1886 banquet book excerpts detail Rikers & Hart USCTs formation. | ||

| ||

22 Years Later Union League Commemorates its Role in Epic EventBefore becoming major bases of NYC Correction operations, Rikers and Hart Islands were mustering-in and training bases for, among others, an estimated 4,000+ African-American soldiers during the Civil War. They served in New York State's three regiments of United States Colored Troops (USCT) -- the 20th, 26th and 31st -- whose formation was initiated and sponsored by the Union League Club of New York.

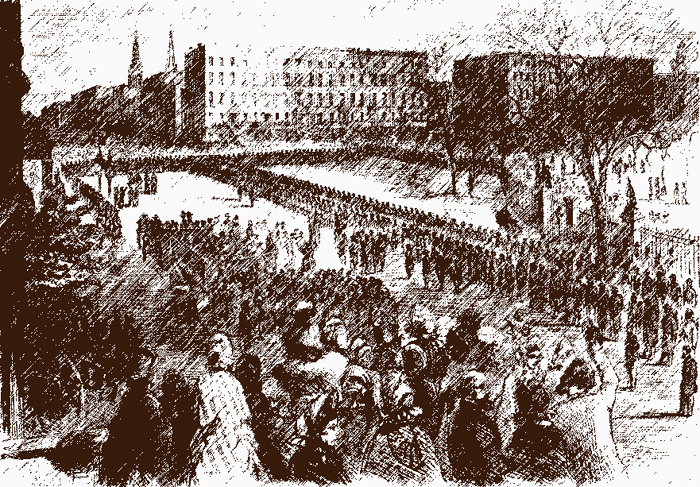

On March 5, that regiment was ferried from the island encampment to 34th St., Manhattan. The regiment first marched to the club's headquarters, then on 17th Street off Union Square, where the officers and troops received its battle flags. Afterward they marched in military formation down Broadway to Canal Street and from there to the Hudson River piers to their embarkation ship, the steamer Ericsson. Three hundred Union League Club members marched with them to the dock.

Participants were well aware of the historic significance of the ironic scene unfolding: Colored Troops parading to cheers from whites as well as non-whites lining the very streets where only nine months earlier blacks (and whites coming to their defense) were beaten to death or hanged from lampposts by mobs whose initial protests against the unfair draft law soon turned into racist savagery.

Twenty-two years later -- on March 16, 1886, to be exact -- about 70 Union League Club members from 1863 and 1864 and their guests gathered in the club's quarters, then at 5th Avenue and 39th Street, to commemorate their campaign to raise "colored regiments" for the Union cause despite resistance from the "peace Democrat" Governor Horatio Seymour and much of NY's power structure.

The Lincoln party leanings of club members come through loud and clear in the banquet book's recorded remarks. The League had George F. Nesbitt & Co., at Pearl and Fine Streets, in Lower Manhattan, regular printer of Republican broadsides and campaign materials, run off sufficient copies to distribute as souvenirs for the participants, for other members and for interested and sympathetic non-members as well as libraries and other educational institutions.

Fortunately, Google eBooks has digitalized a copy of this public domain book and made it available for non-commercial use. Using a downloaded Google-digitalized copy of the 142-page book, the New York Correction History web site has excerpted those sections most relevant to the start-up of the Rikers and Hart Island USCTs. A PDF file of this abridged version (34 pages) can be accessed by clicking the image of the excerpts edition cover (above left).

Reading These 19th Century Remarks With 21st Century EyesWEBMASTER NOTES: Readers should keep in mind that any lapses in 21st Century political and social sensibilities reflected by the remarks recorded in the banquet book may be accounted for by the fact the utterances came from 19th Century men celebrating an achievement accomplished some two decades earlier. In the wake of NYC's worse anti-black race riot, these men -- all abolitionists -- had overcome opposition and raised United States Colored Troops who marched down Broadway amid cheering crowds of well-wishing New Yorkers. No mean feat, certainly worth the regiments' sponsors recalling and celebrating with African Methodist Episcopal pastor W. B. Derrick, a Civil War Union Navy veteran, as their guest of honor.

The book excerpts are not presented as an example of how such a commemorative event should be structured and conducted but as source for details and insights into a significant chapter of Rikers and Hart Island history.

In contra-distinction to the word "negro" stands a different "n" word, one clearly pejorative, whether capitalized or not. This "n" word has prompted some educational authorities to remove Mark Twain's Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn books from student reading lists and school libraries. On excerpted Page 16 of the banquet book that offensive n-word appears twice, both times inside quotations which the speaker cites with obvious disapproval. In recounting resistance that he and Jackson S. Schultz encountered trying to enlist a military marching band to play in the planned 20th USCT parade, Col. Bliss attributed use of the pejorative "n" word to two well-known military band leaders of the period. The latter's reported negative utterances had made the club even more determined to secure a military band for the 20th's march down Broadway; and this the league did, obtaining one from Governors Island, as Col. Nelson B. Bartram relates on excerpted Pages 30 and 31.

Given that the offensive n-word was not quoted with approval but, on the contrary, used to illustrate the negativity which the league had to overcome in its raising and supporting the USCTs, I have reproduced the excerpted page as is. However, for those parents and teachers who may want to use the excerpted version of the banquet book with their children and students, for whom they feel the appearance of the original term might be an unproductive distressing distraction, I am working on crafting a version of excerpted Page 16 in which "n-----s" is substituted in the two places. To obtain a copy of this version, please email me at either address listed at the bottom of the home page.

Some modern day readers may find the fulsome praise for the Grand Old Party uttered by the African Methodist Episcopal pastor in front of this audience of Republican movers and shakers a bit hard to take.

If so, keep in mind that Lincoln's Party came to power in 1860 committed to ending expansion of slavery into new states, a stance the South saw as setting the stage for that institution's inevitable abolition. The Presidential candidate of Northern Democrats had favored letting new states decide slavery by popular vote. The Presidential candidate of Southern Democrats favored enacting a federal code to enshrine slavery's preservation.

When Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, "peace Democrats" such as NYC Mayor C. Godfrey Gunther found in it no cause for celebration. But for millions of slaves the carefully framed military order issued by Lincoln in his role as Commander in Chief became a sacred document freeing them at long last from bondage. Regardless of the limitations set forth in the proclamation's fine print, its sweeping effect was to tie the goal of preserving the Union to ending slavery. For the newly freed and generations of their kith and kin, Lincoln had been the new Moses, leading them out of bondage and they identified their liberation with his party.

Rev. Derrick's Republican effusions become easier to grasp when viewed in this context. If there be criticism of his GOP commitment on the general grounds that clergy ought not get so enmeshed in partisan politics, consider whether the same principle applies to current day high profile clerics heavily in involved in NYC Democratic Party politics. The observation is not criticism of their involvement, but offered to see Rev. Dr. Derrick's GOP involvement during the post-Civil War era from another perspective.

The banquet book itself contained no illustrations or photographs. The relevant images appearing on this web page were obtained during web research. Despite extensive web searching, no digital image of Rev. Dr. Derrick or his Sullivan Street church was found, though his name appears in sundry newspaper stories, books and various journals from that era. Nor did equally extensive web searching uncover an image of the 20th USCT chaplain, the Rev. George W. LeVere, or for that matter any other African American member of the regiment. If any reader comes across such an image, please contact the webmaster, using either email address at the bottom of the home page.

Other than Chaplain LeVere's, the unabridged 142-page banquet book, whose full title is Banquet given by the members of the Union League Club of 1863 and 1864 to commemorate the departure for the seat of war of the Twentieth Regiment of United States Colored Troops, raised by the club, contains no names of the African American members of the regiment. For that kind of information, visit the National Park Service web site: http://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm

|

home page |

USCTs |

Chaplains | Virtual Visit |

in USCT era |

20th USCT 1864 flags presentation sketched from different angle. | ||

| ||