Stacy Horn's New Book Harkens Back to Era of

1st Hart History Tour & Academy Archival Research

|

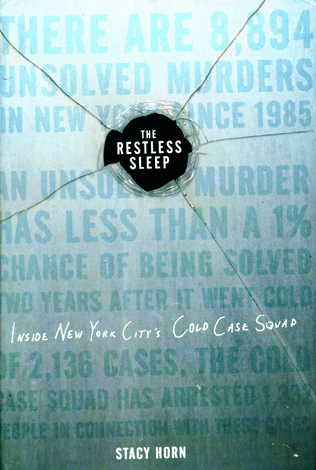

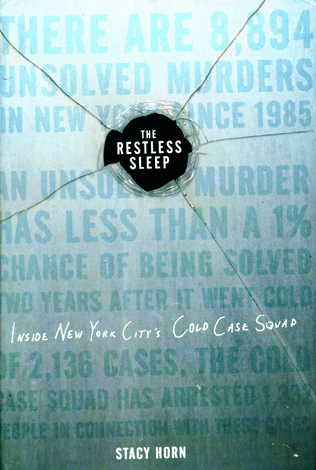

Image of front cover of Stacy Horn's new book debuting July 2, 2013.

|

|

NYCHS' first researcher at archives in Correction Academy, Stacy Horn of EchoNYC, wields her No. 2 pencil making notes while studying a 1872-1875 ledger of Potter's Field burials.

| Authoress

was there at

start of organized

New York

Correction

History

outreach

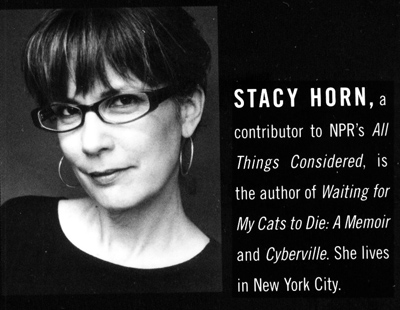

Authoress Stacy Horn, who has been a participant in New York Correction History Society (NYCHS) outreach programs from their beginning, has written another book in which she references a bit of that history.Her latest tome, entitled Imperfect Harmony: Finding Happiness Singing With Others, published by Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, is due to debut July 2nd.

She was among three dozen New York historians, academicians, graduate students, genealogists and other serious researchers who participated in the first-ever history tour of Hart Island and the Harlem Courthouse jail Thursday, April 27, 2000.

|

In the winter of 2000, a Correction Academy small conference room became temporarily a Research Reading Room for the first archives researcher, Stacy Horn, studying the 1872-1875 Potter's Field burials ledger and other Hart Island-related materials (books, clips, photos).

| Organized by NYCHS, which had been formally established only about nine months earlier, the tour was conducted through the good offices of the New York City Department of Correction (DOC) and in coordination with the City University of New York Americanist Group, part of the NY Metro Chapter of the American Studies Association.

NYCHS initiated the event to promote the academic community's interest in recovery and preservation of correction history in New York. Due to increased security concerns, such tours no longer take place.

Later, during the winter of 2000, Ms. Horn became NYCHS' first researcher when, having completed the registration procedure, she began making notes at the DOC Correction Academy as she perused Hart Island-related archieved materials. These included the archival treasure, a 1872-1875 ledger in which had been recorded Hart Island Potter's Field burials.

Ms. Horn was welcomed by the then NYCHS curator, Deborah Kurtz who, as then DOC Deputy Commissioner for Training, Organizational Development and TEAMS, had charge of the Correction Academy.

|

Stacy Horn, right, discusses with then NYCHS curator, (now former) Deputy Commissioner Deborah Kurtz, interesting photos among the Hart Island (Potter's Field) materials made available for research viewing.

| Also greeting her was (now retired) Academy Captain Ralph Greenberg.

Stacy, who identifies her main occupations as "writer and cat-butler," also operates a social network site called EchoNYC. It is described variously as a bulletin board system, an Internet salon, and an on-line communications virtual community. Founded by her in 1990, its members are sometimes called Echoids. She has suggested the letters in "Echo" stand for "East Coast Hang Out."

Her new book, Imperfect Harmony, makes the point, among others, that choral singing can become an instrument for social justice, for healing and for empowering those who feel disenfranchised. There was an oblique reference to that in a post by her on her web site and incorperated into one of her earlier books, Waiting for My Cats to Die!, excerpted here with permission.

The Hart Islander

|

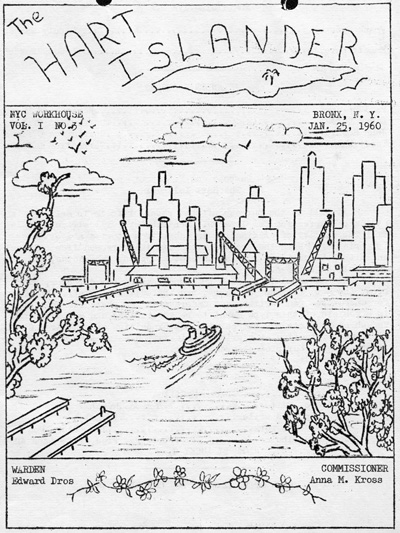

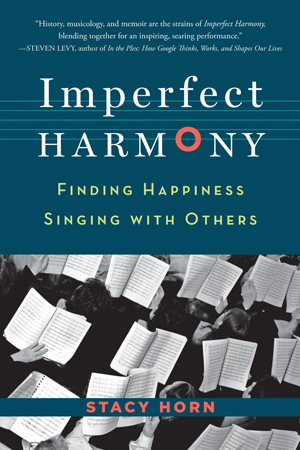

Front cover, The Hart Islander, Jan. 25, 1960.

| I’d come across a prison choir while working on the Hart Island chapter of my book, Waiting For My Cats to Die. Hart Island is the site of New York’s Potters Field and it’s maintained by the Department of Correction.

While looking through the Department of Correction archives, I came across a crude but endearing inmate-produced magazine called The Hart Islander (inmates were housed on the island for a time).

The December 25, 1959 issue begins, “Our first issue—our baby—our sweetheart,” and there’s a description of their Christmas show:

|

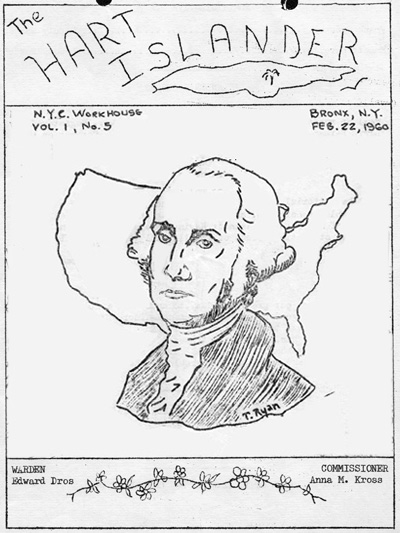

Front cover, The Hart Islander, Feb. 22, 1960.

| “From it’s [sic] spirit-lifting choral beginning to it’s [sic] shoulder shakin’, moving end, the X-mas show was completely enjoyable …

“The future for Three Notes would be assured with proper management and polish … their delivery of Walking by the River and I Laughed at Love were quite good, perhaps better, than vocal groups on the scene today …

“Mr. Parrish does very good work with Caravan and All the Way with a most interesting vibrato that could sell records.”

|

|

Click above image to acess. select, hear Grace Church Choral Society excepts on its web site. Use your brower's "back" button to return.

|

|

The authoress of Imperfect Harmony: Finding Happiness Singing With Others sings in the Choral Society of Grace Church, Manhattan. Click the above image from its web site to access its home page. Use your browser's "back" button to return.

| In 2001, the news media ran a story about two detectives arranging for a deceased WWII vet to receive what was conveyed as the honor and dignity of a proper burial elsewhere rather than in Potter's Field. Horn, who among her many hats also wears the cap of commentator contributing to NPR's All Things Considered program, felt prompted by that aspect of the news reports to speak up in defense of Hart Island.

In Defense of Potter's Field.

Here is the text of her commentary broadcast on WNYC July 25, 2001:

|

The above Stacy Horn photo and bio note are from the jacket of her book The Restless Sleep.

| Potter's Field

ANNOUNCER: This summer, two New York City detectives arranged for the body of a World War II veteran to be moved from the city's Potter's Field to a veterans cemetery. Commentator Stacy Horn knows the move was well intentioned, but she wants to defend the honor of Potter's Field:

---- ---- ---- ---

HORN: The term "Potter's Field" comes from the Gospel of St. Matthew. Judas couldn't get rid of the thirty pieces of silver he'd been paid to betray Jesus fast enough. He threw the money into a temple, but the priests didn't want the blood money either. They ended up using it to buy land from a local potter to use as a cemetery for strangers. Potter's Fields are now traditionally where the poor, unclaimed, and unidentified are buried.

|

The gray granite Charity Hospital on Blackwell's Island (now Roosevelt Island), from whence came the first person's remains to be buried on Hart Island by DOC, was said in its time (19th Century) to be the largest hospital in America, able to accommodate 1,200 patients comfortably.

| In New York, Potter's field is located on Hart Island. I've been to Hart Island. It looks like an abandoned country estate where the landscape has been allowed to grow back to what it might have looked like before we got there. The buildings have that particular bittersweet beauty of crumbling decay. Wildflowers grow everywhere, and you can hear the sound of the sea from practically every point on the island.

Louise Van Slyke, a lonely 24 year old who died at Charity Hospital in 1869 in the first civilian to be buried in the Potter's Field on Hart Island. Since then she's been joined by more than three quarters of a million people, and 1,500 to 3,000 people are added yearly, and in a dignified and respectful manner.

The first sign of respect that New York shows its citizens who die alone is in the very fact that New York is one of the last major cities to bury the poor and unclaimed instead of cremating them.

The burials are overseen by the Department of Correction and they are conducted by inmates of Riker's Island.

The convicts treat the dead with tender care. It upsets and haunts them to bury the people that everyone else has forgotten, especially the babies that are buried in the children’s trenches, which hold 1,000 each.

The prisoners leave modest offerings of fruit, flowers and rosaries at the various monuments around the island.

|

Academy Capt. Ralph Greenberg, now retired, welcomed authoress Stacy Horn as the archives' first researcher.

| Perhaps New York City and the Department of Correction will be less than pleased to have a burial on Potter's Field described as perfectly proper and honorable -- they might not want a run! But it just happens that sometimes we find ourselves at the end of our lives alone, or poor. God bless the people who have their friends and family around them, and enough money for caskets that archeologists might be digging up way into the future, but life doesn't always work out so nicely for everyone, and I don't think the people buried there, or their families, have anything to be ashamed of.

|

In 2005, Viking, part of the Penguin Books Group, published her The Restless Sleep: Inside New York City's Cold Case Squad. In the Appendix Notes section, NYCHS' www.correctionhistory.org was listed among the 20 web site used as resources.

Arraignments & DOC Court Pens

On Pages 220 - 224 appeared a description of circa 2004 Manhattan Central Booking procedures, including those involving Correction personnel. With permission, that account -- reasonably accurate for a non-law enforcement professional -- is reproduced here. While the routine's details are familiar to most veteran DOCers, many other visitors to our web site may not be so knowledgeable and therefore may appreciate the step-by-step reportage in colloquial speech rather than in the jargons of the various arraignment scene practitioners. What the telling lacks in technical precision is more than compensated for in its vividly conveying the "look and feel" of the process.

|

Above is an image of the front cover of the 2005 book from which the excerpt provided here was taken, with permission. Authoress Stacy Horn retains all rights.

|

Every borough is a little different, but from here to Arraignment

Court, the Central Booking process is basically the same. The following describes what takes place in Manhattan when arrestees are

brought to 100 Centre Street, aka the Tombs.

The prisoners are taken to what’s called the sally port, the place

for on-loading and off-loading prisoners. (Sally port is an archaic

term that refers to the opening in a fort through which soldiers

“sally” forth to attack or defend.)

Inside, each prisoner gets a movement slip with a barcode, and at every step in the booking process

that barcode will get scanned in and time-stamped. It’s like being on

a conveyor belt of corrections, it’s so efficient. Everywhere you go

prisoners stand in small groups connected like chain gangs, quietly

waiting.

While this is going on, an independent outfit called the

Criminal Justice Agency gets the prisoner’s rap sheet and begins to

prepare a report for the judge who will be making a decision about

bail. Every few feet there is some sort of security device — people,

cameras, locked doors where you must be buzzed in and out.

Fingerprints are electronically scanned on a red, glowing surface.

You can’t turn a corner without hitting a new set of holding cells.

Some are for men, some are for women, and some are called special,

where they put people who have medical problems, are openly gay,

or in the case of informants, are in protective custody. The last thing

they want to do is endanger a valuable informant. It’s hard to meet

the eye of anyone sitting in a holding cell, too. They’re caged.

|

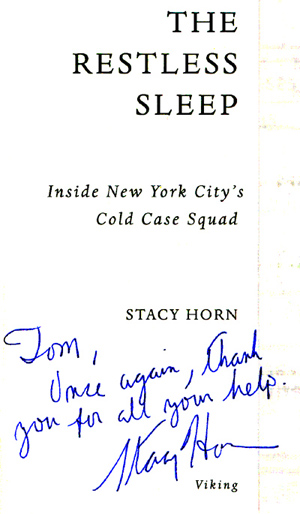

Above is an image of the title page of NYCHS' copy of the 2005 book from which the excerpt provided here was taken, with permission. Authoress Stacy Horn retains all rights.

| Everyone looks down, except for a few people who are trying to

look tough or others who appear permanently damaged. One girl

looked up through the bars. Her eyes were excited; it was as if her

heart was racing. An officer checked some papers. She was there for

selling fake watches on Canal Street.

After the prisoner gets his movement slip he goes to Medical first,

for an initial screening from an FDNY EMT. Next, he stops by the

room that houses Criminal Justice Agency personnel.

Then he’s

searched. It’s a standard metal scan and pat search or frisk. Strip

searches at this point are no longer conducted without probable cause.

Even though the place is spotless, occasionally it smells like

urine.

The next room is the one formally referred to as Central Booking.

It’s a large space that’s completely encircled by still more holding

cells. Here the prisoner will meet with his lawyer. If he doesn’t have

his own lawyer and is assigned a member of Legal Aid, he’ll meet

with them later, in one of the court holding cells upstairs. The court

draws up a docket number, and the prisoner is put in a cell to wait.

At this point, the arresting officer will leave. . . . .

In movies, the police can be either heroes or villains. The correction guys are almost always bad guys. Prison guards -- a term they

won’t even use anymore, it’s always correction officer—are frequently as vilified as the prisoners they care for.

|

Above is an image of the north building of the current Manhattan Detention Complex built in 1989.

| But the correction

officers at the Tombs are extremely polite to everyone who is

brought in. Perhaps extreme politeness is how you repeatedly get

through this awkward situation. A correction officer offers another

explanation. “They’re innocent,” he says of the prisoners here. This

is America. No one has been to trial and sentenced—innocent

until proven guilty. Everyone in the custody of the Department of

Correction at this point is innocent, so, to the best of their ability,

Correction treats them as such. “If the prisoner acts up, though,”

[a Cold Case Squad detective] says, “everything changes. I’ve seen corrections officers

clock guys.”

When all the prisoner’s paperwork is together and complete, a

court officer will tell a New York police officer to bring the prisoner

back up two levels from his Central Booking cell to be arraigned.

The prisoner is signed out and brought upstairs to another set of

cells with rooms where he can talk to his lawyer. From there he goes

to court.

Arraignment Court is just like the old TV show Night Court. It’s a

courtroom like any other courtroom, except not as fancy. This is the

Grand Central of courtrooms; it’s a bit run-down, reflecting the

amount of traffic they get daily. Most of the people here look bored.

Or tired. The court personnel look professional.

|

Above is an overall view of the Manhattan Criminal Courthouse,

100 Centre Street, originally built in 1938-1941, situated on the block surrounded by Centre, Leonard, Baxter and White Streets. It currently houses the Criminal and Supreme Courts, the District Attorney, Legal Aid, offices for the Police Department, Departments of Correction and Probation

| When their number is called, the prisoner goes up before a judge, and their lawyer

and the ADA make their case about bail. It would be unusual to get

bail in a homicide case today. “That’s why there are all these guys

running around wanted for murder, because they were given bail

years ago,” [the Cold Case Squad detective] says. These days, in spite of any defense attorney’s arguments, the DA won’t offer it, and the judge won’t grant it.

Instead, the prisoner will be committed to the New York City

Department of Correction until his trial. He will be handed over to

the Department of Correction along with an accusatory instrument

(anything that gives Correction the right to hold the inmate, a court

order, an out-of-state warrant, or a parole violations warrant, for example). He’s their responsibility now

The whole process is conducted like a two-leg relay race. They’ve

got twenty-four hours from the moment of arrest to get the person

in front of a judge, and then the Department of Correction has

twenty-four hours to process and house them either in the Tombs

or at one of roughly nine facilities at Rikers Island.

|

In the above aerial view of Rikers Island, which happens to be part of the Bronx, can be seen the bridge, left, extending south toward Queens. The top of the image shows the part of the island that faces west. In face, the facility seen at the top of the image is called West Facility, one of the island's 10 separate jails.

| The moment the

judge bangs his gavel, the second leg of the race begins. When the

prisoner walks out of the courtroom, the accusatory instrument is

stamped by the Department of Correction and the clock starts ticking. It doesn’t matter if ten or ten thousand people are committed

that day, they’ve got twenty-four hours. “My staff can handle it,”

says Captain Fred Sporrer. But they’d have to bring in extra medical

workers, he admits. Correction has to accommodate whatever population is brought down to them, people in wheelchairs, people

with contagious diseases, people detoxing. And they have to make

absolutely sure that no adolescents [under 16] have mistakenly come into

their care.

The prisoner is taken to the New York City Department of

Correction Court Division, where they’re fingerprinted and given a

booking case number. Correction starts a form called a 239, which

will be used to classify the prisoner and decide where he will be

housed. From here they go to Intake.

A big fat packet of forms

associated with each inmate is brought to Intake and administrators

make sure they have everything they’re supposed to have. Instead of

a movement slip, they start a card to track every step and how long it

took.

|

Click the above image of 1903 fingerprints to learn how they figure in the Origins of the New York State Bureau of Identification or click the image below of 1913 fingerprints to learn how they figure in the ID bureau's origins. Each of the fingerprint images accesses its own web page of excerpts from Michael Harling's early history of that agency. At the bottom of each page is a access list of all the other pages in that presentation, The list page includes a link to a special special preface historian Harling wrote for this site's excerpts presentation, one of the very first featured when the site was launched circa 1999.

Like Stacy Horn, he too toured Hart Island back in the day when NYCHS-conducted history tours with photo-taking. Such tours no longer take place. See his photo album (a virtual tour). Use your browser's "back" button to return.

|

|

The prisoner is fingerprinted again, just in case a switch was made

and someone thought they’d get someone else to take their place in

prison. They’ll get photographed once more, and Correction will issue an ID card.

More paperwork is initiated that will end in visit

cards, phone cards, and an inmate account. Then the prisoner will

get a complete mental health screening. Is he suicidal? for instance.

This is followed by a complete medical screening, including blood

work. Does he have any contagious diseases or require any special

medical care? Then his security risk will be assessed and he’ll be

classified from 1 to 57, 1 being the lowest. Anything above 17 is con-

sidered high risk.

If they are a registered informant they may ask to

be separated from the general population. Correction will verify if

this is true and honor this request.

The security classifications are marked above the entrance to

each housing unit at the Tombs (they don’t say cell blocks anymore). Inside the doors are food warmers. Inmates are not taken to

great big cafeterias for meals like the old days. Too much potential

for trouble. Instead, they eat in their housing unit. Housing units

look like every other jail you’ve seen on TV An open area with a TV

surrounded by two levels of cells.

Prisoners will endure one more search before they are finally

housed. Inmates who are being held on homicide charges will now

be strip-searched. They’ll be instructed to remove their clothes, turn

around, squat, and lift their genitals. No physical contact takes place

during a strip search.

“But you can see if there’s anything up there.

Sometimes there’ll be a string hanging out so they can pull the stuff

out later,” Captain Sporrer explains. “Sometimes it just pops out

when they squat.” Cops do not like conducting strip searches and

some wince when describing it.

Most prisoners would prefer to remain at the Tombs. The work

here is less strenuous. It’s easier for friends and relatives to visit, and

the inmate doesn’t have to get up at 4:00 a.m. to get on a bus for

their court date.

It’s also safer because no one stays here long, so

dangerous cliques aren’t really given a chance to form. Everyone is

on their best behavior, hoping to stay. But space at the Tombs is

tight. If the prisoner was medically cleared, then like it or not, before twenty-four hours are up, he will be getting on a bus to Rikers

with anywhere from fifteen to seventy of his fellow inmates.

Within six days every [felony] is brought before a grand jury, who

will either decide that there is a case and indict, or they will decide

that there isn’t sufficient evidence and vote No True Bill (the prisoner won’t be charged).

From here on in there will be a series of pre-

trial motions, court appearances, conferences, hearings, followed by

a trial. If the prisoner is convicted, he will be sentenced, generally

within a month . . . .

Once sentenced, the prisoners are put back on a bus to Rikers. At

this point, the Department of Correction wants them out. The inmate is not their problem anymore, and they need the cell space.

|

The above Downstate Correction Facility aerial image appears on the web site of DiGeronimo PC. 12 Sunflower Avenue, Paramus, NJ, a leading NY region construction accountability firm. Click the above image to learn its role in the construction of Downstate Correction Facility. Use your browser's "back" button to return.

| They’ll be out of the city jail and into a state prison within a week.

(City holding facilities are called jails, the state facilities are called

prisons.)

They’ll be taken to the Downstate Reception Center opposite

Matewan State Hospital in Dutchess County, where they may spend

up to eight weeks getting classified once again. They’ll go through a

whole new set of screening and testing procedures to determine

their background, history of violence, health, and whether they

have any program needs (an academic program, for example). They

could be sent to one of seventy possible prisons, as their destination

is based on what’s learned during the classification process and what

space is available.

|

|