IV:

The Reformation Movement

of the Late Nineteenth Century

Beginning soon after the Civil War, the Association was at the vanguard of the nationwide movement to understand the sources of crime and to overhaul and reform prison systems throughout the United States. Starting with modest efforts in 1866 to equalize the state and federal standards for commuting sentences based on good behavior, then moving on to an authoritative expose of the twin abuses of the contract labor system and the role of party politics in prison management, and culminating in the establishment of the Elmira Reformatory for first-time offenders in the 1870s, the Association was highly active in shaping the legislative agenda toward the treatment of prisoners. . . .

Time Off for Good Behavior

The New York Legislature embraced the concept of time off for good behavior in 1862, when it passed a law providing that a prisoner "may earn for himself a commutation or diminution of the term of his sentence" if he works diligently, obeys the rules, and "quietly submit[s] to the discipline of the prison." The formula established by the statute provided for one day of commutation for each month of good behavior and, once a record of six consecutive months of good behavior was established, two days of commutation for each month. All commutations would be forfeited if the inmate assaulted "his keeper or any foreman or convict, or otherwise endanger life, or by flagrant disregard of the rules of the prison."

|

The allowance for [NYS] good behavior was later modified to - two months of commutation for each of the first two years of the sentence,

- four months of commutation for each succeeding year through the fifth year, and

- five months of commutation for each remaining year.

An inmate who escaped or attempted to escape and an inmate "under sentence of imprisonment for the term of his natural life" were ineligible for any commutation. Section 152 of the Prison Laws (derived from Chapter 45 1, Laws of 1874, Section 12).

Fifty-first Annual Report -- 1895, pp. 231-232

|

The motivation behind the commutation policy was, simply, to create an "incentive to industry and obedience on the part of persons confined" to prison. In the course of its routine work of visiting prisons, the Association learned that more than five hundred inmates in the state's prisons who were serving sentences for federal crimes were ineligible for commutation because of the absence of any such federal policy.

The Association argued that New York's commutation policy had a beneficial effect on prisoner morale; conversely, the federal prisoners felt "unjustly and wrongfully punished" and the "subjects of a harsh adverse discrimination under the law. The just fear is, that, wanting the inducements to reformation which are held out so effectually to others, they will become reckless and indifferent to their own future, and the punishment designed in part for their good as well as the protection of the public, will not accomplish its proper ends."

The Association dispatched Dr. John Griscom, one of its vice presidents, to meet with President Andrew Johnson and plead for executive intervention and clemency. Dr. Griscom called on the President on Saturday morning, December 8, 1866. After a few minutes of discussion the President "expressed his concurrence ... and his strong sense of the propriety and value of the measure proposed. "

By five o'clock that afternoon Dr. Griscom was meeting with the Attorney General to help prepare an order for the President; over the weekend it was copied and presented for the President's signature on Monday morning. Under that executive order, the President extended to federal prisoners in New York State "the same clemency and abatement of time, upon the terms provided for the convicts under sentence of the courts of the State."

Seeking to expand the executive order to cover federal prisoners in all other states with commutation laws, in 1867 the Association lobbied for congressional action. Since no two states had the same commutation formula, the bill introduced in the United States Senate at the Association's behest provided that federal prisoners would receive whatever commutation benefits were available under the laws of the state in which they were imprisoned.

Having "received assurances from leading members of both houses that it would pass without difficulty," the Association's members left Washington. The bill that was ultimately enacted, however, "was very different from that framed and proposed by the Prison Association. It simply granted one month's diminution of sentence for each year."' The Association criticized this result, inasmuch as it caused all federal prisoners "to lie upon the same Procrustean bed" and would "create irritation, jealousy, and heart burnings, in the class which feels itself aggrieved," which would surely "lead to acts of insubordination and disobedience."

The Abuses of Contract Labor and Party Politics

The Tombs, circa 1871.

|

The Association's work has long been accomplished through consultation and advocacy with the Legislature and agencies responsible for administering the criminal justice system. This quiet influence was best demonstrated in 1865, when the Legislature established a special commission authorizing the Association to examine under oath any present or past prison officers "on all matters of fact and opinion, whereon they may think proper to examine them, touching the management of our prisons and the general subject of prison discipline and government."

The resulting report described in detail two horrendous abuses in the prison system: the contract system of prison labor and the influence of party politics on prison discipline.

Under the contract labor system, the warden rented out inmates to private contractors in various industries for a fixed daily sum. The prison provided factories for inmates to work in and keepers to guard them; the contractors provided raw materials and machinery. In theory the system was designed to alleviate the warden of the burden of managing both the prison's discipline and its industries. It was also thought of as a means of keeping the state from underselling private companies and from mismanaging a function it ostensibly knew nothing about.

Sing Sing sewing shop.

|

The realities of the contract labor system, as portrayed in the Association's landmark report, were quite different. The outside contractors would collude in setting low prices for the contracts; inmates were woefully underpaid, even under the terms of the bid; the state would regularly be cheated of its profits; and often the contractors claimed that they had lost money on a contract and then seek additional payments from the state. . . .

The biggest scandal arising from the contract labor system, however, was its impact on prison discipline. The contractors generally employed a class of persons . . . who would "introduce surreptitiously into the prison, forbidden wares, such as articles of food or spirits" and then engage in profiteering at inmates' expense. They would assist prisoners in escaping . . . In some instances the contractors would insist on a convict receiving punishment, while in other instances they would shield an inmate "from the punishment [warranted] . . . ."

The contract labor system also introduced the allure of money into the prison system, which resulted in bribery and corruption of the prison administration. Inmates could receive additional pay for extra hours of work, giving them the ability "to obtain abundant supplies of money, which they may use for personal gratification, or to bribe keepers to allow them to escape, or to bestow on inferior lawyers as an inducement to use an effort to obtain pardons." Not only was inmates' health at risk from overwork, so that they could be paid more, but the Association was concerned that their minds were being turned from any thoughts of reformation:

|

little good can be accomplished until the convict learns that the prison doors can only be opened by his own good conduct, as the result of law; until he is made aware that the same law which condemns him provides a method by which, through his own efforts, his sentence may be shortened; until he knows that while society takes the major part of his earnings as an equivalent for his support, it also bestows upon him a portion of them at the end of his imprisonment, so that he may, if he see fit, commence a career of usefulness, and, mayhap, honor. Report on State Prisons and Penitentiaries, pp. 196 -- 497. |

[Inmates work a quarry:

Making little ones out of big ones.]

|

While the Association's efforts were imbued with an optimism that reformation was possible, it also recognized that "it is quite possible, and indeed every way probable, that, while the great mass of prisoners would ... be reformed, there would be a residuum who would prove irreclaimable. Should this be the case, it would involve the necessity of a separate prison for incorrigibles, where they could be confined for life." . . . .

Equally pernicious as the contract labor system was the influence of party politics on prison discipline. State law provided that the prison system be administered by a three-person Board of Inspectors, which in turn appointed the wardens and other prison officials throughout the state. The inspectors were elected by popular vote for staggered three-year terms. "Whenever the majority of the Board is changed from one political party to another, it is the practice to remove nearly all the officers and to fill the vacancies with others who, in most cases, have no experience in prison management." . . .

|

In order to accomplish this [constitutional] reform the Association proposed that

- the administration of the various state prisons be centralized under the control of a board of prisons;

- that removal of wardens, keepers and other prison officials be only for reasons of cause; and

- that the members of the board of governors serve for ten-year terms and be appointees of the governor.

To be enacted these reforms first required an amendment to the state constitution. . . . Unfortunately, the new constitution incorporating these changes was rejected by voters in its entirety, although "no opposition to the prison article [has] developed in any quarter." Twenty-fifth Annual Report -- 1869, pp. 48-50.

An amendment was finally approved in 1876, providing for a single superintendent of state prisons appointed by the governor. New York State Constitution, Article V, Section 4 (1876).

The legislation promulgated thereunder provides that "no appointment shall be made in any of the State prisons ... on the grounds of political partisanship; but honesty, capacity and adaptation shall constitute the rule for appointments." Prison Laws, p. 271.

|

The long-term effect of the influence of party politics on the prison system was the absence of any competent, professional management. The Association observed how, over a twenty-five year period, political maneuverings had caused the administration of Sing Sing Prison to "oscillate between barbarity and humanity," as six different wardens held office and "the wise and foolish governors" alternated in power.

Three were "humane, forbearing, and just," with a personal interest in communicating with prisoners and thereby learning about planned escapes and riots by prisoners as well as overreaching and fraud by the contractors. The other three were advocates of inflicting "cruel and unusual punishments," and under their administrations "force and fear" were the rule of the day.

Inmates resented the "frequent and arbitrary" changes in rules and disciplinary enforcement brought about each time the keepers or warden were replaced. . . .

The Association fought to abolish the contract labor system and to remove the appointment of prison officers from the purview of politics. It urged an amendment to the state constitution to professionalize prison management and set forth a comprehensive plan of reformation to deal with the abuses of contract labor. The components included

- the establishment of different prisons for different classes of offenders;

- selection of competent prison officers; direct employment by the prison, not by outside contractors;

- a system of marks for good and bad behavior, under which inmates would earn commutation or increases in their sentences;

- educational and moral instruction;

- simple rules and the abolition of all cruel punishments and petty regulations;

- conditional pardons (probation, in today's parlance) to ensure continued good behavior until the expiration of the original sentence; and

- a system of supervision and aid for discharged prisoners.

The Sing Sing Riot of 1869 and

the Establishment of the Elmira Reformatory

Inmates on a work farm.

|

The years 1869 through 1877 were a watershed period for the Association. After twenty-five years of visiting prisons, organizing conferences on prison reform, issuing voluminous reports, ministering to discharged convicts by the thousands, and lobbying the New York State Legislature, the Association's calls for reform finally drew serious attention and tangible reforms.

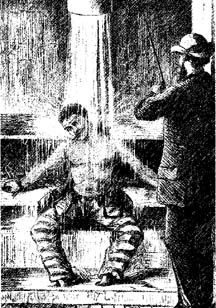

If one key event triggered the implementation of the reformation movement's agenda, it was the riot at Sing Sing Prison in late March 1869. The revolt, involving several hundred prisoners, arose in reaction to the death of a convict from the severe administration of a cold-water shower bath. Several convicts and one prison officer were killed in the insurrection, and the Legislature immediately began an investigation.

One consequence was "the enactment of a law prohibiting the further use of the shower-bath, buck and crucifix (sometimes called the yoke), as instruments or disciplinary punishment." The Association had urged the abolition of these punishments for years, and no doubt was instrumental in guiding the Legislature to finally take that initiative.

In its haste to act, however, the Legislature blundered and made the prohibition of those punishments effective immediately, with "no time ... allowed for the officers of the prisons to prepare for the change."

The result was further bedlam. Inmates in the state prisons became "turbulent and ungovernable, not infrequently assaulting officers with deadly weapons." The keepers felt that "some quick and sharp punishment was needed." To quell further disturbances, "a new mode of torture, called the hooks, was devised. . ." This torture involved locking an inmate's wrists in irons behind his back, raising his arms up and attaching them to hooks so that "the toes just touch the floor. . . ."

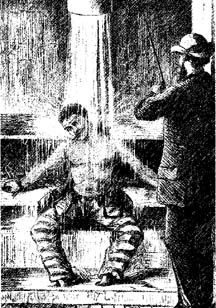

Shower bath at Sing Sing,

circa. 1869.

|

The Association's relationship with state prison officials sharply deteriorated as a result of the Sing Sing riot. . . . A conference was held between the state prison officials and the Association to discuss prison discipline, especially at Sing Sing Prison, but the distance between them was too great to bridge. The prison officials sought to obtain the Association's endorsement for the retention of harsh punishments in order to enforce discipline and deter escapes, while the Association members wanted to discuss fundamental reforms to the system. The Association declared: "Away with the ... lash, shower-bath, yoke, buck, hooks, and the whole array of degrading and torturing devices, in which the perverse ingenuity of man has been so fertile. Let them go to swell the rubbish of buried barbarisms."

. . . After the Sing Sing Prison riot a county judge in Westchester appointed a grand jury to conduct an inquiry into the causes. Its report presented three "propositions" for the riot:

- first, "the sweeping changes of officers with every change of political power";

- second, the abolition of certain punishments by the Legislature; and

- third, "the influence of the Prison Association [which] contributes to a false sympathy on the part of the community, which eventually results in the convicts being regarded as objects of sympathy and pity, rather than offenders against the peace and welfare of the community; and this, on coming to the knowledge of the prisoners ... causes a general discontent."

The accusation against the Association apparently backfired. "The press, with great unanimity, took up the defense of the Association and its labors, pouring its criticisms, at the same time, with merciless severity, upon the heads of the jurors. " [Twenty-second Annual Report -- 1866, pp. 344 - 345.]

Prisoner wearing a "Bishops Mitre,"

circa. 1874.

|

Riding the crest of public support, in 1869 the Association received an appropriation of $4,000 from the Legislature to help defray its costs. . . . in 1873 the Association became the beneficiary of one-half of the fines collected in New York County from violators of the state's anti-obscenity statute." The other half of those fines was originally designated for the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice . . . and later the Female Guardian Society.

Beginning in 1870, the New York State Legislature started to enact a series of laws aimed at creating a new model prison -- the State Reformatory at Elmira. Those laws provided for the construction of a new facility, to be populated by "male criminals, between the ages of sixteen and thirty, and not known to have previously sentence[d]" to prison. "The discipline to be observed in said prison shall be reformatory~ ... The contract system of labor shall not exist, in any form whatever, in said reformatory, but the prisoners shall be employed by the State."

The key elements of reform codified in the Elmira statutes closely mirror the reforms advocated by the Association for years:

- Judges would not fix the outer limit of the prison term of inmates sent to Elmira, although the total sentence served could not exceed the statutory maximum for the crime committed. This practice, known as indeterminate sentencing, was later codified in the criminal codes throughout the United States.

- The managers of the Elmira Reformatory were given the power to terminate an inmate's sentence, based on their assessment of his improvement. Toward this end, a system of marks or credits was established to reward or punish inmates, based on their behavior and progress toward reform. In effect, those managers became the nation's first extrajudicial authority with power to grant probation or parole.

- The managers were also given the power to parole inmates, subject to the power of revocation if an inmate violated the terms of his parole. The managers were empowered to release prisoners unconditionally "when it appears . . . that there is a strong or reasonable probability that [the] prisoner will live and remain at liberty without violating the law, and that his release is not incompatible with the welfare of society."

While a great era of prison reform was now dawning, the Association continued to lament that "the condition of the jails and penitentiaries is, with a very few exceptions, deplorably bad" and getting worse." Nowhere was this more evident than at the infamous Tombs, on Centre Street in Manhattan, which epitomized the terrible conditions of overcrowding and corruption pervading the entire prison system.

|

"The Tombs! where living men are buried, and, by a refinement of cruelty, the living are chained to the dying and the dead, until the whole becomes one mass of moral putrefaction...

The Tombs! whence those who were buried, issue forth again, speaking, and moving as men, and bearing the form of humanity; but with death,-- death spiritual and final -- with death stamped on their visages, and reigning in their souls. These are strong words, but they are not stronger than the truth requires." Twenty-seventh Annual Report - 1871. pp. 97-98. |

Fifty Years of Progress

|

Prison Laws, Section 145-146, p. 229 (derived from Laws of 1869, Chapter 869, Section 1) states:

"The punishments commonly known as the shower-bath, crucifix, or yoke and buck, are hereby abolished in all the State prisons and penitentiaries of this State."

The same also states [P. 230] that any prison official who violated this law would be guilty of a misdemeanor, punishable by a fine of $100 to $250, or by imprisonment of three months to one year, or both.

|

On the Association's fiftieth anniversary in 1894 it would reflect with satisfaction on the results of the Elmira Reformatory laws.

More than 4,700 prisoners had been released by that time on parole from Elmira, of whom 2130 were paroled to the care of the Association.

Emphasizing "reform and education of young offenders; and ... individual treatment of the prisoners, with release on parole as a reward of fitness and a test of character," the successes and failures of the Elmira reforms were the "objects of closest scrutiny" by the Association.

The Association concluded that "hundreds of men, once guilty of crime and imprisoned in the reformatory ... have come forth to occupy positions of honor and profit.

Many are fathers of families, some have attained wealth, nearly all have persisted in honest industry. "