|

Monday, June 5th, 1995, marked the 100th anniversary of the law mandating that New York City establish the Department of Correction as a separate agency.

Monday, June 5th, 1995, marked the 100th anniversary of the law mandating that New York City establish the Department of Correction as a separate agency.

On Wednesday, June 5th, 1895, in Albany, then-Governor Levi Morton signed into law Chapter 912 (of the statutes enacted at the 118th Session of the New York State Legislature). The legislation divided the city Department of Charities and Correction.

Chapter 912’s preamble described the law as:“an act to abolish the department of public charities and correction in the city of New York, and to provide for the establishment of two separate departments in place thereof, to be known respectively as ‘The department of public charities of the city of New York’ and ‘The department of correction of the city of New York,’ and to define the powers and duties of such departments.” Chapter 912’s preamble described the law as:“an act to abolish the department of public charities and correction in the city of New York, and to provide for the establishment of two separate departments in place thereof, to be known respectively as ‘The department of public charities of the city of New York’ and ‘The department of correction of the city of New York,’ and to define the powers and duties of such departments.”

It declared that the terms of office of the commissioners of the old combined department “cease and terminate on and after midnight of the 31st of December following passage hereof.”

In effect, it required the New York City mayor appoint a Correction Commissioner and three Public Charities Commissioners by Dec. 21, 1895, to assume those offices Jan. 1, 1896.

The term of office was set at six years until appointment and qualification of successors. The per annum salary for charity commissioners was set at $5,000, and for the correction commissioner, $7,500.

Chapter 912 gave the public charities department “charge of all hospitals, asylums, almshouses and other institutions belonging to the city or county of New York which are devoted to the care of the insane, the feebleminded, the sick, the infirm, and the destitute, except the hospital wards attached to the penitentiary and to other prisons and institutions under the direction of the department of correction.” Chapter 912 gave the public charities department “charge of all hospitals, asylums, almshouses and other institutions belonging to the city or county of New York which are devoted to the care of the insane, the feebleminded, the sick, the infirm, and the destitute, except the hospital wards attached to the penitentiary and to other prisons and institutions under the direction of the department of correction.”

The chapter gave the Correction Department commissioner “all the authority concerning the care, custody and disposition of all criminals and misde- meanants in the city and county of New York which the commissioners of public charities and correction now have ...

"He shall have the general charge and direction of all prisons and other institutions for the care and custody of criminals and misdemeanants which belong or shall belong to the city and county of New York.

"Said department shall be authorized to demand and receive all fines imposed for intoxication and disorderly conduct . . . “ "Said department shall be authorized to demand and receive all fines imposed for intoxication and disorderly conduct . . . “

The law authorized the Correction Commissioner to arrange to provide inmate labor for the service needs of the Charities Department institutions’ “grounds and buildings” but not “in any ward of any hospital.”

It required the city to devise a plan for dividing properties and personnel of the combined department between the two emerging departments:

“In such plan the city prisons, the penitentiary and the workhouse, with the grounds thereto appertaining, and the stone quarry on Blackwell’s island, and Riker’s island, shall be assigned to the department of correction.”

Among assignments to Public Charities were “the hospitals and asylums on Blackwell’s island, Ward’s island and Randall’s island, the branch lunatic asylum on Hart’s island and the farm at Central Islip, Long Island.” Among assignments to Public Charities were “the hospitals and asylums on Blackwell’s island, Ward’s island and Randall’s island, the branch lunatic asylum on Hart’s island and the farm at Central Islip, Long Island.”

Further sections of the chapter provided for the eventual realignment of island properties so that Blackwell’s island would become, in effect, more Charities Department territory while Rikers and Hart’s islands would become more Correction Department territory.

The governor who signed the DOC-creation bill into law 100 years ago was Levi Parsons Morton, who only two years earlier completed serving a term as U. S. Vice President.

In 1861, seven years after opening a dry goods business in the city, Morton founded an investment banking house that bore his name and helped keep the Union financially afloat during the Civil War and advanced U.S. postwar international trade interests.

He served in the U.S. House of Representatives (1879-81) and as U.S. minister to France (1881-85).

In 1888, Morton was elected Vice President on the Republican ticket headed by Benjamin Harrison against then-President Grover Cleveland, himself a former New York governor.

Cleveland had won the popular vote but lost in the Electoral College. Four years later he defeated Harrison.

Morton then returned to New York where in 1894 he was elected governor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

& APPRECIATIONS

The editor wishes to acknowledge help by the Municipal Archives . . .and Correction Academy. . . .

The Archives provided access to pictorial histories such as Notable New Yorkers of 1896-1899, by Moses King, 1899, N.Y.; The Brown Book: A Biographical Record of Public Officials of the City of New York for 1898-99, Martin B. Brown Co., N.Y., 1899, and the Kings Handbook of New York, circa 1899, also by Moses King, excellent sources for period photos of individuals and institutions.

Additionally the Archives provided access to such authoritative volumes as the History of the State of New York, by Columbia University Press, 1934 N.Y., and Four Famous New Yorkers: The Political Careers of Cleveland, Platt, Hill and Roosevelt, by Henry Holt & Co., 1923, N.Y.

The Academy made available old training manuals that contained useful information.

Other books used by the editor in gathering historical details included - New York by Gaslight, an 1882 guide by James D. McCabe Jr., published by Greenwich House, N.Y.;

- History of Tammany Hall by Gustavus Myers, by Dover Publications, 1901, N.Y.; The Good Old Days -- They Were Terrible by Otto L. Betterman, 1974, Random House;

- The WPA Guide to New York (of the 1930s), 1939, Pantheon Books, N.Y.;

- The Encyclopedia of American Crime, by Facts on File Inc., 1982, N.Y.

Queensborough Library filmed copies of 1895 New York Times issues provided relevant accounts concerning Chapter 912.

-- Thomas McCarthy, Editor

|

|

|

Mayor William L. Strong, who came to power as a Fusion candidate fielded in 1894 by reformers, fathered the emergence of Correction as a separate city agency.

A businessman nominally Republican, he ran with Democrat John W. Goff, corruption fighter, and named a former U.S. Civil Service Commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt, to steady the then scandal-rocked Police Department.

In his first annual message to the Common Council, submitted January 8th, 1895, shortly after taking office, Mayor Strong declared: “I am clearly of the opinion that the care of the indigent should be separate from the discipline of those who have broken the law. To continue these branches together prevents proper assistance to those incapable of self-support and prohibits the best results from being obtained from corrective discipline.” In his first annual message to the Common Council, submitted January 8th, 1895, shortly after taking office, Mayor Strong declared: “I am clearly of the opinion that the care of the indigent should be separate from the discipline of those who have broken the law. To continue these branches together prevents proper assistance to those incapable of self-support and prohibits the best results from being obtained from corrective discipline.”

With such mayoral encourage- ment, the state Legislature passed the agency division bill. In order for it to become law, city "acceptance" had to be communicated officially to Gov. Levi Morton, a prerequisite to the latter signing it into law. Since Mayor Strong had advocated, encouraged and supported the legislation, his formal approval was a foregone conclusion. With such mayoral encourage- ment, the state Legislature passed the agency division bill. In order for it to become law, city "acceptance" had to be communicated officially to Gov. Levi Morton, a prerequisite to the latter signing it into law. Since Mayor Strong had advocated, encouraged and supported the legislation, his formal approval was a foregone conclusion.

Nevertheless, on May 7, 1895, he conducted a hearing, as legally required, on whether the city wanted the legislation signed into law. After leading social reformers spoke in favor of approving the bill and no one spoke in opposition, the mayor declared: "I have given this bill a great deal of consideration and I am entirely in accord with its provisions. I shall, therefore, take great pleasure in approving the bill."

When on Dec. 21, 1895, in compliance with the new law's provisions, the mayor named the new commissioners of the separated agencies, he remarked that the management history of the combined agency had not been satisfactory but that he expected the new leadership of the new agencies would bring major improvement.

A few weeks later in his annual message, January 1896, he noted:

“On the first of this month the provisions of the statute passed at the last session of the Legislature went into effect, dividing the then existing Department of Charities and Correction into two separate departments, to be known as the Department of Public Charities and the Department of Correction. Provision was made for three Commissioners of Public Charities and for one Commissioner of Correction. These appointments have already been made.

“I am quite sure that our citizens generally do not appreciate the magnitude of the present departments referred to, or the work imposed upon the former Department of Charities and Correction. The management of the City Prisons, the care of the insane and paupers, and the care of the Penitentiary, together with the hospitals, covers already about 17,000 people, when originally not a quarter of that number was in contemplation.

“The condition of our City Prisons, to speak broadly, is execrable, and the accommodations in the Alms-house and Workhouse insufficient, inadequate and incomprehensible, while overcrowding is a startling characteristic of the penitentiary.

“The division of Charities and Correction and the increased appropriations for these departments is proper and necessary, and will, I believe, obviate many of the criticisms heretofore properly posed."

Splitting the Charities/Correction Department into two distinct agencies was among the reforms endorsed by a group known as the Committee of Seventy formed in Sept. 6, 1894, by many of the city’s leading citizens -- Democrats, United Laborites, and independents as well as Republicans -- meeting in Cooper Union.

Their choice of name was deliberately designed to evoke memories of an identically-named committee that had defeated “Boss” William M. Tweed’s Tammany Hall machine in 1871.

As in the earlier era, disclosures of institutionalized corruption in city government spurred the various anti-Tammany forces to put aside differences, this time to unite in battle against another  machine in the Tweed mold headed by a successor “Boss” -- Richard Croker, a former Fourth Ave. Tunnel youth gang leader. machine in the Tweed mold headed by a successor “Boss” -- Richard Croker, a former Fourth Ave. Tunnel youth gang leader.

On Sunday, March 13, 1892, the Rev. Charles H. Parkhurst, head of the Society for Prevention of Crime, preached a sermon at his Madison Square Presbyterian Church charging City Hall,  Tammany and the Police with protecting criminal elements. He backed up his accusatory rhetoric with sworn affidavits from private detectives he had hired and accompanied as they investigated the links between vice houses, station-houses and political clubhouses. Tammany and the Police with protecting criminal elements. He backed up his accusatory rhetoric with sworn affidavits from private detectives he had hired and accompanied as they investigated the links between vice houses, station-houses and political clubhouses.

The sermon and affidavits fired public indignation prompting a probe in the spring of 1894 by a state legislative committee. The vigorous and uncompromising efforts of its chief counsel,

Democrat attorney John Goff, uncovered systemic police and political corruption raking in more than $7 million annually and involving payoffs for promotions up the ranks. Goff eventually became Strong's running mate.

Among Mayor Strong's most important appointments was naming Theodore Roosevelt as Police Commissioner. Former Assemblyman Roosevelt, who served as U.S. Civil Service commissioner in President Harrison's administration, promoted the merit system approach within the Police Department as Commissioner.

For PDFs of all 4 pages of the 1995 NYC Correction Centennial issue, use table below to select paper size format to fit your printer capabilities.

For PDFs of all 4 pages of the 1995 NYC Correction Centennial issue, use table below to select paper size format to fit your printer capabilities.

|

|

On Jan.1, 1896, the Department of Correction began operating on its own, no longer joined to Public Charities. On Jan.1, 1896, the Department of Correction began operating on its own, no longer joined to Public Charities.

The initial inmate census on Jan. 1, 1896, was put at 2,650. That count was among the statistics contained in the Depart-ment’s first quarterly report to the Mayor, filed April 10th, 1896, and published in The City Record May 2, 1896.

Of the initial total, the Penitentiary and Workhouse on Blackwell’s Island (now known as Roosevelt Island) accounted for 2,009 inmates -- 1,049 in the Penitentiary and 960 in the Workhouse. The City Prison, also known as the Tombs, contributed 465 to the total with the remaining 176 coming from the five District Prisons. Of the initial total, the Penitentiary and Workhouse on Blackwell’s Island (now known as Roosevelt Island) accounted for 2,009 inmates -- 1,049 in the Penitentiary and 960 in the Workhouse. The City Prison, also known as the Tombs, contributed 465 to the total with the remaining 176 coming from the five District Prisons.

By the end of the quarter -- that is, on March 31, 1896 -- the total inmate population had risen by more than 10 percent to 2,926.

Much of the first quarterly report of the first DOC Commissioner, Robert J. Wright, was concerned -- as were subsequent reports -- with detailing the work done by inmates for the Department of Public Charities as well as for the Correction Department itself.

The number of things made or repaired and the number of days labor expended were recorded in precise detail, even down to the count of shrouds sewn. The number of things made or repaired and the number of days labor expended were recorded in precise detail, even down to the count of shrouds sewn.

The occupations listed include blacksmiths, tinsmiths, carpenters, painters, upholsterers, cot and broom makers, tailors, stone cutters, yard and coal workers, and outdoor laborers.

Wright itemized the number of inmate days of “ordinary labor” done for -- and in many cases, done at -- various city facilities “under the care and supervision of Keepers “ (the 19th Century term for Correction Officers). These included: Bellevue, City, Gouverneur, Randalls Island, Harlem, Infants, and Metropolitan Hospitals, the Insane Asylums, and Alms-house.

Other facilities where inmates worked under Keeper supervision included the Steamboat Department, the Storehouse, Stable, Bakery, City Cemetery, Gashouse, Fire Department, and the Branch Workhouse. Inmate labor gangs worked at various locations unloading coal and manure.

Mechanical labor, as distinguished from “ordinary labor,” also was detailed. Other facilities where inmates worked under Keeper supervision included the Steamboat Department, the Storehouse, Stable, Bakery, City Cemetery, Gashouse, Fire Department, and the Branch Workhouse. Inmate labor gangs worked at various locations unloading coal and manure.

Mechanical labor, as distinguished from “ordinary labor,” also was detailed.

For example: The Barge for Homeless Men, carpenters and painters; Almshouse, carpenters, painters, masons and bricklayers; Metropolitan Hospital, carpenters, masons, bricklayers and engineers.

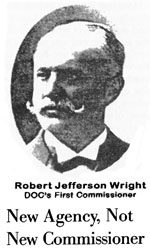

Under terms of Chapter 912 establishing the Correction Department, Mayor William L. Strong had until Dec. 21, 1895, to name his appointees to run the two emerging departments. He did so 11 A.M., Dec. 21, designating Robert J. Wright as Commissioner of Correction. Named Commissioners of Public Charities were John P. Faure, Retired Gen. James R. O'Beirne and Silas C. Croft.

Both Wright and Faure were Mayor Strong-appointees to the old combined Charities and Correction board and therefore already familiar with their departments' operations.

Commissioner Wright's background was that of business. He was a partner in the fertilizer firm of Kane & Wright. A staunch Republican, he had been first appointed by Mayor Strong in Spring 1895 to the old Public Charities and Correction board. Wright's appointment as DOC's first commissioner was fully expected because he was already familiar with its operation.

While Wright was DOC's first commissioner, his successor -- Francis J. Lantry -- was its first commissioner when New York changed from a one-county city to a multi-county city in 1898.

With Fusion forces divided in 1897, Tammany's candidate, City Court Judge Robert A. Van Wyck, won election as the first Mayor of Greater New York. Among Mayor Van Wyck's appointments Jan. 1, 1898, Lantry -- variously a butcher, a butchers union leader, and an Alderman -- was named Correction Commissioner. Lantry also was the Tammany leader in the 16th District where the new Mayor lived.

After scandals during the Van Wyck administration inspired anti-Tammany forces to unite again, Fusionists successfully fielded Columbia University president Seth Low as their mayoral candidate in 1901. He named Thomas W. Hynes to replace Lantry in 1902.

When Tammany's nominee, George B. McClellan, son of the famous Civil War general and Presidential candidate, defeated Low in the mayoralty of 1903, Francis J. Lantry was reappointed NYC Correction Commissioner Jan. 1, 1904. Thus he became the only city Correction Commissioner ever to serve twice.

The reasoning behind the reform splitting Public Charities and Correction focused on protecting poor patients from inmates.

Besides concerns about actual exploitation by inmates working in hospitals, the reformers were concerned that ill indigents were being stigmatized by association departmentally with accused and convicted criminals.

The agency division bill had emanated from the State Charities Aid Association whose leaders made clear their concerns at a hearing held by Mayor Strong Tuesday, May 7, 1895, in City Hall.

They noted the campaign for separation had begun a dozen years earlier with introduction of proprosed legislation and that reports by panels probing problems at the Ward's Island Insane Asylum called for just such a division.

Leading social reformer, Mrs. Charles Russell Lowell, said: "Unfortunate men, women and children who, through accident or disease, are thrown upon city charity, should be relieved from the stigma and contamination of association with criminals."

Prof. Charles F. Chandler pointed out that the bill did not go as far as reformers wanted in removing inmate work details from the charity institutions, but at least "it does not permit them to be employed as nurses in the hospital. Their employment has always been a crying evil."

Association official, Charles S. Fairchild noted that in all other cities in the state, jails and charitable institutions were operated separately, usually by sheriffs and superintendents of the poor.

Fellow association official Carl Schurz declared, "It's a sign of barbarism when jails and almshouses are thrown together under one management; the effort to separate them is a sign of civilization.'

|

|

|