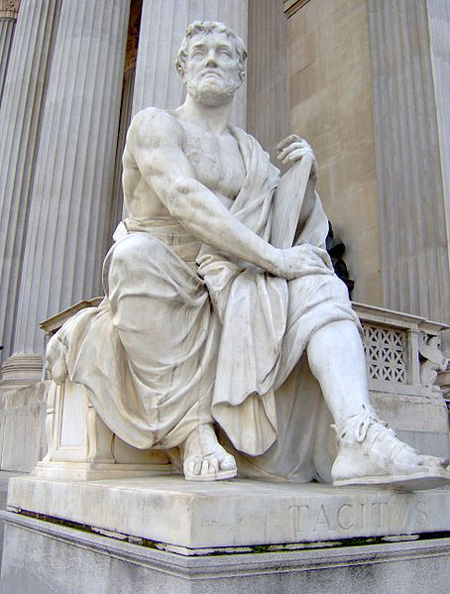

| Publius (or Gaius) Cornelius Tacitus, circa AD 56 – 117, quoted in the main text left, was a senator and a historian of the Roman Empire. A passage in one of his histories is one of the rare non-Christian ancient sources cited referencing Christ. Statue representing him sits outside the Austrian parliament building.The webmaster has added the image below & this caption to the presentation. |

|

Mission News March 1907:

THE BRANCH WORKHOUSE, HART’S ISLAND

Tacitus speaks somewhere of “Ultima Thule,” the “Ultimate Island,” and the

phrase recurs inevitably when dealing with that outpost of our city’s penal system, Hart’s

Island.

As for the dreary company of those who must owe their burial to our city’s

grudging charity, so to the pitiable throng here sheltered in the Branch Workhouse, this is

indeed the end of things, the last home of failure and despair.

On this bleak islet, as far

from the city’s sympathy as from the hum of her industry, are gathered the wretched

remnants swept aside from the human mechanism we call our city. Of this human rubbish

the economist would, no doubt, tell us that we are well rid; that within these worn-out

bodies may be hidden souls made in the image of God, is a matter, not of economic, but

of Christian, interest.

Today there are about six hundred and fifty men in this branch of the Workhouse,

by far the greater number of them old, helpless and homeless. With a few exceptions,

they are here because they know no better place to spend the winter, because they have

no other home.

By the end of March they will begin to be discharged, so that by the first

of July there will not be more than two hundred left. During the summer they will scatter

over the country, to return like homing pigeons, to the city with the first touch of frost.

Then, they know the combined interest of the policeman and the magistrate will secure

for them a warm and comfortable shelter till the snow flies once more.

|

| A still from a Hollywood retelling of O'Henry's The Cop and the Anthem depicts a vagrant (Charles Laughton) about to have his prayer answered as he hears a church anthem. The short story, published in the New York World in 1904 had as its milieu the seasonal migrations of those called the "old, helpless and homeless" in the Mission News March 1907 passages above.The webmaster has added the above image & caption to this presentation. |

But let not the anxious tax-payer fear that the city is wasting his substance in

maintaining open house for the country’s incapables.

This is no house of rest for the

weary; this is a place of punishment for crime. And so the inmates are not paupers, but

criminals.

They are clad in prison stripes, fed with prison food. It is a sad commentary on

a city’s wretchedness and poverty that for so many hundreds this mean and scanty diet is

an annual Godsend.

The able-bodied portion of the prisoners are housed in a separate building; to

them is entrusted the work of the island — digging the trenches in the Potter’s Field,

loading and unloading the boats, the laundry and the kitchen, etc.

In winter there is not

enough work to go round; in summer, not enough men for the necessary work. These are

a decent, well-behaved lot of men, whom it is a thousand pities to see in prison. They

represent just so much wasted time and energy.

A little magisterial consideration and

advice, a little “talking to,” after the manner of a Dutch uncle, would have settled the

domestic trouble that brought most of them here, and perhaps have saved a home.

|

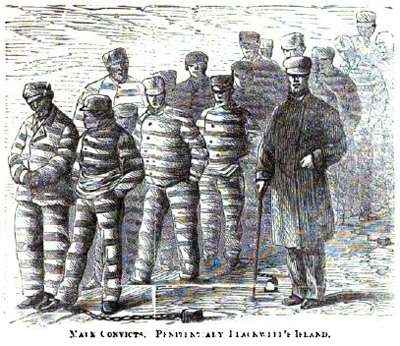

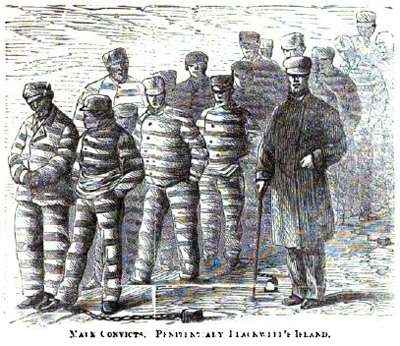

| An illustration in the Rev. John Francis Richmond's New York and Its Institutions: 1607 -- 1872, entitled "Yard Convicts, Penitentiary, Blackwell's Island" depicts zebra-chad inmates in the exercise yard under the watchful eyes of a keeper with his cane ready to rap out commands. Hart Island prisoners wore the same stripes and followed the same drill..The webmaster has added the above image & caption to this presentation. |

In the main building live the other four or five hundred inmates of the

Workhouse. And the pathetic thing about them is that with a few improvements in their

diet, and a very little more of the tobacco that is to them far more necessary than food,

they would be very fairly comfortable.

But, of course, the city does not wish, and cannot

afford, to care for the comfort of these unprofitable servants. She gives them enough to

eat, of a sort they can hardly eat at all; she gives them almost enough clothing to keep

them warm. But there are between sixty and seventy old men in the Annex who have not

yet had any socks this winter. The needless suffering this petty economy entails is a

disgrace to this big, rich city

If they become ill, they are sent to the Island Hospital, where a capable physician

battles bravely but vainly against the diseases rendered hopeless by vicious living and old

age. Again, the loving care of the city for her unfortunates is witnessed here; sick or well,

all have the same dietary. One sees toothless old men, trembling with weakness and age,

mumbling at their coarse and uninviting food. Poor things, so many of them are doomed

to die here, friendless and alone. They are grateful for the smallest kindness; their dim,

old eyes lighten with gratitude at the merest inquiry after their health.

|

| Graphic pen sketch of Hart Island Women's Pavilion interior as seen in a Harvard Art Museums on-line circa 1900 photo. The above image & caption do not appear in the original work. |

At the upper end of the island, live the women, usually about twenty-five of them.

They do the laundry work of the other inmates, and in manners and morals rank far lower

than the men.

. . . . here, among

the lowly and despised, you will find men and women who have traveled far on the road

to God. And as, among them, you will find every vice except dishonesty, so you will find

every virtue except economic efficiency.

As the fellow-prisoners of St. Paul could testify,

one may be in jail and yet be in very good company.

And the songs of Christian triumph

that, throughout the ages, have resounded from the prisoner and the captive, testify even

today that stone walls and iron bars can never exclude Him who came to seek and to save

that which was lost.

Mission News April 1907:

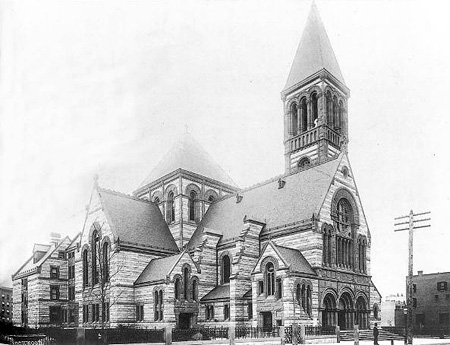

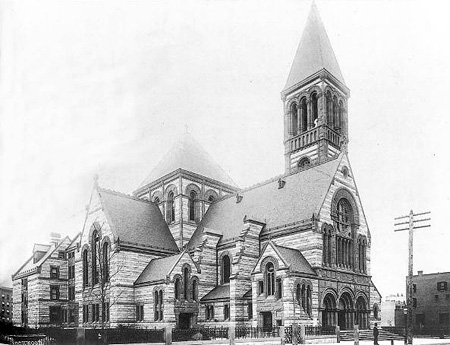

The Cross for the Potter’s Field

|

| The web site of the New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists includes the splendid photo above of Trinity Church's Chapel of St. Agnes, West 92nd Street, Manhattan. Built, 1892. Razed, 1943. SepiaTown also has an excellent image. In that chapel, the wife of Coadjutor Bishop David Hummell Greer launched the drive to erect the Hart Island cross.The above image & caption do not appear in the original work. |

An outcome of the public meeting of the City Mission Society held last January at St.

Agnes’ Chapel is a movement that has been started by Mrs. David H. Greer [nee Caroline A. Keith], to erect a

monument on the Potter’s Field that will mark in a fitting way the resting place of the

city’s dead and will stand as a symbol of Christian fellowship, showing that the people of

our city wish to keep these unfortunate ones in mind, and believe that they, too, belong to

the Master.

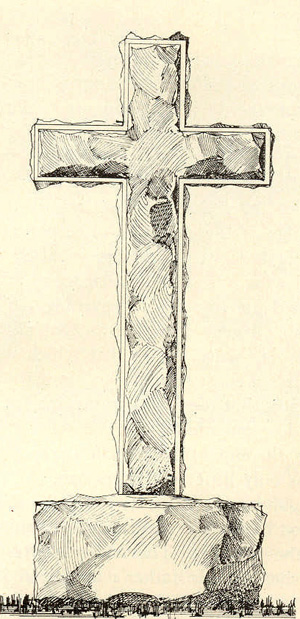

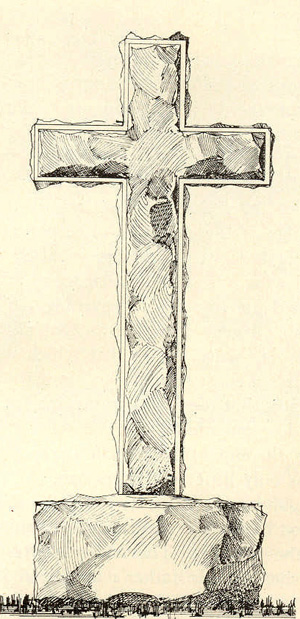

The necessary permission has been secured for the erection of a cross, which will be

ten feet high, of rough-cut New Hampshire granite with a chiseled edge, and will bear

upon its base the inscription, “HE CALLETH HIS OWN BY NAME”.

Those who wish to join Mrs. Greer in this splendid movement may send their

contributions to her at 7 Gramercy Park. About six hundred dollars is needed.

|

| The above image does appear in the original work with this caption: “The Cross for the Potter's Field.” |

Mission News May 1907:

The fund for the cross at the Potter’s Field, which Mrs. Greer was seeking to raise, was quickly subscribed. It is hoped that the cross will be in place in time for it to be

dedicated by Bishop Greer on the afternoon of Trinity Sunday.

The usual custom is to

have the annual Confirmation at the City Home for the Aged on that day, and many of

our friends go to the service.

This year the Confirmation Service will be held earlier in

the afternoon, and the friends who accompany us – an invitation is extended to all – will

be taken by boat directly to Hart’s Island for the service there.

Mission News June 1907:

It is greatly regretted that, owing to a delay on the part of the stone-cutters, the

cross for the Potter’s Field could not be in place in time to be dedicated on the afternoon

of Trinity Sunday, as it had been planned.

The dedication will take place some weekday

in June, as we cannot now give definite notice of the time, if those who would like to be

present will send their names and addresses to the Superintendent, the Rev. Mr. [R. B.] Kimber,

he will notify them by post. Cordial invitation is extended to all those who are interested

in this good work.

The 1906-1907 annual reports of the Rev. Thomas McCandless:

* The Branch Workhouse, Hart’s Island 1906-1907

. . . . During the past year the census of the Branch Workhouse has ranged from 400 to

700. Of these, excepting the twenty-five or thirty women needed in the island laundry,

the greater part are elderly men, who return with sad regularity to serve term after term as

vagrants. They usually keep away for the midsummer months, but the first touch of frost

hurries them back to what is their only real home.

The younger men, numbering perhaps 100, do the heavier work, such as digging

the trenches in the Potter’s Field. The new ice-plant, planned to supply the institutions of

the different islands, requires the labor of many. These men are more active offenders

against the law, and are being punished for disorderly conduct, drunkenness and nonsupport.

|

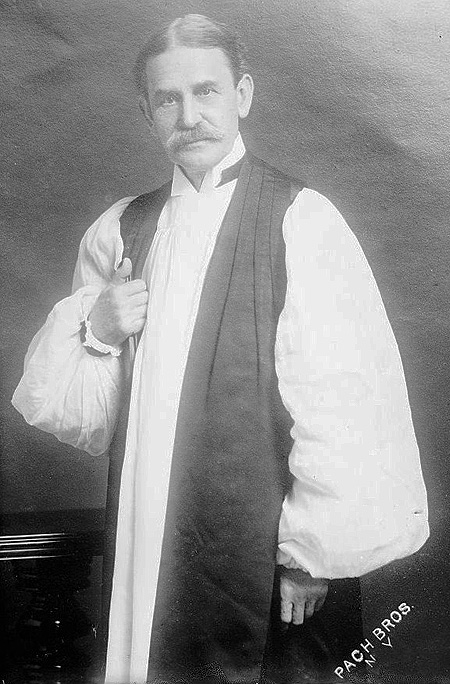

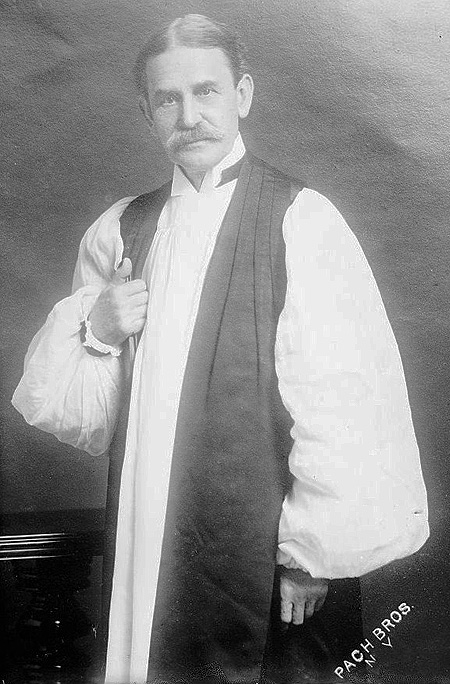

| In 1903, the Rev. David Hummell Greer, then rector of St. Bartholomew's Church, was elected Bishop Coadjutor for the New York Episcopal Diocese, and five years later succeeded Bishop Potter upon the latter's death.The above image & caption do not appear in the original work. |

The most deserving and most hopeful of all the inmates are the eighty to 100 boys

who are segregated in what has been, euphoniously but mistakenly, called the Reform

School.

This is merely part of the Workhouse where the boys are kept. Those not

graduates of the public school are required to attend daily one session of the school

maintained on the island by the Department of Education. This is the extent of the

“reform.”

. . . . During the past year, by interceding with the magistrates, the release of

about twenty men was secured. Of course, it is needful to exercise the closest scrutiny

before undertaking such a mission. That in this we have been sufficiently careful is

shown in the fact that no magistrate has ever refused our request and that no prisoner so

released has ever been recommitted.

Lest such a chaplaincy might seem too secular, too busy with the cares of this world,

we have tried to square our Sunday preaching with our week-day practice, and to

transfigure love for humanity into love for humanity’s God. Our services are reverently

followed and shared by the inmates who worship with us. Mr. Gethin, our organist,

renders invaluable aid in making our singing hearty and devout. On a few holy days, the

Rev. H. St. George Young has visited us and administered Holy Communion, and on

Trinity Sunday it was a privilege to present to Bishop Greer, for Confirmation, a class of

three men, two women and five boys — the first Confirmation class on Hart’s Island.

[Editorial Note:] The Confirmation took place at the Chapel of the Good Shepherd on

Blackwell’s Island May 26, 1907, the Rt. Rev. David Hummell Greer, Bishop

Coadjutor of the Episcopal Diocese of New York presiding. Greer would become the

8th Bishop of New York the following year following the death of Bishop Potter. . . .

*The New York City Reformatory 1906-1907

. . . . the year just ended has also shown some basis for our

optimism. For we have progressed. To begin with, the number of inmates is now on the

average 300, twice that of a year ago. And instead of the indiscriminate commitment of

“boys” of thirty and boys of fifteen, hardened criminals and unfortunate children, we now

receive only first offenders. So our standard of admission is a year higher. Again, to earn

his recommendation for parole, a boy must now have 1,200 instead of 900 merit marks, a

full month’s extension of the minimum term. That is a step, but only a step, in the right

direction, for in neither three nor four months’ time can any permanent reform be

affected in a boy’s character.

|

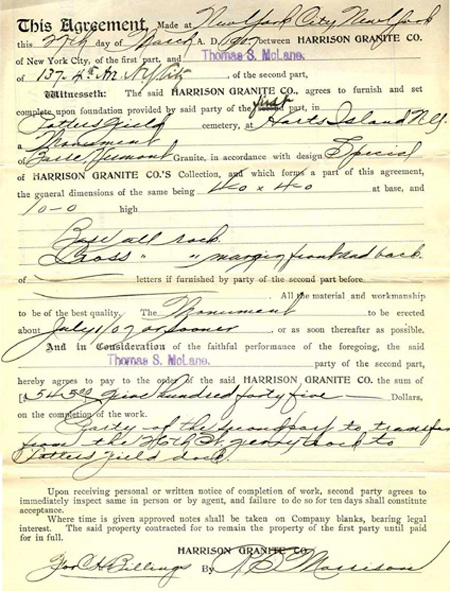

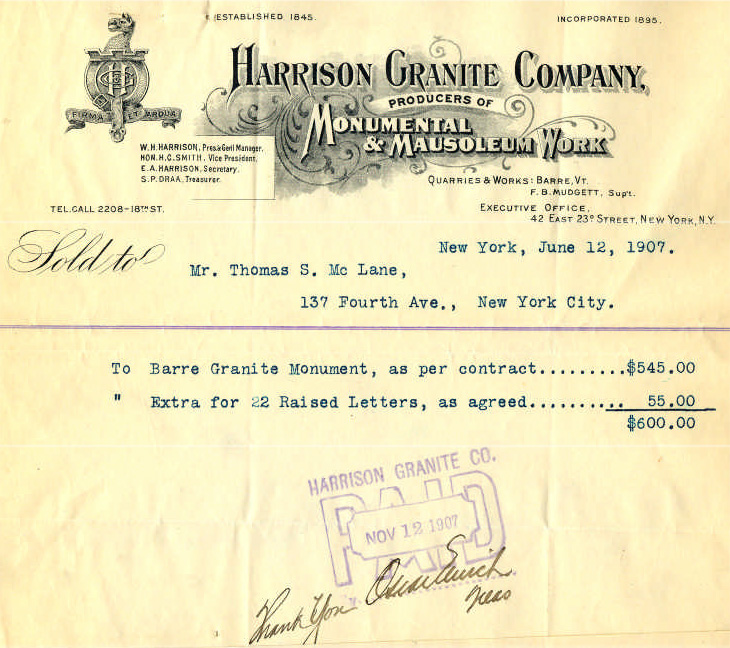

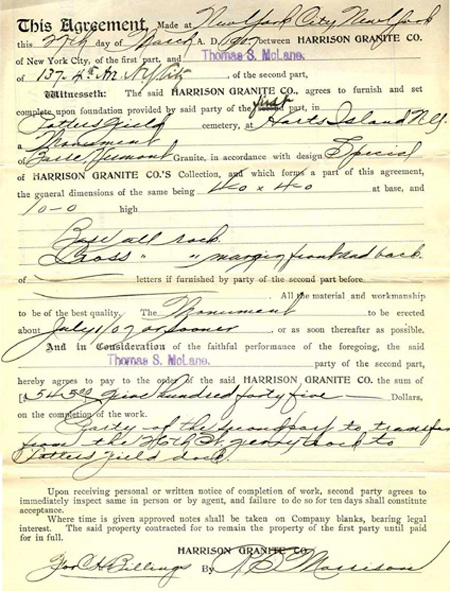

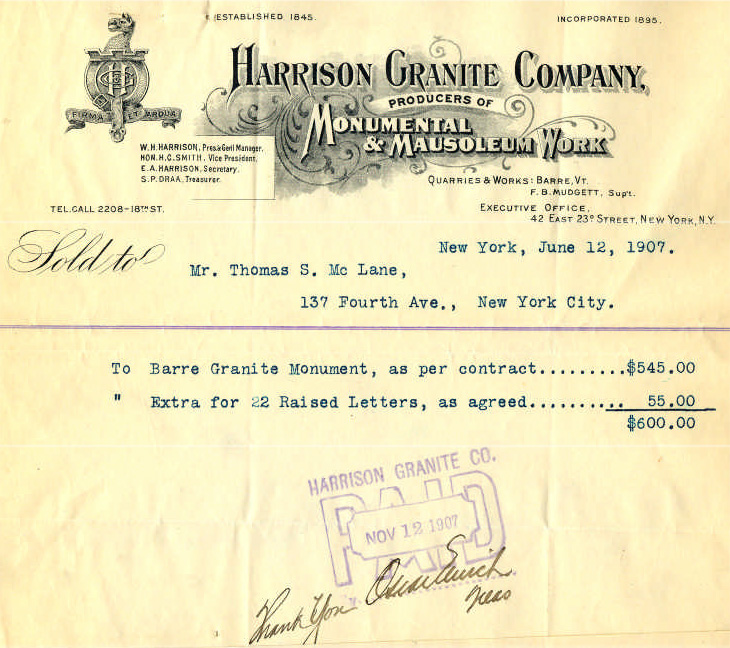

| The above image of the cross contract does appear in the original work with the notation "Attached is the 1907 contract with the Harrison Granite Company for the fabrication and

erecting of the monument at The Potter’s Field on Hart’s Island." |

There are, then, both virtues and faults in this new attempt to deal with a rapidly growing

class of criminals, whose offences demand and deserve some middle ground of

punishment between the House of Refuge and the Penitentiary. First let us enumerate our

good points:

- The Reformatory offers another chance to the erring boy. The first misstep is no longer

to close against him the door to honesty and usefulness. If he has broken the law through

accident or thoughtlessness, he is here taught the consequences of apparently trivial

breaches of morals and laws. If he has deliberately chosen the evil rather than the good,

he is here enabled to balance the right and the wrong, and to make the right and logical

choice.

- The length of a boy’s stay in the Reformatory depends largely upon himself. His own

conduct, in his work and study, is the basis of decision as to the length of his term.

- The head of the Reformatory, Mr. Van De Carr, has already impressed himself upon

the minds of the boys as being just and kind in his administration. This estimate, coming

from the boys themselves, means that in its head the institution contains an element of

present and future usefulness.

So much for present virtues! There ought to be, and there will be, more than these. The

boys should be given a training in the personal and social decencies that is out of the

question with the present lack of equipment.

|

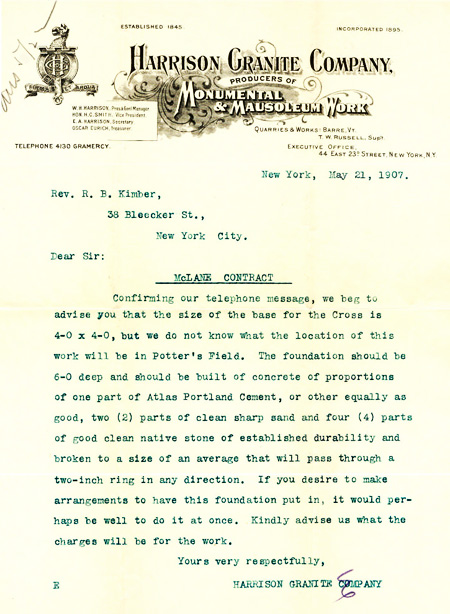

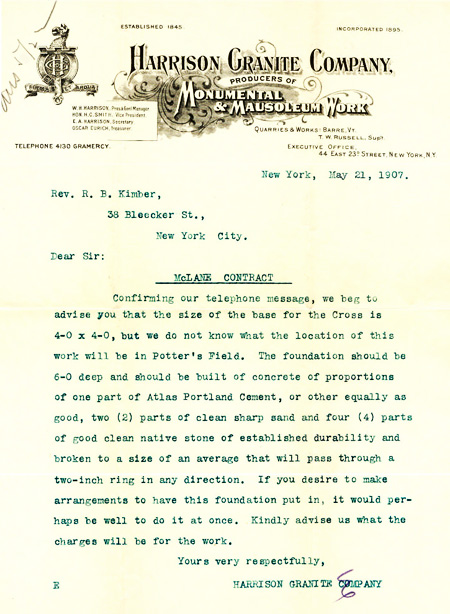

| The above self-explanatory image of the letter about the cross contract does appear in the original work |

The faults of the institution are apparent to the most superficial inspection. Among

others, the following seem most to deteriorate the standard of the Reformatory:

- The overcrowding of the boys in buildings that no money or pains could make suitable

for their present use. Under any conditions, the dormitory system is an unmixed evil, but

where boys are herded like cattle into cots only a few inches apart, physical

contamination is unavoidable.

- There is no proper system for the after-care of those paroled. The parole officers,

Messrs. Bliss and Hogan, do good and faithful work. But it apparently was not the plan,

in starting this institution, to provide homes and employment for such boys as has neither

money nor friends. Hence, now and again, some unfortunate boy remains in the

Reformatory for a period out of all proportion with his offence, simply because there is

no one to promise him employment and a home.

- Another fault that touches very closely upon the work of a chaplain is that the boys

have little or no esprit du corps; there is among them no notion at all that the good of

each is the good of all. Hence all their thoughts and plans center in their own release; that

their behavior after parole may help or hinder those to follow, causes them no concern.

Almost none of the friendless boys who are helped by one or another to obtain their

parole ever show any evidence of gratitude. They disappear at once, and make no effort

to observe the terms of parole.

. . . . When a boy is paroled on condition that

someone provides his fare to his home, our Ex-Convict Fund is called upon. Yesterday

we sent a Jewish boy to his parents in Montreal. Most of those so aided have shown a

lively sense of gratitude by returning the amount we gave them.

|

| The above self-explanatory image of the bill payment does appear in the original work |

And in this connection,

we take pleasure in testifying to the multitude of boys from Hart’s Island, who has been

restored to honesty and usefulness through the Chrystie Street Home. Mr. Wallace

Gillpatrick, the Head of the Home, works with me in this, and it is but justice to say that

without his cooperation we could do little for the homeless boy.

Mission News November 1907

The Rev. Thomas McCandless, for the past two years Chaplain at Hart’s Island,

has been transferred to Ellis Island to succeed the Rev. Mr. Campbell. He enters upon his

new duties November 1st.

From the 76th Annual Report of the New York Protestant Episcopal City Mission

Society by the Superintendent the Rev. Robert B. Kimber:

“More than 5,000 persons have been laid to rest in the city’s burial ground – the

Potter’s Field – and over each one interred there the Burial Office of the Church has

been read. No longer is their resting-place unmarked, for there now rises from the knoll,

plainly seen by the passing ships, a large granite cross, bearing the inscription, “HE

CALLETH HIS OWN BY NAME.” This symbol of the resurrection is the pledge to those

who lie there of their heritage in the Christian’s hope.”