|

Part 1 of a 3-part web version of a paper presented Nov. 15, 2013 at Researching New York 2013 by correctionhistory.org webmaster. Clicking lower case Roman numerals in Parts I and II accesses respective endnotes in Part III. Clicking that citation's numeral in Part III returns you to your place in Part I or II. A list of links

to access any of the 3 parts appears at bottom of each page.

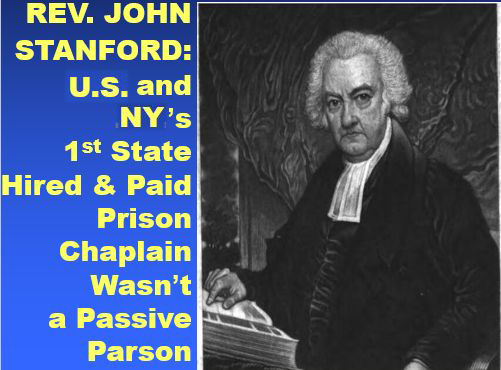

REV. JOHN STANFORD: U.S. & NY’s 1st STATE-HIRED & PAID PRISON

CHAPLAIN WASN’T PASSIVE The printed copies of the monograph presented at the Researching NY 2013 conference did not include images. This web version includes images both for their design value in this visual medium and as a way of illustrating relevant aspects of the life and times of Rev. John Stanford.

n

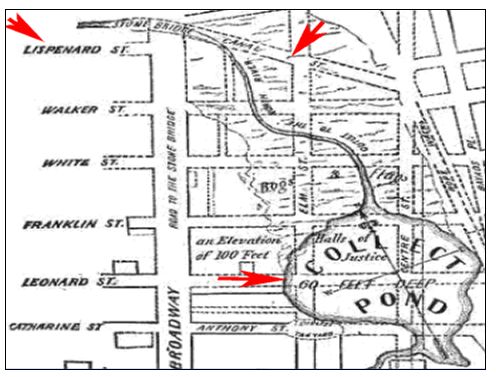

The city’s population was

gaining on the quarter-million mark while across the East River the village of Brooklyn

was emerging as a city, and n

The NYC canal which had been

dug to drain the little lake called Collect was now filled in (as was the pond

itself). The street which took its name from the vanished canal was

experiencing a building boom as a commercial thoroughfare. On Lispenard Street, a block south of busy Canal Street, at 2

o’clock in the afternoon that New Year’s Day 1834, some 150 children wearing New

York Orphan Asylum uniforms were gathered in front of the home of their venerable

chaplain.

Three red arrows have been added by the webmaster for this presentation to point out certain features in particular. The bottom arrow points to where The Collect pond had been. Of the two arrows at the top, the left one points to Lispenard Street on which Rev. Stanford lived and the right one points to Canal Street. Where Canel Street intersects Broadway near the top left corner, the map indicates a stone bridge had been in the vicinity of what the previous illustration depicts a thriving business intersection in 1834.

They were there, with the asylum’s superintendent and

teachers, to wish the minister a happy New Year. Infirmities of age now kept

the octogenarian mostly house-bound. Since he, whom some of the younger ones

called “old Father Stanford,” could no longer come to them, they had come to

him. They came to wave to him as he watched from his front window,

waving back. They came to sing for him the hymns he had taught them during his

long service at their orphanage. From his front room he joined in singing the

hymns, if only silently in his head as “his children” raised their voices in

praise of God. In March 1806, Mrs. Isabella Graham, president of the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children, found herself in charge of six children whose widowed mothers had recently died. Rather than put the children in an almshouse, she enlisted her daughter, Divie Bethune, her recently widowed friend Elizabeth (Mrs. Alexander) Hamilton, and other prominent ladies to create the NYC Orphan Asylum Society. Soon the six children were living in a small house in Greenwich Village. Thus began the child caring institution known today as Graham Windham. The Rev. John Stanford was often involved in the orphanage's activities and authored one of its earliest histories.

Stanford’s neighbors on Lispenard Street stood in their doorways

or opened their windows to watch and listen. When, all bundled up against the

chill air, the ancient cleric stepped onto his front stoop, the spectators

joined the children in applauding his making an appearance. He thanked the

youngsters, acknowledged the adults, and delivered a few remarks of spiritual

encouragement before handing out small gifts to the boys and girls: Children,

O my dear children, pray to God for new hearts. Seek the Lord while He may be

found. I shall meet you no more until the trumpet of the archangel wakes the

slumbering dead. May I then meet you in your Father’s House in Heaven. [i] Distribution at the Researching NY 2013 history conference of copies of the printed monograph about Rev. John Stanford was accompanied by a PowerPoint presentation highlighting particular points made in the research paper by this site's webmaster.

Thirteen days later “old Father Stanford” died. Who was this late 18th and early 19th

Century man of God that we, in our fast-paced 21st Century whirl of

a world, should pause to take note of him? This Researching New York 2013 presentation argues that the Reverend

John Stanford deserves to be recognized as the first state-hired and state-paid prison chaplain

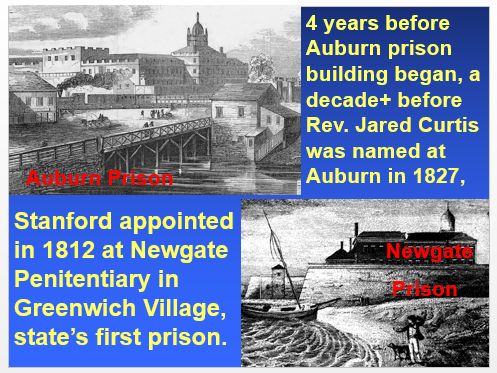

in New York State and in the United States of America. Generally that distinction has gone to the Reverend Jared Curtis by

virtue of his having been added to the payroll at New York State’s Auburn Penitentiary full-time for

$200 a year in 1827. Distribution at the Researching NY 2013 history conference of copies of the printed monograph about Rev. John Stanford was accompanied by a PowerPoint presentation highlighting particular points made in the research paper by this site's webmaster.

But research shows that four years before Auburn Penitentiary construction

began and a decade and a half before Rev. Curtis went on that state prison’s

payroll, the Rev. Stanford was being paid by NY's first state penitentiary,

“Newgate” in Greenwich Village, to render chaplaincy services. The question of who should be recognized as the first

government hired-and-paid prison chaplain in NYS and the country may turn on the

issue of criteria -- part-time vs. full-time and the servicing of one

institution exclusively vs. servicing multiple institutions on a rotating

schedule. Distribution at the Researching NY 2013 history conference of copies of the printed monograph about Rev. John Stanford was accompanied by a PowerPoint presentation highlighting particular points made in the research paper by this site's webmaster.

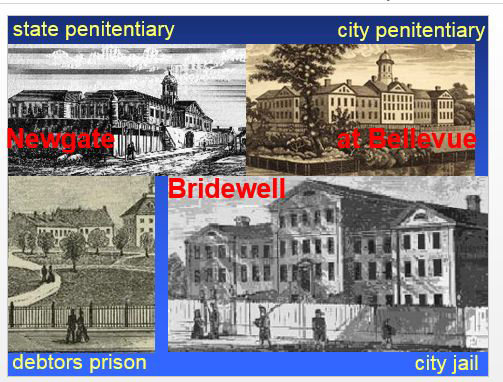

Rev. Stanford made the rounds of various institutions in NYC,

providing religious services to their unfortunate inmates and patients,

including the Almshouse, Bellevue Hospital, Debtor’s Prison, State Prison,

Military Hospital, Magdalene House, and Bridewell Jail, among others.

The

separate institutional annual stipends, though individually very modest,

collectively enabled him to make a living and support his family, albeit in a

frugal life style. This paper argues that government payment for rendering

religious services is the decisive factor to be considered, not whether the hired

chaplain worked full time exclusively for the prison or worked less than

full-time and not exclusively.

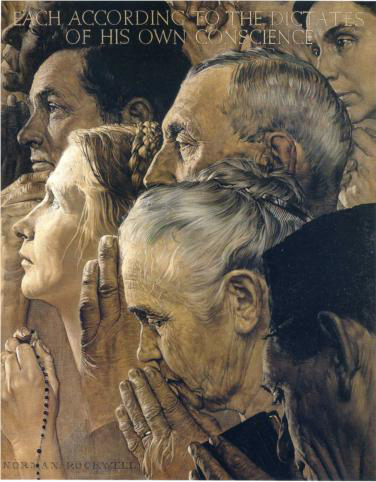

In what serves as a classic example of centralized national government incompetence, various federal agencies all rejected famed illustrator Norman Rockwell's free offer to paint visualizations of the Four Freedoms which FDR told Congress on Jan. 6, 1941, that the world sought despite the rise of tyrannical dictatorships. Only after overwhelming public response to the Saturday Evening Post's publication of the paintings did the D.C. bureaucrats wake up and play catch-up, co-opting the images for hugely successful war bond drives. Rockwell's Four Freedoms have since become part of American ideals' iconography.

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or

prohibiting the free exercise thereof . . . . . The United States' long tradition of varous government agency chaplaincies reflects American

society’s decision, despite “non-establishment” clause concerns, to give

priority to the “free exercise” clause, recognizing that military service

personnel, inmates in prisons and jails, patients confined in government health

facilities, etc., simply cannot have “free exercise” of their religion if

access to religious services is not provided. The high courts of the land have

consistently upheld prison chaplaincies as “constitutionally permissible

accommodation.” The question raised in Cutter v. Wilkinson was: Did a federal law prohibiting government from burdening prisoners' religious exercise violate the First Amendment's establishment clause? In a unanimous opinion delivered by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Court held that the law was an effort to alleviate the "government-created burden" on religious exercise that prisoners faced. (The preceeding summarizes a page about the case on the Chicago-Kent College of Law Oyez site.)

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg,

who wrote the deciding opinion, declared:

"Our

decisions recognize that there is room for play in the joints between the

clauses, some space for legislative action neither compelled by the Free

Exercise Clause nor prohibited by the Establishment Clause." [ii] The debate over government providing chaplaincies as an accommodation in

special settings, such as in penal institutions, has been ongoing since the

founding of our constitutional republic.

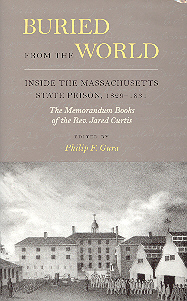

UNC Prof. Philip F. Gura edited the book containing Rev. Jared Curtis's notes profiling

hundreds of inmates at the Massachusetts State Prison in Charlestown, to which the cleric was appointed chaplain after his relatively brief stint in a similar capacity at NY's Auburn penitentiary.

Whereas Curtis’ service at Auburn Penitentiary was relatively brief (about

two years) before his moving to similar duties at a Massachusetts prison,

Stanford continued in his simultaneous multiple New York chaplaincies for

decades, earning the title “Chaplain to the Humane and Criminal Institutions in

the City of New-York,” accorded him by the editor of his memoir, the Rev.

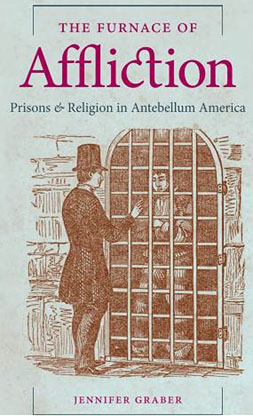

Charles G. Sommers, pastor of South Baptist Church, NYC. American religious historian Dr. Jennifer Graber of the University of

Texas recognizes that studying Stanford serves well those 21st

Century researchers interested in understanding Jacksonian era penal theory and

practice.

In her well-researched and fact-filled book on prisons and religion

in antebellum America, The Furnace of Affliction, she wrote of Stanford: His

role as one of the nation’s first prison chaplains – at a time when the course

of prison discipline was so fiercely debated – makes his Newgate tenure of

particular interest.[iii]

The above image is derived from one appearing

on the Google eBook preview presentation of excerpts from

professor Jennifer Graber's book published in 2011 by University of North Carolina Press.

He appears on 30 pages scattered

throughout her book’s 208 pages of main text and notes.

Unfortunately,

Professor Graber’s grasp of his mind-set is heavily influenced by her own mind-set.

That, in turn, appears strongly influenced by the social theories reflecting

deconstructionist analysis associated with such post-structuralists as Michel

Foucault. Viewed through the lens of these interpretative approaches, the

18th and 19th Century Christian penal reformers were

mistaken when they thought their efforts to make the penal systems more humane

were motivated by their desire to fulfill Christ’s command to befriend the

unfriended. Yes, Jesus had taught that when they fed the hungry, clothed

the naked, visited the sick and imprisoned, rendered comfort to even the least

among them, they did so unto Him and would be welcomed into His Kingdom.

But

that wasn’t what their service to the needy, downtrodden and outcasts was all

about, according to post-constructionists.

No, it was about perpetuation of

power to oppress. Graber writes: When her book was pubishedin 2011, she was an assistant professor at

the College of Worster. She subsequently joined the University of Texas College of Liberal Arts at Austin faculty. Professor Graber teaches undergraduate classes on the history of religion in the U.S. and on Native American religions. She teaches graduate seminars on religion and violence and approaches to the study of religion in the U.S.

.

. . . I argue that the reformers theology of redemptive suffering not only

allowed but actually demanded these degrading practices [social isolation,

awful uniforms, the lockstep, limited corporal punishments]. .

. . . their theological notion of what it meant to be human necessarily

involved a statement of degraded status: human beings are lower than God. While

prisoners’ humanity protected them from inordinate cruelty, it also demanded

regimes designed to make them realize that they were less than God. .

. . [the reformers’ theological] affirmations also demanded painful

acknowledgment that human beings are not God. .

. . prison was a training ground for lawbreakers . . . to understand every

human being’s degraded status before a God that governed the universe . . . .

Their theological understanding of inmates’ humanity had a way of underwriting

hard and degrading regimes instead of challenging them.[iv] Assessing Foucault's thought separate from his life-style is difficult, if not impossible. His immersion in consensual same-gender sadomasochistic sex and experimentation with drugs, including LSD, expressed his rejection of societal controls which his writings detected and dissected. His deliberate engagement in promiscuous "unprotected" practices, which consciously courted the risk of contracting AIDS (from which he eventually died at age 54), reflected his nihilistic fascination with suicide.

Now I confess that on those rare occasions when I attempted

to indulge the delusion of being God-like, my late wife of 55 years quickly

disabused me of that exalted notion.

Most folks looking around them at the

state of humanity, as it is currently and has been in history, have little

difficulty concluding our species is something less than divine. Indeed, we

prize heroes and saints precisely because they serve to reassure us that our

human race does possess some capacity for nobility and self-sacrifice. That is

so today, and was true two centuries ago. The inmates of Newgate needed no sermons

or scripture to convince them that humankind’s nature – theirs included -- was

far from perfect. The limited scope of this paper does not permit me to

critique deconstructionist misinterpretations of 18th and 19th

Century penal reformers and ministers’ theological motivations. It suffices

that, in the interest of providing some contextual reference, I call attention

to a current academic practice of faulting them for not behaving like modern

militant activists “challenging” the system. The fact is that Stanford – born Oct. 24, 1754, in Surrey,

England -- did during his long life often chose the more challenging course

before him . . . . [Continued in Part 2.]

|